E17

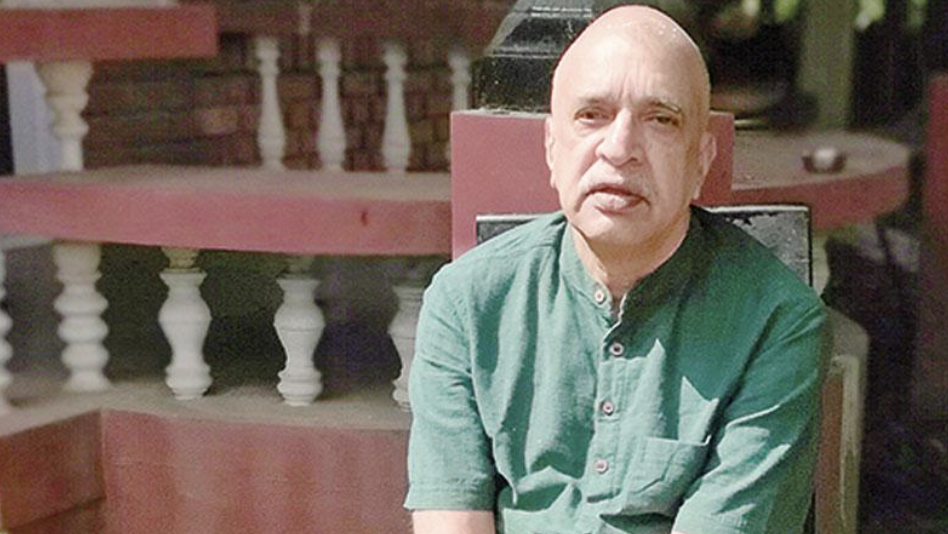

Dr Darshan Shankar: Traditional knowledge has contemporary relevance

Dr. Darshan Shankar is an educator, researcher and inspiration for young people. A pioneer in reimagining formal education systems, he has always advocated for building more multicultural institutional frameworks that can foster creativity and individuality for the people that enter it.

In this episode of Grassroots Nation, he is in conversation with A.V. Balasubramanian, a biologist and molecular biophysicist who founded the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems in Chennai, which works on sustainable agriculture. Having shared interests of science and traditional knowledge systems, Balu and Dr. Shankar’s association began in 1986, at a tribal village near Karjat.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Dr Darshan Shankar

Padmashri Dr. Darshan Shankar is the Chairman of the Indian Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, Managing Trustee of Foundation for Revitalisation of Local Health Traditions (FRLHT) & Founder Vice Chancellor of the Trans-Disciplinary University (TDU) in Bengaluru.

Born into a family of modern scientists, Dr. Shankar has always stood for innovation in education from a very young age. While working on problems of development and healthcare, his outlook throughout his career has been one for combining eastern traditional knowledge systems with western science.

He began his career in 1973 at the age of 23, from the University of Bombay, where he designed and implemented a postgraduate program based on ‘experiential learning’ that won the Commonwealth Award in 1976. He went on to work on issues of tribal development in forested tribal talukas of Maharashtra for the next twelve years and from 1985 to 1990, Dr. Shankar directed an all India Network of NGOs called Lok Swasthya Parampara Samvardhan Samiti (LSPSS) which is a network of individuals, groups and organizations working to revive indigenous systems of primary healthcare in India.

In 1993 he moved to Bengaluru, and with Sam Pitroda founded the FRLHT, TDU and a 100-bed healthcare research centre called the Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. For his contributions he’s won several national and international awards, such as the Normal Borlaug Award in 1998 for efforts in conservation of wild populations of medicinal plants, Columbia University’s Award in 2003 for revitalisation of traditional health-care systems in India, and was also conferred with the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 2011.

AV Balasubramanian

A.V. Balasubramanian is a biologist and molecular biophysicist who founded the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems in Chennai, which works on sustainable agriculture.

We need to create platforms for younger people… I started at 22, for people at that age we must start creating platforms where younger people can have an opportunity to spark, who have got something in them to do, they should have the opportunity to try out and test out. We don't have it today, we don't have those kinds of platforms. The formal education systems kill creativity in people, they make them conformists.

Dr Darshan Shankar

Additional Audio:

-

- Traditional Knowledge Digital Library – A collaborative effort by CSIR and the Ministry of Ayush

-

- I-AIM Healthcare Hospital! by I-AIM Healthcare

- Our customers recommend us to others for many reasons! | Listen why | I-AIM Healthcare Center by I-AIM Healthcare

TRANSCRIPT:

HOST

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

Dr. Darshan Shankar is the Chairman of the Indian Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, Managing Trustee of Foundation for Revitalisation of Local Health Traditions (FRLHT) & Founder Vice Chancellor of the Trans-Disciplinary University (TDU) in Bengaluru. He began his career in 1973 at the age of 23, from the University of Bombay, where he designed and implemented a postgraduate program based on ‘experiential learning’ that won the Commonwealth Award in 1976.

After working as a young faculty at the University of Bombay from 1973 to 1980, Dr. Shankar worked on issues of tribal development in forested tribal talukas of Maharashtra for the next twelve years.

From 1985 to 1990, Dr. Shankar directed an all India Network of NGOs called Lok Swasthya Parampara Samvardhan Samiti (LSPSS) which is a network of individuals, groups and organizations working to revive indigenous systems of primary healthcare in India. From 1986 to 1990, he also consulted with the office of the Advisor to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on the Technology Missions.

In 1993 he moved to Bengaluru, and with Sam Pitroda founded the FRLHT, TDU and a 100-bed healthcare research center called the Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine.

Born into a family of modern scientists, Dr. Shankar has always stood for innovation in education from a very young age. While working on problems of development and healthcare, his outlook throughout his career has been one for combining eastern traditional knowledge systems with western science.=

For his contributions he’s won several national and international awards, such as the Normal Borlaug Award in 1998 for efforts in conservation of wild populations of medicinal plants, Columbia University’s Award in 2003 for revitalisation of traditional health-care systems in India, and was also conferred with the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 2011.

He has also worked in the Planning Commission as Advisor of AYUSH, been a member of the National Wildlife Board and currently serves as a member of the National Biodiversity Authority at the Government of India.

Today Dr. Shankar is an educator, researcher and inspiration for young people. A pioneer in reimagining formal education systems, he has always advocated for building more multicultural institutional frameworks that can foster creativity and individuality for the people that enter it.

In this episode, he is in conversation with A.V. Balasubramanian, a biologist and molecular biophysicist who founded the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems in Chennai, which works on sustainable agriculture. Having shared interests of science and traditional knowledge systems, Balu and Dr. Shankar’s association began in 1986, at a tribal village near Karjat.

This conversation was recorded at the University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences and Technology in Bengaluru.

