A few months back, we received an internal letter from the founder of an NGO, reflecting on the relationship between funders and founders in the development sector. An anecdote about impact leaped out, in which the community was asked what had changed as a result of the organization’s intervention. The founder had expected the community to talk about the NGO’s flagship program—targeted at improving livelihoods and income—but in village after village, the community partners explained that, “The fear has gone. We are no longer afraid.”

How does one measure fear or its absence? How does one measure something priceless?

The story provoked us to consider what assumptions might be constraining how we think about impact. Compared with domains like manufacturing, in which the relationship between inputs and outputs is relatively direct and causal, ascertaining the impact of social programs is tricky (which makes it all the more important to learn from our partners). After all, societal problems exist within systems, which are not static but inherently reflexive: The very act of intervention changes the system, which, in turn, requires interventions to change. However, development sector measurement and evaluation approaches often don’t reflect this reality: Most often evaluations are sequenced to come in at the end of a program, as opposed to evolving with the program. Implementation to evaluation is usually a straight line, while social change work goes in cycles. And evaluations typically focus on metrics without fully appreciating the second or third order effects a change in those metrics might have on adjacent variables.

This is why traditional evaluation (in which expert judges determine the value of an intervention) is giving way—as Emily Gates described at a recent webinar hosted by CECAN—to a new thinking, in which the evaluator is a co-learner who is developing value. As Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP) has gotten more interested in trying to best understand and articulate the impact (and learning) of all our grants, we started asking our partners to share how they see the impact of their work. How did they think a philanthropy should judge its own performance?

Our partners work in many different fields—climate action, biodiversity and conservation, gender, civic engagement, justice, media, and youth engagement among others—and across rural, urban, and tribal geographies, with annual operating budgets ranging from $50,000 to $10-15 million and with teams both lean and large. By taking feedback—via an online survey—from this broad range of organizations, we tried to get a comprehensive sense of what the sector as a whole thinks and needs.

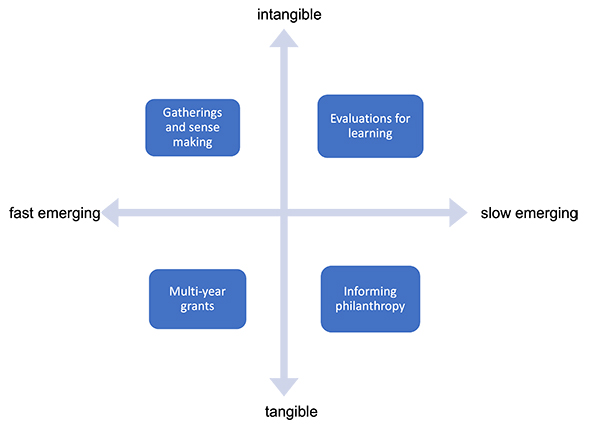

When we started to analyze the impact data that around 80 organizations shared with us, we realized that in reporting results as “impact,” our partners were making a variety of unstated assumptions, as well as treating certain other things as axiomatic. To make sense of it all, we took a step back and broke down what lay underneath. After first reading and discussing all the feedback that came in—and writing a reflection note to get our own thoughts and reactions down—we worked to categorize our grantee processes, outputs, and outcomes by Engagement, Collaborations, Concrete Actions, and Policy Change, after which two broad axes began to emerge, as the framework below plots:

Impact is a spectrum: Along the Y-axis, efforts that result in clear policy change are considered tangible outcomes, while the ecosystem collaborations an NGO would forge—in order to get to the policy change—are taken to be intangible. By the same token, the X-axis plots the results reported by NGOs across a continuum of fast and slow emerging, from quick wins to, well, slower wins. Countable actions like vaccinations or children enrolled would be plotted under concrete actions, whereas any progress made towards shifting policies or increasing the network of actors that care about the NGO’s cause come under results that are slowly emerging.

What became clear from sorting through the data was that most organizations (if not all) operate in all four quadrants at once, and there is no hierarchy of actions or results. Concrete results are no less important or “strategic” than policy pushes: “Countable” results add tangible value to individuals who are being supported on the ground. Field actions also birth insight and innovation that eventually makes it to policy. In the same way, while engagement—under which we have results like “number of report downloads,” “number of website/video views,” and “frequency with which a network convenes”—can feel ephemeral, consistent engagement is a desirable fast emerging pre-requisite for longer-term deeper collaboration (which is plotted under slow emerging).

For example, one of our partners in the justice space undertakes concrete actions, providing free legal aid to children in conflict with the law. However, they also collaborate with network organizations that interface with children around other issues; they drive engagement around their work through a series of online and offline outreach events and collaterals (and by engaging volunteers); and, finally, owing to the trust, relationships, and insights built in the field, they are in a position to advocate for reforms to the Juvenile Justice Act (reforms that stand to impact many thousands of children).

Given the two axes exist as continuums, and an organization’s work slides up and down and side to side along these axes, it is centrally important to look at how metrics and indicators speak to one another across the breadth of the organization’s work, instead of focusing on a single isolated metric.

Defining Distinct Forms of Impact

- Concrete Actions: Most nonprofits have a “community” they work with, such that activities done for/with the community can be captured as metrics of progress and impact. However, NGOs often feel the pressure to scale their work—either geographically or tactically (through partnerships or policy change)—out of a desire to see systemic change rather than “unit level” change. Many leaders, therefore, find it difficult to strike the balance between being strategic (through fundraising, building the organization, pushing partnerships, and driving advocacy), and connection to the original cause that brought them into the sector in the first place. Concrete actions are important because working alongside the community and its people is rewarding in a relational way that cannot be substituted. Tangible unit-level actions have, and will always be, central to social work because that is where the joy and conscience of this work lies.

