E4 - Part 2

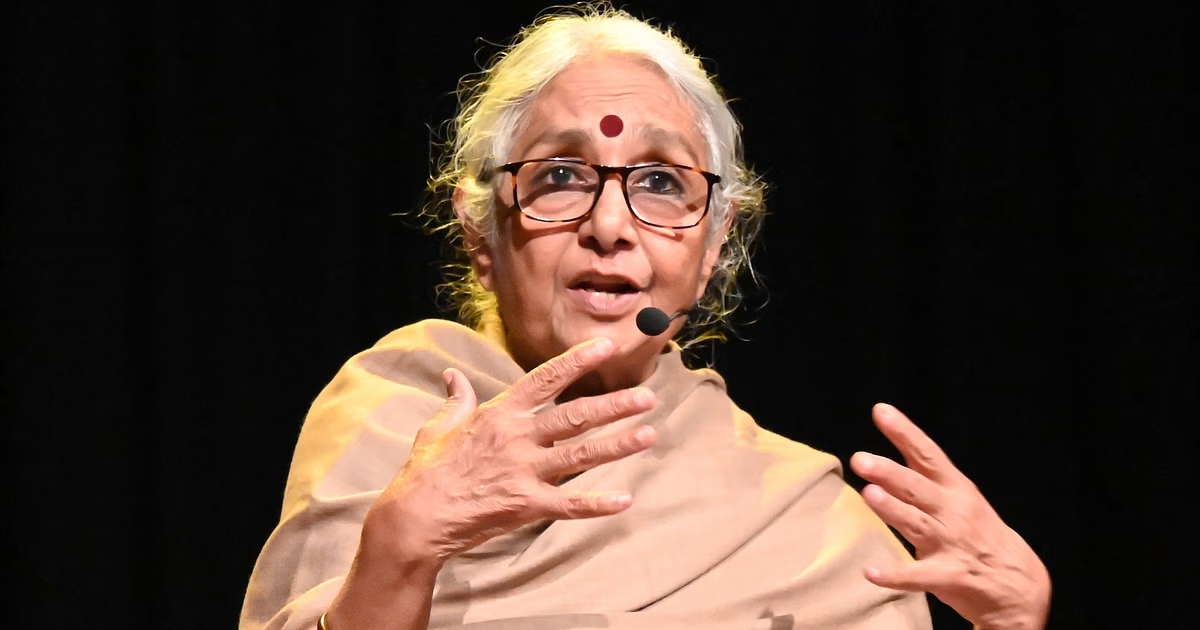

Aruna Roy: If I’m really fighting for accountability, the first person I should make accountable is myself (Part 2)

This is part 2 of Aruna Roy’s story. Listen to part 1 on our feed.

In part 1, Aruna spoke about her early life and upbringing, her career with the Indian Administrative Service and her move to Tilonia, Rajasthan to work at the Social Work Research Centre where she developed deep friendships with the women of the village, and equally learnt from them.

In this episode, Aruna speaks about her move to Devdungri in 1987, to live by the values of sangharsh, or struggle, in the search for a way to work for the betterment of society through collective action and citizen participation. She recounts how the first few years were spent learning how to live with the hardships of rural life and grappling with earning the trust of the people of Devdungri.

Along with her colleagues Shankar Singh and Nikhil Dey, Aruna founded the Mazdoor Kisan Seva Sanghatana (MKSS) in 1990, where they relied on the mobilisation of collective action in order to secure the rights of the rural poor. She also speaks of the Right to Information movement through the National Campaign for the People’s Right to Information or NCPRI, which resulted in the Right To Information Act in 2005.

Aruna Roy is in conversation with journalist and curator of Ahimsa Conversations, Rajni Bakshi.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Aruna Roy

Aruna Roy is a renowned Indian social activist, professor, union organizer, and former civil servant. She served as the president of the National Federation of Indian Women and founded the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan.

Rajni Bakshi

Rajni Bakshi is a journalist and author, who has founded Ahimsa Conversations, an online platform for exploring the possibilities of nonviolence.

We need digitalization for a number of things, but we also must understand its limitations and we must understand that it has become an accessory to power, not the dissemination of power, but the centralization of power. Then it's something else.

Aruna Roy

Reading resources:

Dunu Roy is a well known development sector leader and runs the Delhi-based Hazards centre.

Read about the School for Democracy here.

Archival Audio:

Sushila chants ‘Humara Paisa Humara Hisaab’ by Nikhil Dey

Main Nahin Maanga- MKSS Song on RTI Demand by Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, Rajasthan, India

People’s Audit to Fight Corruption by Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, Rajasthan, India

TRANSCRIPT:

HOST

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

This is the second part of Aruna Roy’s story. If you haven’t listened to the first part, we recommend you do so. In the first episode, we heard Aruna speak about her early life and her upbringing, and then her career with the Indian Administrative Service, and how she left the IAS age 28 to move to Tilonia Village in Rajasthan to work at the Social Work Research Centre. She developed deep friendships with the women of Tilonia, and equally learnt from them.

In this episode, Aruna speaks about her move to Devdungri in 1987, to live by the values of sangharsh, or struggle, in the search for a way to work for the betterment of society through collective action and citizen participation.

The first few years were spent learning how to live with the hardships of rural life. It was here that Aruna grappled with earning the trust of the people of Devdungri.

Along with her colleagues Shankar Singh and Nikhil Dey, Aruna founded the Mazdoor Kisan Seva Sanghatana (MKSS) in 1990, where they relied on the mobilization of collective action in order to secure the rights of the rural poor.

And now, back to Aruna Roy and Rajni Bakshi.