BALU

So, Darshan, this is a pleasant meeting for me. I recall one of the earliest meetings that we had was in the tribal village of Kashele, near Karjat, where you started your journey more than 40 years back. I had come to spend a few days with you. It’s been quite a long journey and you seem quite settled in this FRLHT TDU University and Hospital. But the reason why we are here today is that I’d like to request you to reflect on your journey – some of the things that you have seen, some of the things that you experienced, some of the things that you have reflected upon because we feel that this is of larger interest.

So to begin with, I know that you come from a family of modern scientists. Your father was a very distinguished scientist, a senior chemist in the atomic energy system, and many of your brothers went on to become surgeons and high place officials in private industry and so on. You grew up in Bombay, though I believe your ancestry and roots were in UP. Can you take us through the early years and tell us what your early influences were and what shaped your thinking early on?

DARSHAN

I’ve been doing what I’ve been doing, but I really haven’t reflected on why I’m doing what I’m doing. And so in a sense, this question is new for me and I’m responding more or less on the spur of the moment. One is that I have had a sort of a natural drive to do something, to do something useful, to do something that would be impactful. Many years before, when I was still in high school, I used to live in Bombay in a locality in which it so happened that in the building opposite to where I lived, I had heard from my friends about a person named Mr. Larsen, of Larsen and Toubro, the company. So I was maybe in 8th standard or something like that and I had no idea what the meaning of a big corporate like Larsen and Toubro. 8th standard. But I heard it’s a big company and this man is a, you know, a man of great achievement.

So one day I wrote a letter to him by hand in the back of a small notebook saying, “I’d like to meet you to discuss with you about your journey and how it is that you established such a big company like Larsen and Toubro. I’d like to have a chat with you about that.” And of course, a nutshell of that particular meeting was that he told me, “Look, there are no miracles, there are no shortcuts to doing anything big. It’s a lot of hard work, and nothing big happens overnight. It starts small and there’s a lot of grind and a lot of work, and then you can grow it, etc.”

The other thing that inspired me was my deep dissatisfaction with the education system. This whole story begins around the age of 21-22, when I had just graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Statistics from Elphinstone College of Bombay University. And my dissatisfaction was because I felt that the education system had not exposed me sufficiently to either nature, the world around me, the natural world around me, nor had it exposed me to society. I felt that my entire learning had happened in a very abstract, very abstract space, the abstract space of classrooms. A classroom is not nature, nor is classroom society, through reading books – again, for me, that’s very abstract, I would have preferred first hand exposure to… and maybe if you’re a student of science, etc, to laboratories which don’t also mimic or represent the complexity of life. They are also very abstract places.

So I felt that my education had not given me sufficient exposure to natural or social realities, and that was my dissatisfaction. What is this system of education that sort of keeps you… shuts out, you know, real life experiences?

BALU

Darshan, I see that you make light of this in the sense that there was no special influence, there’s no special drive. But to someone who observes it from a distance, I would say that you didn’t have a family or parents who were saying “Forget about reforming the whole country. First of all, you have to find a good job for yourself, you have to take care of your security, you have to take care of your family, think of that first.” You didn’t have people saying that. You also told me how, when you had an innovative idea about how different education could be, the first thing you did was to walk into the room of the Chancellor of Bombay University. Now, I studied in Central College, Bangalore, which has a very fine liberal atmosphere but if I saw the Principal at the other end of the corridor, my tendency would be to quickly get out of the way before he finds some problem with me and before he takes me to task. But you said you walked up to the office of the Chancellor and shared your ideas with him. So, anyway, you can please tell us how you went on to the next stage from there.

DARSHAN

Yes, I mean, that’s true that there were no pressures whatsoever from the family in the sense that my parents, and particularly my father, had no expectations from me. He was completely self reliant, self sufficient, not only from me, from all our other brothers, from his children. So, yes, I can imagine that if there were a family in which the parents were in some difficulty in debt or something like that, then thinking of children would be quite different. And my father’s advice to me was, “Just do whatever you like, but make yourself useful. Don’t be a burden on anybody.” So that’s true, that circumstance was very important.

This dissatisfaction with the education system, I thought to myself, or said to myself, “But what is it that I would like to do about it?” And I wrote initially half a page on one side of a small notebook, in those days, there used to be these small notebooks. I wrote my thoughts down on one side, saying that maybe in the university we should start a program. And since I had already graduated, a program for postgraduates on what I called experiential learning, wherein students would be from all disciplines, it was not for any particular discipline. All disciplines could be given the opportunity to get exposed to different facets of society, depending on their backgrounds, and challenged to do something.

I wrote my thoughts on this half a page and I said, “Now, who can help me to take this idea forward?” So I went to my Vice Chancellor to begin with, the vice chancellor of the university and I told him, “Look, I have this idea.” And he said, “Who are you?” I said, “I’ve just graduated.” He said, “Don’t waste my time. There’s nothing that you can do, you’ve just graduated out and I have too many other things to bother about.” So he just dismissed me. That didn’t stop me. The next thing I did was try to meet the Chancellor of the University. You know, the Governor of a State is also supposed to be the Chancellor of a University. This was Bombay University, the Chancellor at that time was a great educationist and statesman by the name of Nawab Ali Yavar Jung. I’m talking of 1972-73.

BALU

This actually brings me to another facet of your personality, which I sometimes try to reflect on. As you say, many people, teenagers or even past that, they survive with dreams but then opportunities present themselves, and if you have to translate those dreams you have to go to the next level. You have to challenge yourself, rise to that. Most people, or a large number of people back off at that stage, they say that they are not able to take that leap. I think it was some poet who made a statement that there are two great tragedies in life – one is not to have your prayers answered, the other is to have your prayers answered. Now somebody gives you an opportunity and you take it and move on, or do you back off?

Now, one part of the Darshan Shankar journey which I found very fascinating was that he started this informal type of real life education experiment in Bombay University. And a short time after that a businessman came and presented him with an opportunity saying, “Look, if we really are real about real life education, don’t do it in the middle of Bombay city, why don’t you go to a forested area where there’s an opportunity.” Can you tell us about that? I’m quite fascinated to hear that aspect, how opportunity presented itself and how that helped you to move on to the next stage.

DARSHAN

This person, Ali Yavar Jung, must have been very exceptional, I mean, I saw him in his capacity as a Chancellor, but he must have been a very exceptional person to encourage the way he did, for me, a young person of 22. So when I met him, I again gave him that small half piece of paper that I had written. He read it carefully, he said, “It’s a very good idea, this business of experiential learning program. To connect universities to nature, to connect university students to society.” But he said “Look, you can’t execute it on the basis of an idea like this, you need to convert this into an implementable proposal.” That’s the language he used. And I looked at him and I said, “Sir, I don’t know what is the meaning of a proposal”, because I had not written any proposals. So I said, “I don’t even know what a proposal means. And while I’m very serious about wanting to do this, I need some help to understand what does it mean to actually write a proposal.” So he smiled and he said, “Alright, I will connect you to two people who are great educationists.” So one of them was a person by the name of V.M. Dandekar, those who may have a background in economics or something like that, the history of Indian economics might have heard of a person named V.M. Dandeker. He was at that time the Director of a School of Economics and Politics that was based in Pune. He was the first author of a book on poverty in India, and the first book on measuring poverty in India was written by V. M. Dandekar. So he was very well known in social science circles. He said, “Go and see V.M. Dandekar.” And he said, “After you have met him perhaps you should also meet another person,” whose name was J.P. Naik.