- Engagement: Partners typically report engagement metrics as a sign of progress, assuming that increasing interest, awareness, and engagement bodes well for the mission. Be it website analytics, report downloads, likes/hits on digital content, increase in the size of a network, increase in the frequency of interactions between members of a network, and other similar indicators, most organizations see engagement with the larger ecosystem (or with the general public) as desirable. However, depending on the organization’s goals, lesser (but repeat) engagement can be preferable than lots of one-time use/engagement (or vice versa!). In the for-profit universe, payment is a good proxy for demand or a person’s interest in a product or idea. But in the nonprofit world, where products/services are not measured in terms of payment, should stakeholder buy-in be instead measured in terms of how much time, effort, or social capital stakeholders expend?

- Collaborations: Partnerships emerged as the hardest impact metric to define. Organizations reported collaborations and partnerships as positive results, but they frequently defined collaboration very differently. For some it was numeric—more members in a network, more participants on a platform, more collaborators, or the launching of more collectives—while others talked about convergence of efforts by different organizations towards the same goal. When it came to asking why partnerships and collaboration are necessary, the thing we heard the most was that the scale of the problem was too large to be taken on by any one organization. Collaborations bring diverse approaches into the mix, building a critical mass, or collective action. But while this rationale is often taken as an axiom—even while recognizing the difficulty of collectives truly collaborating—networks often end up competing, and partnerships can remain superficial and capricious (versus congruent and stable).

- Policy Change: Some nonprofits focus a lot more on policy change, a hard-won, but highly valued result. Understandably, policy change affects millions of people and opens up the space for social sector organizations to support the implementation of the new policy, making it a favored goal. At the same time, many organizations see themselves as allies and partners to other anchor organizations, who are taking on policy change. Nevertheless, the relationship between field implementation and policy and advocacy can be tightly linked, and organizational focus can shift between one or the other (or include both). Philanthropies too locate themselves in different ways when it comes to influencing policy. Analysis of our own partner data showed us that we tend to favor supporting organizations that aspire to or are playing the role of systems convenors.

How Might a Philanthropy Gauge Its Own Impact?

Across 80 organizations, certain points came up again and again, and as we sought to reimagine what makes for impactful action, we developed four broad ways forward that linked different forms of impact, which we mapped to the original impact quadrant.

- Enable CSOs to sustain and grow through multi-year grants: most social sector organizations seemed to suggest that the health of civil society organizations is something philanthropies have a responsibility to foster and build. In action, this could take the form of giving more core, multi-year grants, bringing more donors into a thematic area, funding more diverse and grassroots organizations and leaders. These actions are quantifiable, moreover, and can be engineered relatively quickly.

- Convene gatherings to build sense-making at the level of the field: Our partners shared that philanthropic organizations have a vantage that allows them to see intersections between portfolios and domains, and that can help engender thematic or geographic coherence when it comes to tackling systemic problems. Coming together drives engagement with the partner ecosystem as well as between partners, which over time can result in more collaboration and convergence. We plotted this as a fast-emerging, intangible indicator for ourselves.

- Evaluations for learning: Formal “evaluations for learning” which results in richer perspectives and shared understandings was seen as the longer arc of a philanthropies’ work. Through evaluations for learning, partners, funders, and evaluators stand to see the system as a whole and more clearly. The value of being able to see the system together is hard to quantify (intangible) and also takes time (slow emerging) but is worth investing time and effort in.

- Drive richer conversations on impact: The difficulty of sussing out the impact of programs has been written and talked about in many forums. In particular, the (negative) role of donor organizations in pushing a highly metric-focused approach has caused consternation among many NGOs, especially when one metric is valued more than another. As Mona Mourshed puts it, “nonprofits too often receive (well-intended) guidance from stakeholders like funders and board members to disproportionately zero in on a single goal: serving the maximum number of beneficiaries.” Given the power dynamics in play, our partners highlighted that RNP and other philanthropies could explore ways in which the discourse on impact could be enriched and expanded, thereby informing the future philanthropy better. This will undoubtedly be a collective journey (slow emerging).

As we search for better ways of measuring progress, Fields of View—a Bangalore-based organization that makes systems thinking actionable through tools—shows what this can look like by distinguishing between “events” and “processes.” Events are similar to what we termed “concrete actions”: x children enrolled, y acres replanted, z ration kits distributed, and so on. Monitoring and evaluation has matured to the extent that it captures these indicators well. But it fails to account for the processes that bring people into these problems in the first place; if one can see the system better, so as to intervene at the level of process, we stand to change the trajectories of people and problems currently stuck in a loop.

By deploying a systems-conscious, multi-method approach when it comes to capturing and interpreting field dynamics, we stand to increase the resolution of the picture that emerges. This is not to say that doing it is simple, of course. Running evaluations for learning is indeed time-consuming and requires engagement and co-creation. But with emergent technologies, we can start to open up new ways of sensing. Having better sensing tools for impact also allows funders to fund more as this approach reveals many more spaces that require support and funding. Fields of View put it well: “[As] most donors would say, thirty years later we don’t want to be funding the same thing.”