RAJINI

So Aruna now I’m going to go back to the decision to step out of SWRC and move to Devdungri, which is when we first met, you had just moved to Devdungri and the house was also still being. It was built, but it was still being kind of finishing touches on the famous mud hut of Devdungri. So can you just walk us through that decision? I mean, because you were doing very creative work at SWRC and yet some restlessness crept in, which took you to Devdungri. What was that?

ARUNA

No, no, no. There was no restlessness. Just clear hard thinking. Already wanted to take back, take a break. No, you’re okay.

Let me go back to Gandhi.

He spoke about Seva Sangarshan Nirman.

Let’s put it like this, that after my association and relationship with wages, women struggles, looking at issues, I felt, and I still believe the real change comes from Sangharsh. Others, you make far more compromises. So Sangharsh is struggle. So if SWRC, Tilonia Barefoot College was Nirman, which was development, then I was Sangarsh.

It didn’t make any sense to stay there and fight every day about every process, whether it should be this or that, this or that, this or that. It just tiring. So I made up my mind three years before I left SWRC that I was leaving and I owe much of this final clarity to Dunu Roy who told me that, forget it, I thought we could coexist.

We’ll never coexist. I said, nahi nahi we can coexist. He said, kuch nahi hoga you cannot coexist. And when I thought about it, I realized it the same sets of people, you pull them in two different directions. They may in fact be involved in both sets of activities, but at the time of their choice, not when you’re pulling them and two forces are pulling them apart, you ruin everything.

So I just decided to quit. So simplest definition is that, and so clean break and start afresh thing is Rajni. I just don’t know how I had the courage. I was 41 when I went to MKSS in the. When I went into that mud hut in 87, I was 41. But I was also driven by two more things. One was this business of struggle.

The other, which still there, very much part of my psyche is an aesthetic life, a minimalist life, a non consumerist life. Living as simply as my neighbor. Existing on the simplest food. That has a special attraction and will always have a special attraction for me. And Devdungri gave me immense room for that. And I lived without any conflict born of privilege.

There was no conflict in Devdungri. What peace. I didn’t have to worry. Does my neighbor have two saris? Whether I have one, sari, my neighbor have sal. Do I have, I’m eating so much, does my neighbor, none of that. My neighbor and I lived similarly, so there was an extraordinary comfort of, of being equal, at least in an economic sense because otherwise I was an unequal person because I was born with privilege in my head, which I could never get rid of.

RAJINI

And and what was the rule? One rupee a pav bhar? You had a rule, No?

ARUNA

That time the minimum wage was 14 rupees a day in Rajasthan, which is what we took, as honorarium. And today it’s 275 rupees a day honararium. When I went to Rajasthan, it was three rupees a day. But look at the price rise. When I went to Rajasthan, three rupees a day was the wage.

Three rupees was a kilo of ghee, and 600 rupees was the price of silver. Hmm. Now, ghee is 800 rupees a kilo, but we are given only 275 rupees a day as wages. Now you see the difference how much more, actually we should get in minimum wage to be on par with what we got in 1976. When I went there, 75, 76.

RAJINI

And if I’m not mistaken, this was the first time in your life that you lived without water, running water. It had to be fetched from the well without electricity.

ARUNA

Tilonia electricity came in the 90s to my house. I did not have electricity. There was kerosene lamps, I, there was water, which was fetched, but it was fetched in a bullock cart and I didn’t have to go and fetch it on my head, which I did in Devdungri. Devdungri I learned how to carry water on my head without spilling the water from the pitcher.

RAJINI

Yeah. You taught me also. Yeah. You used to have the smallest matka so that I could play this game of pretending to help with the water.

ARUNA

Well, it was the learner, matka.

RAJINI

Out of this living in the village of Devdungri, how did the MKSS emerge? It’d be great if you can talk about some of the people who stepped in and shaped that next phase, but also what were the essential values which created the bonds that emerged?

ARUNA

In some ways, since I traveled from one village to another village in Rajasthan, there was a continuum. I didn’t travel far into, Tamil Nadu, to Kerala, where there would’ve been a great change. I also went with a fair degree of comfort about the culture of the people, about having friends in Rajasthan, but it was also an alien place.

Every 60 kilometers, the language changes. The dialect changes. So there were many things I simply did not understand. Then I had to ask Shankar, what does it mean? What does that mean?

I enjoyed life, so I didn’t mind having to go. We didn’t have a toilet. So for two years we went behind the bush. That was, for me, the most difficult to accept, I think by, but I was trained before I came to Devdungri by living with so many people in and around Tilonia. Nevertheless, I found that difficult, and I think this was the most difficult thing for me to accept.

But as a sort of a permanent scene temporarily, everything was okay. So living conditions were all right. There was the other issue of, the rains and the snakes, the scorpions and more, more the snakes than the scorpions. Uh, but also all the little worms that would come into the house. So you had to, and we slept on the floor, so you had to put cotton wool in your ears because some of them called, there are these centipedes, which they call canchilla, whichever habit of getting into your ears.

So these are the little things which, uh, you had to take precaution about otherwise, you know, the food or the other things. So not issues. And of course, we walked everywhere, which was great. And then we began our conversations with the most advantagous thing about going to Devdungri was that we were surrounded by Shankar’s relations.

RAJINI

Yeah. Shankar Singh, who had earlier worked in Tilonia, in the communications unit. Am I right?

ARUNA

Shankar [actually came to TIlonia, in 1980. When I had already decided that I was going to quit, but he, we stayed together for three years and we became very good friends. Shankar is a phenomena, he’s one of the most extraordinary public communicators I’ve ever seen.

Addition to any theater group, he would’ve been, Karath actually said he should have been in proper theater and that we were wrong in taking him away to where we did. But anyway, Shankar was a super communicator with a terrific sense of humor. So he made friends everywhere and he and I became friends through arguments and differences.