Now J.P. Naik, those who know the history of education in India and not perhaps very many people would know it, J.P. Naik is the person who founded institutions that still work today like the NCERT – the National Council for Education Research, the Indian Council of Social Science Research, the Council for Historical Research. And so he laid the foundations, J.P. Naik, for both school and university education in India. Ali Yavar Jung advised me to meet both these people. So I said “Fine, I’ll meet them.” And he said, “I will write to both of them, you know, just to introduce you and then you follow up,” and so on.

And he did so. So I wrote to J.P. Naik and Dandekar. So Professor Dandekar said to me, you know, “Why don’t you come to Puna?” So I said, “Sir, but before that I’d like to meet you when you are next in Bombay,” because that’s where I lived. And the reason I said that to him is that I had no money to go to Puna, to go and see him in Puna. I didn’t want to, you know, take any money from my father. So I wrote to him saying, “Look, let me know when you’re next in Bombay, I’ll meet you.” So I met him not very long later when he came to Bombay to give a lecture somewhere. Briefly I told him what was in my mind. He said, “Look, you need to come to Puna and spend some time with me, maybe two or three weeks, three weeks would be good.” So then I looked up at him and told him candidly, I said, “Sir, I have no financial means to come to Puna. On top of that you are asking me to stay for three weeks. I certainly don’t have resources to hang around for three weeks. Where would I stay?” And he said, “Don’t worry about it.” He opened his purse, gave me 50 rupees, he said, “Buy a ticket and come and once you come there, then I’ll look after your stay and everything in the institute.” So again, to cut a story short, I did develop a proposal under his guidance in three weeks time. He was a very strict person and I had help from the faculty of that particular Institute of Economics and Politics.

And four weeks later I had similarly, at a little later date, also met JP Naik. But I didn’t rely on J.P. I sent him that proposal for his views and comments which he gave and I incorporated those that I thought were useful, etc. And very soon, I mean maybe five weeks after all this, I went and met my Chancellor again and said, “Here is now the proposal.” He looked at it and was very pleased that a half piece of a paper had been converted into an implementable proposal and he said, “Okay, now the ball is in my court.” Maybe a week later – all these things moved very fast because all this happened between the age of 22 and 23… Yes, a little before that, he said to me, “How do you know that with this proposal, there will be students interested?” Because the proposal was essentially to give fellowships to students to spend two years living in rural areas in different contexts, depending on their backgrounds, their disciplinary backgrounds, get exposed to the reality there and do something in response to the problems that they saw on the ground with guidance from university faculty. That was the sort of proposal in a nutshell, fellowships for this kind of student, that is what the experiential learning program was about.

He said, “How do you know there will be anyone interested in these programs? What if there is no one interested?” So I said, “Just give me a little time.” And I had a network with NGOs in the state. Through someone I knew, I widened that network and I literally went to every single town in Maharashtra where there were universities and people going to graduate from different disciplines – be they art, science, engineering, medicine, agriculture, so on, so forth. And I must have spent the next three months in 15-20-30 meetings that were organized with the network. And I would go there and speak to people and say, “Look, what are you people planning to do post graduation? There’s a scheme that we are trying to develop in the University of Bombay which will give you scholarships if you have the courage to go out and live for two years in a rural area and address challenges which will be different in these different locations.” And I had created posters and so on and so forth explaining this scheme saying, “Take two years off and learn,” that was the poster. I put it up everywhere, in all these places. And so when I came back three months later to the Chancellor, I had 500 applications which I informed him about. So he said, “This guy is serious about it.” So he was now very pleased. He said, “Now the ball is in my court and we’ll see what can be done.”

And a few days later, he called me – he was like that, he would personally call. And he said, “Look, I want you in Raj Bhavan at 8 o’clock in the morning.” No further information. I landed up at 8 o’clock on the said date. He met me. He said, “Look, there’s a car going to the airport to pick up the Union Education Minister. His name is Nurul Hasan.” This was Indira Gandhi’s time, Nurul Hasan was her Education Minister, also a historian, a scholar and an educationist. So I said, “Fine.” He said, “He’s going to be very busy the moment he touches the city. The reason I’m putting you in this car is this car will go right up to the tarmac of the aircraft and this guy will get down. He will have no option but to talk to you on the way back and you’ve got 45 minutes time. That’s it. The moment he touches Raj Bhavan, he is tied up in a whole lot of meetings. So you have 45 minutes to convince him about your idea. I am not going to come, I am not going to tell him anything. That’s up to you. All I can do, which I have done, is I have given you the opportunity to talk to him by putting you in this car.” So I said, “Fine.”

We had a very heated discussion but I managed to convince Nurul Hasan. And he said, “Fine, you know, I’ll call you to Delhi to meet the education secretary.” And thus that program got funded by the Union Government as an innovative program in university education – an experiential learning program in Bombay University mooted by a student because I was only 22, turning 23 and with scholarships and all this sort of a thing, whatever the scheme envisaged. And that’s how that particular program began. So that is the way I was able to make the first step in my dissatisfaction, about university education not exposing people to society, to the natural environment through this sort of a program. And in that program we had students from agriculture, from medicine, from social sciences, even from the performing arts. So that was stage one.

And then I executed that program for about seven years or so. It won an international award from the Commonwealth as being the best program in the entire Commonwealth for linking university education to community needs and so on and so forth.

But seven years later, Ali Yavar Jung passed away. He used to just keep a watch on this, he was interested. The university administration tolerated this program because it was not the usual kind of a classroom oriented program. And seven years later, after he died, there were people within that university who said, “What’s this funny thing going on in the university? It’ll disrupt our well organized system of…” And there were no examinations in that… There was only a thesis, an action oriented thesis. So they said, “Let’s put an end to this program or convert it into a more respectable program.” And so at the end of seven years, the Vice Chancellor at that time, somebody else, called me and he said, “Look, we are going to call this a program in rural development Masters. Only six months or so will be fieldwork, the rest will be classroom. There will be papers, examinations and all the normal stuff. The only thing is that we will allow six months of fieldwork.” At that point I put in my papers and resigned from the university. I said, “This will destroy the whole spirit of the program.”

So post leaving this university I met this industrialist who was the owner of a company called the Pest Control of India. It’s a well known pest control kind of a company, maybe a 500 crore turnover or something like that. But the owner was a philanthropist so he called for me and he said, “I’ve read about this university program, it looks very interesting. Can you spend one weekend with me?” And that weekend he took me to a tribal area close to Bombay, a place called Karjat. But the tribal block, not near the railway station, it’s a railway station as well. And he said, “I have 40 acres of land here. Why don’t you tell the university that I will donate this land to the university for this program that I read – this experiential learning program – you can create a campus here.”