He used to come and say to me, Bunker is a very nice guy, and you’re so aggressive. So I used to say, really? Then I said, what do you mean, what am I aggressive about? And so we had our first differences in disagreements about women. And he was of course a totally traditional man. So he had to, he changed over so many arguments, so many differences and so on.

So that was the first thing. We didn’t have a sort of everything tickety boo relationship. We also had our differences. Anyway, I got interested and I always had a great interest in theater, so I got interested in the communication section. When they first made the puppets, then they went for their training.

Then I met Tripurari Sharma. There’s a whole new world opened up because of Shankar joining the SWRC. So we were, we were friends and friends. And so when we both went to, to together to Jhabua, to work with the tribals for a while, because one of our fellow colleagues from Tilonia had gone there, Kemraj and Nikhil at the age of 20 then joined us.

I still feel I, my dream was to work there in the tribal area, but they wouldn’t have me because I was a woman, because I was powerful. They didn’t want me. So with lot of dejection and sadness, I came back from Jhabua. Shankar also wanted to work in Jhabua, but they said they wouldn’t pay him any money. And he had a family, three children, so he couldn’t continue there.

The only person they would keep was Nikhil because he had come from an affluent family and he didn’t need any money. But, uh, by the time Nikhil and Shankar had become very good friends, and I had become very good friends with Nikhil as well. So we decided we would work together. One of the interesting things about at least my moving to Devdungri was that I was determined that I would only work with people with whom I had a great degree of comfort. Mental comfort.

RAJINI

Yeah. A kind of at a visceral level.

ARUNA

Yes! So that you could agree, disagree, argue, fight, quarrel without losing the relationship because this work brings out all these issues. So you can’t become enemies just because you disagree. In any case, I was brought, brought up to believe in dissent in my own family, biological family.

But I also lived constantly with dissent with Bunker. We never agreed since university days, we were known to not agree that there were many people were surprised when we got married because how we persistently disagree on most things in life. How did you get married? So you can agree on fundamentals and disagree on everything else. That’s also possible. You can agree, disagree on fundamentals and agree on everything else. And then life is very much more difficult.

So in any case, so I, we needed this group together, so that’s how we came to the Devdungri and Shankar’s relations around. And Anshi, his wife refused to go anywhere, but she was not comfortable.

And I wanted to work in Rajasthan’s tribal belt, but, uh, she would not move even that 150 kilometers. So we settled down in Devdungri because we settled in Shanker’s sister’s cousin’s house. It was in a designed, in a manner which was not comfortable to us.

Say there were no windows in the cottage, in the hut. There were so many chulahs, so we had to remove all those stoves or earthen stoves. We had to make them into rooms. Then we, the two goat sheds were made into the kitchen. One goat shed was made into a bathroom. So all that construction had to take place.

And the division of labor was that I cooked and they all worked because I could not lift stones and all of that. They, they did all that. So we actually constructed a bit of this re refurnished, refurbished mud hut ourselves.

Giny Srivastav, very well known woman activist in Rajasthan social worker. She told me, you are indulging yourself. She said, you should go where you can reach far larger number of people. What do you mean by withdrawing into a village hut and living this romantic life. And we also had a goat, by the way, by the time yes.

So Ginny was absolutely shocked. She said, you should have been going to a much larger frame. Why you shrinking it? This little one, kya hoga yahaan se? You live a romantic life will fetch your own water. You cook your own food, you’ll have goat. Then what?

I said then if we fail, we come home bistar baandhke we will go. But uh, I must try it out once. But uh, by the time Nikhil was still doing law, he used to keep going off to Delhi to give his exams and uh, Shankar and I had what neck deep been working two months. We were organizing people to work for ask for work and for wages and of course, this usual thing. They were wondering why we had come there.

So were we, uh, people that come to mine were, we keep people coming to look for labor. We were contractors. What were we they could not make out. And, uh, the people who lauded over us, was the neighbor who was a suppo, you know, a jawaan. He thought he was superior to us because he had more furniture in his house than we had.

It was really interesting to see how superiority gets established and there was so much animosity. And because we opened up our kitchen to dalits

every day there was a fight. And because Shankar and Nikhil went to fetch water on their heads, Anshi used to get it from them, you’re a useless woman. You make your husband get water on the head, why don’t you get water on the head?

Kammu went to the village well, the daughter, she was about 12 and she fetched water, but she couldn’t, lift the pot to her head. So the gentleman who owned the, well was Agodaji, was a dalit so the whole village used to take the water from the dalit well.

Well, but he couldn’t touch their pots. Amazing. So, because she made him lift the pot, they came in, hoards, break the pot, don’t drink the water. We had a huge row with them. Finally, I said to them, if you persist, I’m going to the neighboring town Bhim and I’m gonna register a case against you for untouchability.

[MUSIC]

ARUNA

Under the atrocities Act you get bail in Jodhpur because you can’t get bail local. Then they went. Then slowly the fact that this would be an open kitchen, then they all attacked Shanar’s cousin for giving this house to Shankar. So we lived where actually, I tell people that you talk about inequality, untouchability in a theoretical sense. Even if you live in a campus

It’s half theory, but when you live in a village, it’s there every minute of the day. Yeah. Somewhere or the other. It surfaces. And I think it was extremely important for our political work that we lived there.

RAJINI

Aruna, I think one of the other things that had a big effect was that, even when known to be powerful, people came to that house Anil Bodia, or maybe the local SD uh, collector or somebody, they washed their own vessels, that nobody was exempted from that domestic practice of everybody washing their own dishes. Did this have a positive and creative effect, or did this also raise resentments?

ARUNA

This raised more resentment with the visitors than with the local people. Local people might have wondered, but many of them are cooks. They’re all people who work in these dhabas migration from the Devdungri area, large numbers go and work.

Chunni Singh who went from us used to wash dishes for so many years. So washing dishes was not considered a woman’s job. It was considered the one was least powered in the washing. That’s all. It was not considered a woman’s job, but for those who came, it was effrontery. It was, uh, lack of courtesy that you make your guest wash the vessels and all that.

So we always used to say, you say, always said that you’re not washing the cook vessels in which we cook. You’re only washing your own plate and your glass, the tumbler in which you drink your katori. That’s all. Oh, your You’re not going beyond that, but that you have to do. Professor Hanumanth Rao washed it when he came as, uh, member planning commission. So it was not just Local officials.

[MUSIC ENDS]

HOST

In 1990, Roy, along with Nikhil Dey and Shankar Singh founded the MKSS, working for the minimum wage struggle, to improve social forestry programs, and fighting for the transparency and accountability of government schemes. Roy was central to the Right to Information movement through the National Campaign for the People’s Right to Information or NCPRI, that resulted in the Right To Information Act in 2005. She has also been an instrumental part of the campaigns for the right to work (NREGA) and the Right to Food.

RAJINI

Yeah. So from all of this bubbling dynamism, how did that 1st May 1990 come about when MKSS was formally launch? Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sanghatan.

ARUNA

There were two important struggles, which made people realize that if they get together and form an organization, their bargaining power increases exponentially. The first struggle was about minimum wages on a work site in which Chunni bhai and Bhanwar then filed a case which went on, and finally we won it many years later.

But the second and more powerful one was the demand for forest land, uh, allotting social forest. Social Forest used to be a program where the allotted, uh, government pasture land for developing into a social forest and Lalsingh and Tejsinghji two extraordinary men. And with the Bhuria and Kaki, the to women in that village, we managed to mobilize the entire village to oppose one of the most copy book bad characters I have ever come across was, was Hari Singh.

Hari Singh of Taal. Hari Singh was the son of a local thakur, which is a local landlord. And that thakur had burnt the national flag when we became independent. For what reason he did that, we don’t know. But Hari Singh, who was the son of that man, was a terror. He was a complete, he was like the chap in Sholay I mean, literally like the chap in Sholay. So he terrorized women, he terrorized the people, he terrorized everyone in Sohangarh.

So got the Sohangarh, people were fed up, like if they grazed their cows in the pasture government pasture land, they had to give him half the milk, half the ghee if they took you know, clay from the, from the pond. Yeah. Then they had to deliver half the clay in his house. It was ridiculous. I mean, it was complete and total oppression.

So Lalsingh decided that he needed to be opposed, and Lalsingh and Tejsingh was far senior to Tejsinghji. So we decided that we have to take this up.

So MKSS designed the social forestry program so that we would, Sohangarh would ask for 25 hectares of land to grow social forestry. I don’t think my words can capture the, the, the depth and the horror and the violence, potential violence of that entire event.

And I don’t think they, even the people who join us today can just imagine it, but they can’t feel the, the, the extent of it. So for two years we battled and he threatened to have me raped. He threatened to have, he did actually have Shankar and Nikhil beaten up. Many things happened in the course of that. He came with guns when we were allotted the land.

And the government, of course, allotted the land because we were well known to government. They alloted the land. We created a women’s organization strategically because Rajput, women never go out to work. So we said thakur’s Hari Singh’s wives and children will never come there. So we created a women’s organization and uh, then we also built this extraordinary, uh, boundary wall.

And then we grew a great, very good forest now, but the whole thing made people realize that we have to get together. So it was not an idea that was born from the heads of three people who went and settled there, but from the actual people, people who actually struggled, who realized that unless we get together and form a unit, our bargaining power is zero.

Yeah. That’s why the MKSS debated on for over a year. And the name was given by local people. We wanted to call it Mazdoor Kishan Morcha or something. They said nahi nahi morcha porcha humare shabd nahi hai, we have to call it Sanghatan. And Shakti. Shakti must come in because we are fighting for power. So Shakti must come in, so that’s why Mazdoor Kisaan Shakti Sanghatan. That’s what preceded the 1st May, 1990 when we actually declared the organization, we chose Bhim, which was the local casbah town.

Yeah. And in the open space that they have for public meetings. We went there and declared it. There, began our history

RAJINI

And at, I think the first struggle was for, uh, full minimum wage to be paid in the famine relief works.

ARUNA

The Jawahar Rozgaar Yojana. That used to be a program run by the government where they used to give some amount of work for, for people without employment.

RAJINI

Okay. Not just the famine relief works.

ARUNA

There was also famine relief works. There was also JR work. Yeah. Both used together.

RAJINI

And so from minimum wages to the right to information, what was the process? How, because I know that there was a connection because it was in the process of doing the minimum wage work that some of these issues came to the fore

ARUNA

Let’s put it like this, that the minimum wage history for me goes back to Northeast Great battle for minimum wages and my initial years to, so minimum wage battle was an older battle. Mm-hmm. information was also somewhat semi formed earlier idea. And but the sharpness of this information demand came because of repeated asking for things from the local government and not receiving it under the protects that they’re covered by the official secrets Act [01:31:00] BPL list

we could not get, we asked for simple information would not be given and we knew it, that they don’t give it. But this [ sharpened the debate and because on every work site when we asked for payment of wages, they would say, you did not work. And we would say, produce the register. And they would say, we can’t show you the register because it’s a secret document.

We can’t produce the bill and voucher because it’s a secret document. And we sat on two fastened to death. Yeah. Than us, I remember. And they were massive. The first one, the collector came and told us he’d give us our minimum wage. We got up. The second one shook the state government. Cause we were just five of us, representing five districts who sat. It was panchayat elections.