I was at that point just leaving the university, I had almost put in my papers. I had put in my papers. So I told him, I said, “But still maybe the university will be interested.” So I went and spoke to the Vice Chancellor and other authorities, and they said, “We are not interested. It will be a liability because 40 acres of land and looking after it and all, we are not interested.” So I came back to him and I said, “They’re not interested.” He said, “Are you interested?” Because he knew I was leaving, and I said, “Yes, this would be good. I will establish something here.” And that’s how I moved on to the next stage of the journey outside of the university. I was literally kind of thrown out of the university because they thought that what I was doing was not relevant to the modalities of a good university.

BALU

The reason why I think this is important is when I first visited Darshan Shankar, I was wondering how on earth the previous night I had spent in his parents’ place – they were in this enclave of atomic energy officers where, this is where Darshan had grown up. And then the next morning, I traversed deep to a tribal area where he was in a tribal hut. Subsequently, his wife has delivered children there, attended to by a tribal dayi. So it’s not a distant theatrical exercise that he was indulging in. Very often I see sometimes people start up with an idea that seems revolutionary and at some point there’s a chance it becomes stable, but reduce it to a kind of a tokenism, saying, “There is a course, but six months you go to a rural area and then come back and write a paper on it”, and there could be a different kind of a chance to transform it and take it to a different level. So I found it quite fascinating that he pursued his idea. Otherwise he could have maybe joined the university in some sort of rural development department and retired now as a professor of rural development, or something equivalent to that, I presume.

But then he planted himself in the Karjat tribal area and the next part of the journey is the more fascinating part to me, where I encountered him because of my interest in traditional knowledge. And one of the things that I heard from you, Darshan, is the first experience that you had of traditional knowledge, soaking in the tribal people’s knowledge regarding ecology, environment, medicine. And what I think is a really seminal turning point, as I see in your life, your meeting with Vaidya Ramesh Nanal, who gave you an entire perspective on Indian knowledge, can you please tell us about that?

DARSHAN

Yeah, I stayed for twelve years in this tribal area and we more or less continued the similar kind of work, but not on a university platform, but in an NGO platform where young people would still be encouraged to apply themselves to solve problems. I had colleagues from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai, who joined me in Karjat. They took a sabbatical from the IIT and helped me there. It was an NGO, it’s not important the name of it, but it was in this place that I got a deeper exposure to plant based knowledge or traditional knowledge, both relating to ecology and largely relating to health.

I was walking one day in a village and somebody met me, a tribal person whom I knew, of course, and he said, “Look, can you help me? I have got a swollen testicle.” The testicle had swollen to double, more or less double the size. So I had a look at it, I’m not a doctor or anything, but I could see that there is a problem there. So I said, “I’ll find out, you know, the nearest doctor who could help you in the closest town and see what can be done.” And as I was talking to him, we passed by another tribal young person, who was a healer, a traditional healer in that area. And he heard the conversation and he said, “Don’t waste your time for such a simple problem to go to a doctor.” So I looked at him and I said, “What do you think we should do?” He went and plucked the leaf of a plant. Now that I have been exposed over the years to medicinal plants of this country, I could rattle off the name of the plant, the botanical name, calatropus gigantia and it had a local name – ark – is the local name and it’s growing everywhere. It grows wild all over the place, very common plant. So he took a leaf of the plant and he said, “Just put a little whatever cooking oil you have and a little of turmeric and wrap it around the testicle and change it every day.” They used to wear traditional, what they call langoti in Marathi. He said, “Change it every day, and in four days it should be back to normal.” Sure enough, in four days it is back to normal. I was very impressed, and I said,

“Look, this looked to be a very difficult condition. In fact, I found out that in modern medicine, you call that hydrocele.” Hydrocele means when water fills up in the testicles for some reason, physiological imbalance. A hydrocele is a semi surgical condition in modern medicine, you can’t treat it in the way… So I was very impressed.

And when I wanted to find out more about the medicinal properties of this plant, I went to my friends in the university departments in IITs, and I said, “Do you know this plant?” They said, “Yeah, botanically we know.” “Do you know the medicinal property?” They said, “No, we don’t know, that’s too complicated to find that out.” So I said, “Somebody should know because the tribals know this. Not just this, 500 other species.” So they said, “We don’t study in modern science or modern medicine, chemistry of wild plants and their uses and all this stuff.”

So that was the first time I heard about Ayurveda because, you know, I have a background in statistics, nothing to do with plants or medicine. So I went to the best ayurvedic physician I could hear about in Pune and asked him, “Do you know this plant?” He said, “Of course we know the plant. The plant is called in our literature, ayurvedic literature, it’s called arka, a r k a, arka.” And he said, “The meaning of arka, it’s a sanskrit word which has been given to this plant is the sun.” Just like the sun is so hot that it can evaporate water bodies, so any disease which is related to water filling up in some part of the body, and in this case it was a testicle, but it could have been the abdomen – there is a disease called ascites where water fills up in the abdomen and then you have to really, in modern medicine, you have to pull it out by inserting a large needle and like pull it out, the water. So again, it’s a semi surgical operation. But if you simply tie the leaves of this plant around your waist or in this case that I narrated around the testicles, within a few days those leaves have that property that they will absorb that water and it will come back to normal.

Then I learned that there are textbooks on what is called in modern science, ‘The Pharmacology of Plants’, that is the properties of plants. There are textbooks on preparation of medicines, and mind you, the Government of India has recently, not recently, but like over the last exactly 20 years actually, the Government of India, the Central Council of Scientific Industrial Research, CSIR, if you look up Google, you will see something called the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library, for short TKDL, you can search TKDL, you will see 20 years of work of the Government of India CSIR, where they have documented plus three lakh herbal formulations from ayurvedic literature with their properties and uses.

Professor Mashelkar, who used to be very famous… spearheaded this along with a Secretary in the Ministry of Health named Shailaja Chandra. And over the last 20 years, I mean last when I heard about it, they had reached cross three lakh formulations. This is a very large number of herbal formulations. Now you may not realize by listening to me how large this number is, but the total number of drugs, synthetic drugs in the world market is estimated to be of the order of 4000. So what is 4000 versus three lakh formulations with their properties and uses? That’s what it is.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO – TKDL by CSIR – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iy1X7Oqnfy0&t=60s