Every village they went to, people said, you give us information or go home. Because the chief minister, because of fear, had made a statement that he would give us the right to information and he didn’t. Later on, but at this time it was already an issue. It had become an issue. So then it had become hugely public, this issue.

And when we sat on the second dhanna, government stopped a hundred crores of an installment that was due for JRY because they paid 95 Pisa a day in one work site. Either you don’t work or you get wages. What is 95 paise a day? So unearthing all this information had phenomenal impact on them. Yeah. And we also realized that information at many levels was necessary.

And even in the fight for Sohangarh, for the land, Hari Sing would have that particular number of that particular land not put up for allotment. So if information can be used negatively, information is be used positively. So there was no question. So it was a growing awareness.

When we sat in that mud earthen aangan our house when we were talking about we can’t do another fast to death, we won that battle, by the way. Yeah. We won that.

RAJINI

No, but it was very scary.

ARUNA

It was, yeah. They came and pick, pick us up when people are fasting and they did all sorts of things with us and yeah, they didn’t beat us up just short of beating us up.

They did everything so, when we discussed post that and how many times will we start sit on fast unto death? Then Mohanji and all of us were there, but I think it was Mohanji who said, if that information doesn’t come out, we’ll always be liars to prove the truth of our statements. we have to gather that information out.

And I like the way he said it. He didn’t say that we want our demands. You know, met, he said the truth of the statement must be met. And then of course it grew into a huge demand.

RAJINI

But this very evocative, uh, slogan, Hamara paisa, Hamara, hisaab. Where did that come from? Because it, it puts the whole thing in a nutshell.

ARUNA

Well, this thing evolved. We had these jan Sunwaiis in which we asked for information, and in that information, government denied us the information. We had four demands, all panchayat records must be out in the open. That, that there must be accountability fixed for people who do not exercise their obligation. Then there must be public accounting, which we call social audit.

And then we called, then we said we want redressal of all the amounts. Now, when this thing grew and government still didn’t respond, and we said we, the, the chief minister made a statement in the assembly saying that transparency of records would be, panchayat records would be transparent. So then we asked for that to be implemented.

So the Beawar dharna in 1996, when we sat in Beawar, we are, by the way, crowdfunded, we don’t take any funding from anywhere. So crowdfunded. So we went to 300 villages saying that, will you give some of your time and four kilos from each family to support us to the dharna cause we have to eat out there.

So when that came and we did the dharna at that time, we got all of India involved. Cause Prabhas Joshi came, Nikhil Chakravarti came, Kuldeep Nair came, Ajit Bhattacharya came. Then we had Mae Dhakam, Swami Agnivesh come. So many people came. So it became a national event, Beawar 1996. After that, we’d framed the law. The then Prabhas Joshi argued that, and Harsh. Harsh was also there, Harsh Mandar. And they both argued that a legal instrument was very necessary to overrule the official Secrets Act.

And for that they went and they went and parled with the Press Council of India. Justice Sawant was then chair. Justice Sawant agreed that they would oversee the first draft of the RTI. Meanwhile, because of Harsh we had already gone to the academy and the first draft had kind of roughly been prepared.

One clause has come to us till today when we were wondering what would be the positive list and the negative list. NC Saxena was then director. Just came and said, when we had argued ourselves sick, we couldn’t form the right the, the what we could and what we couldn’t see. He came and said, why? What? Your representative can see, you can see. You’re a sovereign.

So whatever member of parliament and the member of the legislative assembly can see, you can see. It’s as simple as that, which is a formulation there in the law. Even today, when we took the first draft for presentation to the world, you know, to the nation in a manner of speaking, there was a huge press conference, IK Gujral, VP Singh, Justice Sawant, the whole lot of others, lawyers, editors, et cetera, were there.

And from MKSS, 4 or 5 of us, or six of us went. One of them was Sushila, and she was asked by a journalist, how much have you studied? She said, up to the fourth class. So he said, what are you doing here? How can you do anything for it? Look at these people, they can’t get the loan. You can get it. So she stood up straight and she said, when I send my son with 10 rupees to the bazaar and he comes back, I take his accounts.

The government spends billions of rupees in my name. Won’t I ask for accounts, our money, our accounts humara paise humara hisaab. In hindi she said yeh humara paisa kharch karte hai, inse hisaab nahi lenge kya? Yeh humara paisa hai, humara hisaab.

RAJINI

Beautiful. At the same time. There was a challenge of how to keep this growing network and organization together in ways that are internally democratic also. And we all know that the moment you go from say 5-10 people to 50 people and to 200 people, those issues of maintaining an internal democracy, and especially in your context where there was so much emphasis on being non-hierarchical, how did you, what were some of the creative and both difficult elements of this dynamic?

ARUNA

Structurally the audit process, the social audit process brought in by the, MKSS has become now a part of structural governance. Yeah. Which is, ineffective, which is partly successful. Partly a failure some were very successful depending on the government, depending on all that. But we also said there are three forms of things.

What is the social audit, which is a mandated form of audit it done by the government, but we said There’s also something called a jan sunwai when people demand that there should be an audit of things that are going wrong in their area. It’s democratically obligated for a state to conduct an inquiry publicly.

But we also said finally, there should be a transparency meeting where we ourselves disclose what we are doing to people, which we did as a shops have a disclosure meeting. We all have disclosure meetings in which we lay our accounts on the table for people to see so that they know what we are doing.

And that also has been an important thing in some NGOs, like SWRC Tilonia has done it has had disclosure meetings, but not too many. One, one during the time when they were accused of, uh, and the police and the authorities went after them because they decided to settle my scores by attacking Bunker.

In 97, so 1997. So that kind of thing has happened.

RAJINI

No, but that’s what is very important to convey, to future generations. And even what is, how does that happen? Because there are disagreements in any group. So how do you resolve them without any one set of people throwing their weight around?

ARUNA

There are disagreements possible on policy and on opinions. In terms of finances. There is no disagreement possible. It is completely a non-negotiable area, but that should be transparent.

Now whether you agree on whether that money should be spent there or not, there is your private business, but that it has been spent is public information and that it must be out there in the open. To jump many years after Jan Soochna portal, which the government of Rajashthan has now put out

They’ve given it the second government to do it has been the Karnataka government where 150 departments of the government have under the right to information law section four of the right to information law made the information public in real time. I don’t know how many crore people have accessed the Jan Soochna portal and how many crores have downloaded information from the Jan Soochna portal.

Yeah. And in real time, you know whether your ration shop has given someone ration in your name or not. It’s vital for the poor. Yeah. So that culture has come in. The NGOs have not been so forthcoming, but they also have to now manly, put forward at least their audited statements on websites. Yeah. So that everyone can see it.

So I think the culture has changed. And basically, what is it, Rajni? It’s basically the right to ask a question.

And that has impacted, brought violence killed hundreds of us or more hundred information seekers have been killed. But it still continues as strong as ever. Yeah. Amra Ram just recently in a place called Barmer in Rajasthan, his legs were broken just because he asked questions about NREGA spending just about six months ago.

But it has not stopped him. He comes on a stretcher to our meetings to say information must be given. It’s the determination somewhere to get that out because it doesn’t serve my purpose alone. Yeah. It serves the purpose of many other people and of something called development, something called progress, something called benefits, something called welfare.

Yeah, something called humanity. Yeah. That’s somewhere struck a chord. And that’s why I think, and the right to information has been though it began with a poor people’s issue. It has gone across the board to so many different kinds of institutions and sectors. Yeah. So I think strangely enough, I have met people who don’t know me, uh, who are from, uh, the corporate world.

Oh, come to me and say that, you know, you may not agree with us, but you know, the right information has supported us as well. So I said I may, why should I disagree with you? Always areas of agreement and disagreement. Mm-hmm. that we agree on something is the beginning of a conversation. So let’s start conversing

HOST

Throughout her life, Aruna’s focus has been on working collectively. It’s what she believes is necessary to create the kind of change she’s interested in. In 2000 Aruna was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay award for community leadership.

RAJINI

Yeah. Aruna I want to step aside for a minute and uh, address an issue that I know you have struggled with a lot, which is this very delicate balance of being the first among equals. Cuz I remember when you were, uh, going to be given the Magsaysay Award, how much you agonized about whether it was at all correct for you to accept the award when the work was done as a group, I know you had similar agony in accepting when Sonia Gandhi invited you to be a member of the NAC and we’ve had this discussion many times.

But for the purposes of this exercise, can you share how you have resolved that dilemma? Because you are in able to be in certain positions and play certain roles that everybody can’t. And, uh, so how have processed to that.

ARUNA

It’s resolved and unresolved. It’s a statement that MKSS and I, and all of us, But despite that, the Magsaysay people accepted that they would do it from the next award onwards.

They wouldn’t accept it in my case because they said it was pre decided. But I would say to their credit that Carmen Cita Abelia, who was their general secretary, came and spent two nights in Devdungri after the award. And she also wanted to go to Chunni Singh’s village, but she couldn’t. And Chunni Singh who accompanied me to Manila, was totally accepted by them. Usually husbands go, this husband was not going. Or You have some angrezi bolne waalas going. But Chunni Singh was totally-

RAJINI

I think you should describe him-

ARUNA

Chunni Singh is one of the most remarkable people I’ve met who has an innate sensory equality. He just doesn’t believe he’s not equal to anyone else. Just studied up to class two informally, has washed dishes. From the age of four in dhabas, has been a kind of Robinhood in his fighting for workers’ rights in Baroda, gone back to farm on his own land, and if Chunni Singh’s with you, you have hundred people with you in terms of courage and integrity.

He’s a remarkable person, very outspoken, often very rude. So it was a decision as to who would go with me. So Nikhil and Shankar said they were not going, so who else would go? So in this discussion, that took for a day or two for us to decide on who would go.

Finally, they said either Lal Singh or Chunni Singh should go. Lal Singh hates Traveling. So he said, I’m not going. So it was Chunni Singh. When Chunni Singh went to get his passport, some documents from the SDOs office, that fellow the tehsildar that called 10 people. And they all laughed at Chunni Singh are ye jayega? Dekho isko deskho! Kya award lene jayenga? Tu jayega? Like that. So anyway, Chunni Singh said tumhe kya jata hai, main jaunga.

You know, he answered them, but he had to be clothed, he had to be furbished and everything. And finally he went with me. Chunni Singh would never accept that he did not know anything. This, I think if you all of us know, so when we first landed, there was this banquet, and even I was a little worried because there was so many knives and forks, and I thought, God, which one goes first, you know?

So he said to me, Hindi, he said, yeh kya ho raha hai? I said, pata nahi whatever I do, you do. He said main meat nahi khaunga. I said, theek hai I also won’t eat meat, so you won’t eat what I don’t eat. So he ate with so much elegance. I was shocked. He was absolutely elegant. He did not, uh, mismanage his cutlery. He did not behave with any kind of lack of decorum, and he managed by the time he left up a fried egg on toast without spilling any of the egg on himself, I thought he was marvellous.

So just to show what kind of presuppositions we all have, but Chunni Singh went there and they all liked him very much. The arrangement was that wherever we had to talk, I talked questions and answers. Chunni Singh answered 80% of the answers were Chunni Singh translated into Hindi for him, and he stunned them because he was so brilliant.