So I gathered as I began to encounter the knowledge of Ayurveda that there is a pharmacology, pharmacology is about the properties of plants. There’s a pharmaceutical kind of knowledge, which has got three lakh formulations. There are textbooks on diagnoses, there’s textbooks on treatment. Today you can walk around this university and go across the road, there is a hundred bed hospital that Mr. Ratan Tata set up for us. And 50,000 people come every year to this hospital and are treated with these formulations. And they must be working because the hospital gets no grants. It was set up by Ratan Tata, but gets no grants from the government or anybody else. If they don’t work, no one will come. People pay, of course, we cross subsidize in the sense that when Mr. Tata supported this hospital, the trustees of the Tata Trust told me, “Look, you can also borrow from bank. You are taking a gift from us, a philanthropy from us. So what is it that you’re going to do? Will you give free treatment to your customers? Because we are gifting you the whole hospital,” and they spent 25 crores building this hospital. So I said, “I’m willing to do that for free but, you know, there are 150 people who will be working there, doctors, nurses, therapists, drugs, all this. Are you going to support me indefinitely to pay their salaries?” He said, “No.” Then I said, “You do this thing that I will not turn away any customer because he has no money but let me take money from those who can pay. Then I’ll cross subsidize.” And that’s how we run the hospital. We don’t turn away a single customer on account of economic status.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO – iAIM HOSPITAL – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ilo15VYZGhQ

Now, in the earlier part of the story, Ramesh Nanal, a physician who I consider to be the person who really enlightened me and illuminated my understanding about traditional knowledge, because this was a physician, a very well known physician, and a very successful physician in Mumbai, Ramesh Nanal. He was amongst the first people I met when I encountered tribal knowledge. Ramesh Nanal spent five years in Karjat, not full time, he was a practitioner, very busy, but one day in a week, he would drive down at his own cost and come to this tribal area and meet with local healers. For five years he did this one day a week, that means four times in a month, you know, so, I mean, we are hugely indebted. This whole movement now, what we started in Karjat spread to NGO’s all over India. There was a whole network of organizations, because this is not only a Karjat phenomena.

You go to Ladakh and Spiti and you will find the same phenomena. There will be healers, I’m talking of community based healers who know the local flora, who know the uses of flora and they are the last mile reach for the village household. North, south, east, west, you go to the desert in Rajasthan, you go to trans-Himalayas, you go to the northeast, wherever you go this tradition exists. Over the years, from the Karjat days, I got exposed to both this community based tradition and scholarship and the knowledge of the physicians of Ayurveda. There are two facets of our heritage that I discovered from that Karajat experience – one facet is an oral tradition known to communities. They are the carriers of this oral tradition, like that calotropis plant. He doesn’t know which text or this or that and he’s not bothered about it either but he knows the use and he uses it. And we now have a database here in the university where I can show you 6500 species known to the communities of India, like calotropis, different species, not one, 6500. It’s an enormous number of species, it’s almost one third of the entire flora of India. That’s the number of species that communities know and use.

And then you have this other tradition that TKDL is all about, where there are 20,000 medical manuscripts on all branches of medicine and surgery which has got very deep, sophisticated knowledge of plants and their properties and their uses and diagnoses and treatment and surgery and medicine. So that is what that small exposure to Karjat led me to, you know, over the years.

BALU

Infact, for the first time, I realized visiting and interacting and hearing people like Darshan, how some of these scientific practices are deeply enmeshed with some cultural practices and values. For example, in Karjat, all the tribal physicians had a custom that once a year, around the time of Deepavali, they would see and touch and thank every single medicinal plant that is used by them for treatment. As I understand it, it’s like a community based biodiversity assessment. Every year you see, are the plants still there? Where are they? Do you have to walk longer distances? Are they less dense, more dense? Are there new species coming up? It’s like an assessment.

And even this name that he said… Infact, Professor Ms. Swaminathan once made an interesting remark, saying, tribal taxonomy is value added taxonomy. It’s not like a modern taxonomy where you just have a latin name. For example, tribals may call a plant by the name hadjoda or hadjodi, which means haddi jodne wali, that which is used in bone setting and so on.

So one of the next steps of the journey, which I consider important, is the parent organization that he formed – Academy of Development Science. He first reached out and networked with some other like-minded organizations in Maharashtra and from then on, he went to launch an all-India network that’s called Lok Swasthya Parampara Samarthan Samiti literally translates into an all-India network for people’s health traditions. I think that is what helped him to go to the next step, and subsequent steps, which are very important, because the way in which he got ideas, knowledge, everything about this tradition, traditional medicine deep into the policy framework, hardware, software, everything with the Government of India, the education system, the system, the Planning Commission. So maybe you could tell us a little bit about your thinking with respect to LSPSS. It got funded by the government of India through CAPART.

So one of the very interesting programs was his fellowship program by which graduates of Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha from colleges can go to the community and study for one year, two years, three years with the traditional bone setter, traditional Netrachikitsa, Vaidya, etc . So I recognize LSPSS as a very important step and that, in a sense, led to an opportunity for an all-India exposure, thanks to his first meeting with Mr. Sam Pitroda, at the insistence of Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, the young Prime Minister who wanted to have an interaction with NGO’s from across India.

DARSHAN

At my time, when I was 22, my contemporaries were thinking different directions, but like me, about social transformation. Amongst them were people like Bunker Roy. I knew him quite well as a young person. His wife, Aruna, they were very, very different people then from…. They have matured and grown and done a tremendous amount of very interesting work. But I knew them at the start of the journey. And there were other people like Dhunu Roy, an engineer from IIT. Even people like Ravi Chopra, who was interested in water and hydrology and environment and so on, so forth. All these were, you know, contemporaries and we used to meet a little bit and we knew each other, but we were all busy in our own things.

So when Rajiv Gandhi became the Prime Minister of India, it so happened that Bunker Roy was his classmate, somewhere, I think in Doon school or something like that. And so he told Rajiv Gandhi, the newly appointed Prime Minister, that, “Look, you shouldn’t only be consulting mainstream people about development in India. Why are you only taking consulting from bureaucrats? Why are you taking it only from mainstream institutions? What about non mainstream institutions? What about NGOs? Can the Prime Minister of India give some time to such people who are on the ground?” They’re not people sitting in classrooms or here or there, they’re working on the ground in so many different locations, in so many different fields.

Rajiv Gandhi must have been a very open minded person and he said, “Why not?” A Prime Minister is a busy person so he allocated 150 minutes on a particular day. 30 NGO’s from all over India, which included Bunker Roy himself and several others, were, I don’t know by what process, selected to speak before Rajiv Gandhi and expose him to this NGO perspective on India’s development. I happen to be one of them. Now, the letter we received for that particular meeting, said that 30 people, 30 different organizations and different dimensions, the prime minister has very limited time. So it’s going to be five minutes only per organization per person. Five minutes, whatever you want to say, five minutes sharp, not a minute more. So that was the challenge. And of course, during the meeting, there were bureaucrats around to listen and so on and so forth. So I use my five minutes sharp only to press home the point that traditional knowledge has contemporary relevance based on my work. That was the message I wanted to convey in that five minutes.

I know I succeeded because after hearing 150 minutes of presentations (5 x 30), the Prime Minister spoke for about 20 minutes, to say what he gathered from what he had heard. But in that 20 minutes summary that he made, he did mention that, “I recognize the importance of traditional knowledge, I think it’s a good point.” I was the only one making that particular point, so I knew that I had been heard. And during tea, also in the brief interaction with him, he said, “Yeah, yeah, you know, this is important. We must do something about it.” And the bureaucracy was listening. That’s how I got invited to another meeting very soon later, that particular thing. So I was not known to the top bureaucracy or whatever, to another meeting where at that point, Sam Pitroda was Rajiv’s right hand man.