So actually one of them said, we thought you were the Air India maharaja when you turned up because,

Because of his safa and his dhoti usual Rajasthani dress, which went. So Chunni Singh is a remarkable man. Yeah. He still continues to be a remarkable man. He doesn’t want to take even an honorarium. He doesn’t take money from anybody. He wants to retain his independence to such a degree that he would rather just eat the minimum that he can and live the way he does rather than be anyone’s servant.

Yeah, he’s an amazing human being.

RAJINI

And the NAC experience?

ARUNA

We have received, by the way, many awards in which I have been singled out. Yeah. Whereas I’ve made all these statements, but we have not been able to really fight the system unfortunately, and I’m very happy to say that in the MKSS, I’m only one, of many.

Yeah. That of course is the balance that I really need. The NECI went to every institution and every campaign I was a member of, no, including NAPM. NAPM had a huge debate. There was a division half said I should half said I shouldn’t, or rather maybe 60 40, but it was Medha’s vote that made me go.

She said, no, Aruna must go because if she goes in, she’ll at least take our voice in. She must go. And if Aruna goes, she’s accountable to us so we can make her say, carry our views. National Advisory Council was actually set up by the UPA one because they made a set of promises to the people of India, which was itself remarkable.

Which was because it was a left and Congress and many other progressive parties Alliance. It was called the National Common Minimum Program, which they made huge promises to the people so that they would be, in a sense, be accountable. The National Advisory Council was set up to monitor the National Government Minimum Program, which was again, a remarkably progressive democratic step.

But nevertheless, to be a member of the NAC with Sonia Gandhi as the chair was a difficult proposition. Yeah. And I remember again, the whole process of approvals had to be got. And I remember going in meeting Mrs. Gandhi before I became a member, to say two things to her that I would speak my mind out, that I would disagree with her or with the Congress government or with the UPA.

Would she allow that? And she said, yes. It’s on that basis that I joined the NAC. Yeah. And I always feel that is a remarkable difference.

I carried so many of their petitions, their [proposals, the Hold the Land Aquisition Act ideas and the proposal, the proposals we organized when I was in the NAC, we organized so many public consultations, which were all possible because of Jean Dreze, me, so many others being members of the NAC one, NAC two had much larger representation.

RAJINI

Yeah. But on the whole, when you look both at the phase where you were there and then even later, what would you say on the whole is your assessment of the limitations of such a exercise, of bringing in different elements of Samaj and civil society and other elements in even the private sector and trying to come up with these kinds of, basically it was a platform, I think, for dialogue between all these various dimensions for the common good. So what were both the limitations that came to the fore and what did against all odds get achieved?

ARUNA

I think, you know what they failed to do, despite the national campaign for people’s Right to Information persisting that they do, but that they fail to create it as a pre legislator platform for looking at policy and legislation and allowing participation for people’s voices to be heard.

Which is what, which is what in essence it was, but they did not make it into a statutory body which would per force have to do it for every legislation that came thereafter. Yeah. That was, its I think, failure because it failed to define itself. Yeah. But the asset was that by having senior members of government within its formation, it was able to pull in the kind of power that people’s voices never can pull in.

Access to government secretaries, access to ministers, access to Prime Minister, all that became possible. Not that we pushed them into anything, but that we could at least sit as reasonable equals Yeah. To argue out our point of view. That became possible. And Sonia Gandhi was a good chair. She allowed us to speak.

She allowed us to argue and fight without interference. She listened more than she talked. Of course, the decisions were always hers as well. In the end, she didn’t, she was not a weak person. She took her decisions, but she never disallowed us our freedom to argue and disagree with her or with each other.

They were, they reflected the public realm. Yeah. And in the case of the RTI and the MGNREGA, without political will, these laws would not have got framed. Yeah. Least. And food security also, all these, all these rights based legislations. By the time the second NAC came, there was resistance building up and already had built up from bureaucrats, from political, uh, power bases from so many people.

Yeah. But in the first, first, NAC took the bureaucracy by surprise because we had a formulated law, which they truncated, but yet in standing committee, we were able to change it…that allowed the whole process to go through, even in allowing the parliamentary procedures to go through it, the process to go through and mandate it. Right. I think the laws were greatly benefited. So I think that the creation of the NAC did help in many, including the land acquisition law to a great degree.

But then it, it got truncated, but many of these right based laws would not have been possible without this kind of platform and that platform facilitated it.

RAJINI

And what is now the scenario going forward, how does it look today? Say, if you visualize the next 20 years?

ARUNA

I can’t visualize the next 20 years. I would like to just look at myself today. Now I feel that the public discourse has been muddied.

There was a certain degree of clarity which has gone completely haywire. Cause every time you raise a real issue or a critical issue before it can get even completely articulated, it’s muddied. So what happens is that instead of discussing the real issue, you are fighting a defensive battle about a subset.

I think what our younger generation must understand is to really separate the critical issues from the sub-issues and subsets of issues which are thrown in to divert our attention, we must keep absolutely to the basic questions. And there are some very basic questions, which I can call me old-fashioned.

You can call me anything, but I cannot go away from, and that is that this India that I know of and I’ve lived through has been what it is because of the Indian Constitution. Dr. Ambedkar was very worried even after giving the constitution to us and said, only if the nation is beyond the party.

If the party or politics becomes more important than the nation, India’s finished. Radhakrishnan said, was not exactly a radical person in terms of politics. He was more on the conservative side. But even he said, if we get involved in caste and creed and all those regressive, you know, regressive kinds of concepts that exist in this country, we are ruined.

At the time of independence, we had the option of becoming a theocratic state. We took the option to be a secular state because of the nature of the country that’s called India. Yeah. If you deny secularity and if you deny, it’s basic right to be, freedom to express dissent. Dissent, disagree. If you disallow the right to freedom of expression, then this country cannot last. I think this is a firm faith and a belief that I have, especially since I in India, I do not belong to one culture. I’m a Tamilian who has lived in North India who married a Bengali. And I see even within the variations of these three broad formations, I see so many differences.

How will you contain it? Unless you have these principles which are there in the preamble to the Constitution and the chapter on fundamental rights. We deny them, and in one sense, we deny India.

RAJINI

Aruna where in this does the digital revolution fit in because in many ways, theoretically, the digital age makes information so much more accessible. But is it, do you see the digital age facilitating information democracy?

ARUNA

Digitalism or digitalization or digi the digital world or the whatever you, technology, whatever you call it, is neutral. But it’s use can make it the best or the worst thing that has ever happened to mankind. Humankind. Yeah. Today I think digitalization is seen by those who want to centralize power as one of the most potent weapons for impunity, for non accountability, for misrepresentation, and for disallowing people access.

For instance, every time you talk about digitalization, corruption comes in as the issue on which you’re going to really bring down corruption, has it?

We are as corrupt as we’ve always been in rural India, despite digitalization, the only people who have been excluded, other people who have no thumb prints, who don’t know how to access it, because there’s no internet in that area. There isn’t, but it doesn’t deal with corruption. We need digitalization, of course.

We need digitalization for a number of things, but we also must understand its limitations and we must understand that it has become an accessory to power, not the dissemination of power, but the centralization of power. Then it’s something else. So we have to see, that’s why the Jan soochna portal, which I mentioned was so important for us because when Rajasthan government said they’re going to have a digital dialogue, we said, you have the dialogue with us first.

Let us be the first ones to decide how to use that digital Yeah, digital platform. You will do it for us. We will put section four on the digital platform. You will not go doing something that we don’t want. So we bargained and we got this, this, and it’s an important thing because it’s, it’s a place which is a, it is a field in which you, you fight for power now. Whether it’s power for the people or power for the controllers of people is an issue.

RAJINI

So in closing, let us look at the School for Democracy. That’s your, it’s your investment in the future. And I find it fascinating that the School for Democracy is serving as a platform both for very privileged youth of the metropolitan areas. You know, I think you have many law colleges that send their entire class for a week or 10 days to school for democracy. And it is a place where village level youth are gathering, uh, for various kinds of camps and workshops. Two dimensions here. The first one is, what are you seeing in the youth aspirations of the youth?

What are you, what are you, many different aspects of the aspirations of the youth and the other is how is this, what is this showing you or either making you hopeful or not hopeful about the future of democracy?

ARUNA

Can you talk about youth as if it’s one consolidated, massive people with one idea? It isn’t, of course. So what I think would be right to say is that youth has become aspirational in a manner in which we were not. That the aspirations are now all towards material wellbeing, which the market has contributed heavily towards advertising jingles, this and that and the other.

There’s so many things, I won’t go into it. So aspirations are all very materialistic. So the idea of contribution would only be in terms of how much money you generate. It’s not in terms of how much value you generate. In terms of benefit to humankind that you don’t think of? No. So that’s one big change, I think, which has come to me.

The other one is that competitiveness has reduced the collective to individuals. Now it’s become, because of the competitiveness that has come in as a kind of idea and as a value, it’s individual versus the collective now, because the collective idea itself is being derailed slowly and democracy is collectivism.

Yeah. So to that extent, I think democracy is going to be weakened because we bring in the whole notion of the individual benefits, individual aspirations, individual homes, individual everything. And the entire system is now catering to that. Mm. So whether you see the market economy or you so see we all need markets.

The point is how do you run the markets? It’s not a question of not needing the market. That’s an absurd situation. Nobody can, none of us can live without a market. The idea is how should the market be run? Who gets to regulate it and who gets the benefits of it? And on what value systems.

RAJINI

But Aruna, in the School for Democracy interactions with young people, what are some of the signs of hope that you are seeing? Because when they do come to the School for democracy, in a sense you are introducing them, or if they already are familiar with it, you are reaffirming the value of collective action. So what are some of the signs of hope or, or of creativity that you are seeing in these interactions?

ARUNA

I, again, do not want to speak only about the youth. The point is that many people have been denied access to both information and knowledge.

The schooling system has failed cause it only teaches you the syllabus if it teaches you anything at all. Even that it may not teach. Families have re stopped talking narratives and stories to their children. The television has made inroads into families. So the time the family would’ve sat around talking about what happened or this or that is now taken over by the television.

So you have generations of young people starved of any kind of historical knowledge apart from what is fed into them. There is no information without the desire to indoctrinate in the public domain. Now, what they really need to know is the information and knowledge that has come down or is currently popular.

What are various, what do various things mean? Just to understand what’s happening. Yeah. So that they can make informed choices. They’re not making informed choices today. They’re making choices which are preordained by people. They need to make informed choices. And the school for Democracy is trying to help through a pedagogy of participation and interaction and debate and disagreement and consensus as to how you really reach that kind of place, where you make informed choices.

RAJINI

So in closing, Aruna what are your dreams? What is, what is keeping you what shall we say at the, at your post?

ARUNA

Ultimately, I have to live with myself and I can’t live out someone else’s truth. I have to live out my own truth and then I have to live it out in a manner in which it is of use to a body of human. Whatever structure gives me that facility. There I go and there I am, but I can’t speak someone else’s truth and that is what is keeping me on, keeping me going.

And I hope that one day there will be an understanding of where truth lies in this whole mess of information and media, and social media and all that that is and speculations that surround us today that the truth shouldfinally find its own balance and its meaning for many of us.

RAJINI

Thank you so much.

HOST

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.