You might, you might or might not know, you all may have been too young at that point of time, the Technology Missions were launched – that was the one big highlight of Rajiv Gandhi’s work. Huge Technology Missions for Literacy, a Technology Mission on Oilseeds, on Telecommunication on Health – five missions launched. One of them was on Health. So as a result of my getting into this network of bureaucrats or whatever that power network was that Rajiv Gandhi represented, and so my name got recorded because of that meeting. I got invited for this health brainstorming of Sam Pitroda’s on the National Health Mission.

Sam addressed that particular mission, and he said, “Look, we must do something about basic health in this country, and our priority is immunization. There are so many things to be done, but immunization can save lives, etc., particularly lives of children and so on, so forth. And so our mission will largely focus on immunization of children”, not on dozens of other things that, you know, healthcare needs to do. And he was addressing different sections of society. So I got invited into a meeting where he was addressing NGOs and saying, “I want your cooperation for this National Health Mission.” So I was one of the guys who was invited, and I got up during that meeting and spoke to Mr. Pitroda, and I said, “Mr. Pitroda, this is a National Mission, is it not?” That was just a rhetorical question. And I said, “Why is it that you are not looking at any inputs coming from traditional health science?” He was puzzled, he said, “What are you talking about? No one has ever told me anything about traditional health science, what’s that?” But he was open minded enough not to brush me aside. He just said, “Look, meet me after this meeting, I want to know more about this.” So that’s how I met Sam. I’m talking of 1986, now we are in 2023. Sam Pitroda happens to be… I have had an association with him ever since, and he happens to be the Chancellor of this University as well. And so we have a very, very long association, ‘86 to ‘22.

BALU

But the part that I found interesting, how this opened the door to larger things was when Mr. Pitroda said, what is the role that traditional medicine can play in immune preventable diseases for which the national strategy was vaccination. What Darshan was pointing out is that if you want traditional medicine scholars to be part of something like this, it makes no sense to involve them just like paramedics saying that you also deliver these vaccines, you also give these injections. So what should we do?

We can ask them, what is your idea of building immunity to disease? And they come up with the whole theory saying that we have the idea of Vyadikshamatva, how to build resistance to disease. So that led to a very interesting meeting where for three days in Ahmedabad, there was a national level consultation with about 60 people flown in from all over the country. The top pediatricians, modern physicians from all India Institute of Medical Science, top institutions, National Institute of Immunology were there. So were the top Ayurveda Siddha physicians from Jamnagar, Ahmedabad, Kerala, Kottakkal were for the first time, perhaps, talking and listening to each other as equals, not just saying that we have the solutions and we want you people to deliver this respectfully, listening to them at whatever your ideas about disease, immunization. And when Mr. Pitroda came to inaugurate the conference and heard that, something had flipped or something had changed, he realized, but he had a predisposition to that, actually. Subsequently we learnt that Mr. Pitroda himself has said that he was one among eight siblings who was delivered in a tribal village in Orissa, I think? He said his mother delivered the children in a village where there was no electricity, no flowing water. All the children survived and done well so, “she must have done something right,” is the way he used to put it.

DARSHAN

He was delivered at home. And assisted by a traditional midwife, no doctors, etcetera.

BALU

So he had to be reminded of this. But then he felt that this is something that needs serious attention. This cannot be a bits and pieces thing that is add-on to an institution that’s already running, which eventually led to the formation of what today is FRLHT which is Foundation for Revitalization of Local Health Traditions. But what I consider very important in this is how, rather than being very marginal or hardly being noticed, this gets into the agenda of mainstream thinking at a very senior level. That I think is one of the important institutional contributions that has been made here. Subsequently, it also has created a situation where he was able to interact at a very high level with the government, the bureaucracy, the corporates. And he also had a stint of a few years with the Planning Commission as Advisor of Ayush. I believe that that’s also an important formative stage in terms of influencing thinking and policy. Can you tell us a bit about that?

DARSHAN

Yeah, I mean, the interaction with Sam Pitroda represented so called modernity. And he was being exposed through me to the idea that traditional knowledge is contemporary, contemporary meaning that it’s not something obsolete, it is something which has modern applications. He was getting exposed to the idea that this whole notion of tradition and modernity as being two polar opposites is rubbish, they are just two different knowledge systems. And if they begin to talk to each other, then something innovative can emerge. Otherwise, traditional knowledge is brushed aside as being ancient, old, obsolete, irrelevant, and only diehard people with some ridiculous ideological leanings that are also there, associated with traditional knowledge, no doubt about that. There are lots of people who embrace traditional knowledge because of some ideology. But here we were not talking about the relevance or the contemporary relevance on the basis of any ideology of any kind. We were talking about it in terms of contemporary relevance, what can it do today and tomorrow? How can it take India forward? How can it improve the quality of healthcare? That was the perspective.

So starting with 1986, under the National Technology Missions, the Mission sponsored a meeting between modern immunologists, the best in the country, and traditional physicians also from all over the country. And the whole dialogue was around immunization or immunity and the notions of immunity, the strategies of immunity. And of course, as you know, the modern strategy of immunization, which we also saw in COVID that there is a vaccine, there are vaccines for various conditions which are supposed to build in you the antigens to fight against various conditions – that is a particular strategy for doing immunization. Without going too much deeper into that, except to say that there is no doubt that vaccines have a certain mode of action in terms of antibody antigen and so on, so forth, they are universally accepted. There are a few controversies around vaccines and how long they are effective or sometimes adverse effects that arise and so on, so forth, but those are controversies. The basic science underlying antibody antigen etc., is fairly well established and accepted. But the question now is that if you think, or if generally knowledge systems or people involved with knowledge think that there is only one way in which you can achieve immunity – in this case through vaccines and so on and so forth – then that may not be something that everyone can agree to, or at least from the perspective of the work I have been doing, it is not something that I would agree to.

Take a biology laboratory. We know there is no biology laboratory in the world, whether it be in Cambridge, or Harvard, or Bangalore or China, or anywhere that can mimic the complexity of biological life. The way we study biology in laboratories, we only study it in experimental models, which do not mimic the complexity – the complexity of life is you know, there are trillions of cells in, say, the human body, trillions. And they are talking to each other. If you want to do an experiment on any aspect of the biological system, you need a model which has captured all those trillions of cells. And there is no model of any biological model which can show you all those trillions of cells at the same time in one so-called model. I’m saying the entire enterprise of science is therefore labeled as reductionist, meaning it gives you a reduced view, it gives you a partial view, it gives you an incomplete view.

Now traditional knowledge in India does not adopt the method of European science to understand nature. In science, when we look at nature, the method broadly that we adopt is what I would call the observer-observed method. The observer is the scientist, the observed is nature. So you separate the observer from the observed. Now, we know for a fact that you are also, we, the observer, are also part of the observed, because we are part of nature, we are not apart from it. Yet the method we use to observe nature is as if we were apart. The laboratory is a representation, symbolically of the separateness, because you are observing something under a microscope or something, but you are observing it with that modality of separating yourself, whether it be biology, whether it be chemistry, whether it be physics, whether it be astrophysics. Now, in Indian knowledge systems, we do not separate the observer from the observed. We have methods of observation based on what is called Sankhya, where the observer and observed are not separate.

Suffice it to say that what we discover by our methods, which are not the European methods, the test of a knowledge system is – is it functional? Otherwise, there’s no use talking about it. So as long as a system is consistently functional, that is the test of a system, okay, as long as you can learn its principles anywhere in the world.

So we work, for example, in this university on memory and cognition. It’s a huge problem. As you age, if your memory begins to deteriorate, then Alzheimer’s, dementia, all this sort of stuff comes in. Now we are managing neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s, dementia, Parkinson’s, strokes with no molecular medicine. We are treating them with herbal formulations of the kind that the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library has computerized, you know, those kinds of things. And if people are not getting relief, they won’t come. But we treat hundreds of cases of Parkinson’s, of strokes, neurological, autism of children and so on, so forth. Everything that medicine needs to deal with except emergencies, we are no good at that, ayurveda is no good at that. Advanced surgeries? No.

But the moment you see it working, then you have to go deeper and see what are its principles, what are its concepts, and that dialogue must begin. And therefore, the best place is universities, the best place is knowledge institutions. We must have multicultural knowledge institutions. My observation is we don’t have a sufficient number of multicultural knowledge institutions in China, in Japan, in India, in Africa, and there’s no use having institutions based on ideology they don’t take you anywhere, there’s no substance in that.

I’ve been to China a couple of times, I’ve been to Japan. I’ve been to a few countries in Asia, Thailand, etc., and I’ve been to Africa, I’ve been to South America. And everywhere there is this problem that their indigenous knowledge traditions are being suppressed, oppressed, destroyed. Sometimes they struggle against this in an ideological way and I don’t think that is the way. We have to create knowledge institutions.

Institutions, you know, you don’t want speeches from people about this and that. You want institutions where you can demonstrate the value saying, does ayurveda improve cognition? Can ayurveda improve glucose metabolism? Can ayurveda design plant proteins that can improve health? Can ayurveda give a solution to malnutrition? Can it solve the problem of anemia that this country has got so many people suffering from based on its concepts, its principles, and the experience is, yes.

BALU

So, looking back, what would you say have been your major learnings on the path that you have taken and if there are any things in terms of what you would or what you could have done differently, if there’s such a thing. Other thing is looking ahead, what are your hopes, what are your fears, what are your dreams that you think are not achieved? And if somebody today is setting out on the path that you have trodden, what would be your advice?

DARSHAN

Broadly I would start off by saying that we need to create platforms for younger people… I started at 22, for people at that age we must start creating platforms where younger people can have an opportunity to spark, who have got something in them to do, they should have the opportunity to try out and test out. We don’t have it today, we don’t have those kinds of platforms. The formal education systems kill creativity in people, they make them conformists.

I was involved in a program in the university, I was involved in the program in Karjat where young people were given opportunities and looking back, what I would say is that while they did explore applications of their knowledge or creativity, it was not enough. Just like in startups, you give them seed capital. Today the model of a startup is you come to test your idea, do a proof of concept, then you’re given a little seed capital to start. You’re not on scratch. It’s very tough to do it from scratch. I mean, this institution and my entire journey has in some sense been scratch. There has been no one, I mean, we have struggled to get and we have got support, but there was no institutional mechanism to, say, a young guy like him, “Look, we’ll give you 50 lakhs a year for three years to test out your idea.”

No, there’s no such platform available. So looking back, in all the young people that I have worked with, etc., I think they would be much better off if there was not only the opportunity first to explore, but there was also some kind of a social entrepreneurship fund. Not indefinite because they don’t want that indefinite, they are doing things on their own, but something for the next three years will back you up then that helps you get grounded. So if I were to design programs of that kind again, I would attempt to do something like that.

Recently there has been an announcement of a National Research Fund, NRF. So there’s going to be a very large fund for research. I think the newspapers talk of it in terms of 5000 or 50,000 crores, I’m not sure. Very large sum for encouraging research in university systems, etc.. Very, very large fund. I think this is a very welcome thing to create such a fund. But I think that such kinds of resources should be used and applied also for multicultural proposals which combine knowledge from different cultures. If it were, say, in medicine, then I would say, “Here we work on the interface between ayurveda and biology. We have set up labs where Ayurveda has a role, key role, but modern biology also has a key role.” But there are not enough people who will support a program on Ayurveda Biology.

I run a hospital which is called Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. There’s not enough support for so-called Integrative Medicine. At best I can bring in some modern diagnostics to monitor someone before and after but I don’t have resources to hire people who would be from different medical streams, working under one roof and taking collective decisions, or taking decisions by a certain scheme of shared responsibilities and so on and so forth. Ideally, I would like this hospital to be one roof under which I can do surgery which will not be done by ayurvedic people.

Today one of the reasons why my footfalls will not grow to the level of a well-established modern hospital is that they’ll say they can’t do any surgery here. For surgery, I have to go there. If under one roof you provide the best of surgery and medicine and different systems, etc., then integrative medicine will flourish. But now it’s so inconvenient. When I can’t get any relief elsewhere, then my last resort is to come to a place like this. Not my first resort. Why do we make it so difficult for people?

So I think that these kinds of platforms of research funds should be used to support multicultural initiatives. And I say multicultural, not in a, you know, faddish way or an ideological way. It’s because there is no single knowledge system which has the solutions and understanding or complete understanding of anything.

BALU

My observation is that specifically in terms of integrative medicine, in a more nuts and bolts way, he can say how it is making a difference because the hospital is one of the flagship efforts, there may be other such efforts that you should…

DARSHAN

In the university, we work on three dimensions of integrative health science and practice. The three dimensions are – one is clinical practice, which is in the hospital. The second dimension is research, in which we tackle and look at problems in an integrative way. And the third dimension is education in which we offer the only educational program in the country and perhaps in the world, because we offer the only integrative education program in an MSc degree in Life Sciences, but focused on the interface between ayurveda and biology. It has a combination of the two, and one can do a whole Master’s degree. So that is an educational dimension of integrative health science and practice.

In research, we use the approaches of modern nutrition and ayurveda nutrition to design plant proteins. Making plant proteins is well known, but the challenge in plant proteins is how do you make them bio assimilable? There’s no use eating a protein which doesn’t get properly assimilated. The assimilation principles we derive from ayurveda, so we use an integrative approach in designing future foods, like, plant protein is a future food because we want the world to be moving out of animal proteins because of climate change effects in breeding animals all over the world. I mean, today, so much percentage, a very, very high percentage of land all over the world is put to raising animals instead of food crops and plant foods, unproportionately high. This is known. So the shift to plant proteins is important. I mean, we raise animals but to make plant proteins bioavailable, bioassimilable, that’s where we bring in ayurvedic knowledge.

So in research, we work on glucose metabolism. Now, that may sound, but it’s a very key thing in your entire body’s homeostasis depends on how you metabolize glucose. If you don’t metabolize it well, you can get problems with things like diabetes and all that. The starting is proper metabolization of glucose. Now, we study glucose metabolism in an integrative way. So we have a laboratory here where we study them at a genetic level, we study them on cell lines and so on, so forth. But the interventions that we are designing are based on a combination of products or herbs from ayurveda, which we study in modern ways. And that is showing us much deeper insight into how to deal with glucose metabolism. We have designed a food just made from amla, you know, nelli and curry leaves that we use in cooking and drumstick leaves and a few spices. By spices, I don’t mean chilis, I mean things like ginger or piper longum, the round, the long pepper, not the round pepper. And we have converted it… We have labs here and processing technology here where we have converted it into a very tasty chip. So instead of eating a potato chip, you can eat this kind of a chip, crispy thing, and you have four of them and your iron absorption for the day is done through food. You don’t need an iron supplement because you’ve got karipatta and moringa and all, which have got iron content in them. So we are developing foods… So there is research going on, on the integrative platform.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO – PATIENT TESTIMONIAL OF i-AIM HEALTH CENTRE – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sBb1iDoPPQ

In the hospital there are conditions which we treat in an integrative way. We treat cancers where complementary meaning combined, integrative, that means you have wounds coming up in the mouth because of radiation or because of strong chemotherapy, ulcers and all, and there’s no way they know how to solve them. They come here and get treated and so on, so forth in many conditions.

Or sometimes, like in the case of strokes, if someone gets a stroke and there are two kinds of strokes, but the one stroke more common is the ischemic stroke. In the first four hours, there are clots that are there, and it’s only in the first four hours that allopathy has a fantastic drug which can dissolve those clots. If they don’t get dissolved, the damage is long term. But post that, a stroke is a stroke, and post that 4 hours, even if that clot goes away, you may find that the patient is not able to speak properly, some side is paralyzed, and so on. Then our treatments are much, much better in recovering speech and recovering the paralysis, the rehabilitation so to say, the physiotherapy is better done here.

Take even bones. I’m talking of bones, meaning, of course, things like osteoporosis, things like rheumatoid arthritis, but even broken bones. Now, the entire theory of managing broken bones in general, whether in the spine or anywhere else, is that in Ayurveda, we say the healing of the subject who’s had this broken limb or bone, wherever, the healing does not end with the healing of the fracture. If you go to a good surgeon, he’ll just align the broken part to its original place – that’s called reduction, and it’ll heal. If you don’t align it, it will heal badly. Ayurveda says the healing doesn’t end with the realignment and the healing of that broken bone, because the impact of that bone disturbs the entire, shakes up the entire physiological system and unless that is also corrected, the doshas which are imbalanced, if they are not corrected, then you will keep suffering.

So there are many examples of integrative medicine in practice, that is clinical practice. Research will take on a completely new, I mean, a broader dimension. In a nutshell, I have to resort to the philosophical framework, meaning, in research when you look at, say, diabetes, the allopath says, “Diabetes? Elevated blood sugar and here is a drug to reduce blood sugar.” But diabetes is glucose metabolism at fault, symptom is elevated blood sugar, the cause is glucose metabolism. If you don’t deal with correcting glucose metabolism and only deal with correcting that part of it, then that’s an incomplete, that’s just fixing a symptom, it’s not fixing the underlying cause that is responsible for that. So in research, when we do and we combine, the research workers combine people from these two knowledge systems, we get better drugs, development, design, better understanding of mechanisms, better understanding of food.

We are now working on a very bold program which we need resources for, which is for mass scale personalization of food. Now, you know that, you should know at least that it’s rubbish to tell anybody that this ketone diet or this low carb diet is good for everybody. It’s complete rubbish. At the frontiers of food and nutrition, globally, we say each one of us is unique, genetically unique, etc., and so the solution has to be unique. That is what is called personalized medicine. It’s not a fad. It is because the variation is so much that you need personalization. Today, we are trying to achieve personalization through wearables, so you have now wearables which can monitor 20 different parameters – your blood pressure, your glucose, post-eating food, what is called postprandial etc., but they don’t add up… So they give you personalized information about you but if you put all that data together and say, “Now, what should I do in terms of food and nutrition?” You don’t get an answer.

So we are working on a program where we are building databases which combine properties of food from modern medicine or from food chemistry – protein, carbohydrate, fat, that is chemistry of food. Chemistry of food is not the same thing as nutrition. Even if you know the chemistry of a food, how you will absorb it will be different from… depends on you. You, meaning on your metabolism, on your unique genotype. Because you are not consuming this or you are deficient? No, it’s very complex. The biology of food is important. And what we are given advice by dietitians is only on the chemistry of food saying, “You’re not eating enough protein,” or something. But which protein to take, which will suit me? It all depends on my metabolism, the bioenergetic, its much more complex. So we are working where we are combining integratively the understanding of nutrition from ayurveda, the understanding of nutrition from biology, the understanding of properties. We’re building databases and algorithms and trying to use artificial intelligence. And finally, for the user, an app where you just say, “Is this meal going to suit me or not?” And it will tell you, “Minus this, add this,” or this or that or whatever. That means to make it mass, I must make it available to you. But for that, you need back end databases to do that. And those backend databases. And that’s a program that can impact the whole world, is interested in personalized nutrition, but today only the rich are trying to get that through wearables where they still don’t get the complete answer.

Now, if you can use AI and use these backend data databases, even the poorest of the poor can get personalized nutrition. So it’s a program we are working on, maybe three years, four years from now, we should be able to roll out some parts of it. But all this is integrative. Not just one thing will not work because ayurveda knows whole but doesn’t know part. Modern medicine knows part but does not know whole. Ideally you want to combine the two. That is what integrative is about, whether it is in the hospital, whether it is in the lab, or whether it is teaching students whole and part in the MSc program. These are three dimensions of integrative…

BALU

What I find very interesting is that despite the fact that he is on about 50 years of a solid track record, he is still thinking of the next ten years and where this institution would go. And in terms of integrative medicine, I think it’s very hopeful because as a civilization we had not just tremendous diversity and tolerance, but also eclectic traditions and a genius for synthesis – this is perhaps the most fertile ground you’ll find anywhere in the world for nurturing integrative medicine. So thank you for sharing all your reflections and good wishes for your future efforts, Darshan, we take leave with that.

DARSHAN

Thank you, Balu, for forcing me to reflect in a way which I don’t normally have the opportunity to do.

HOST

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode.

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.