E6

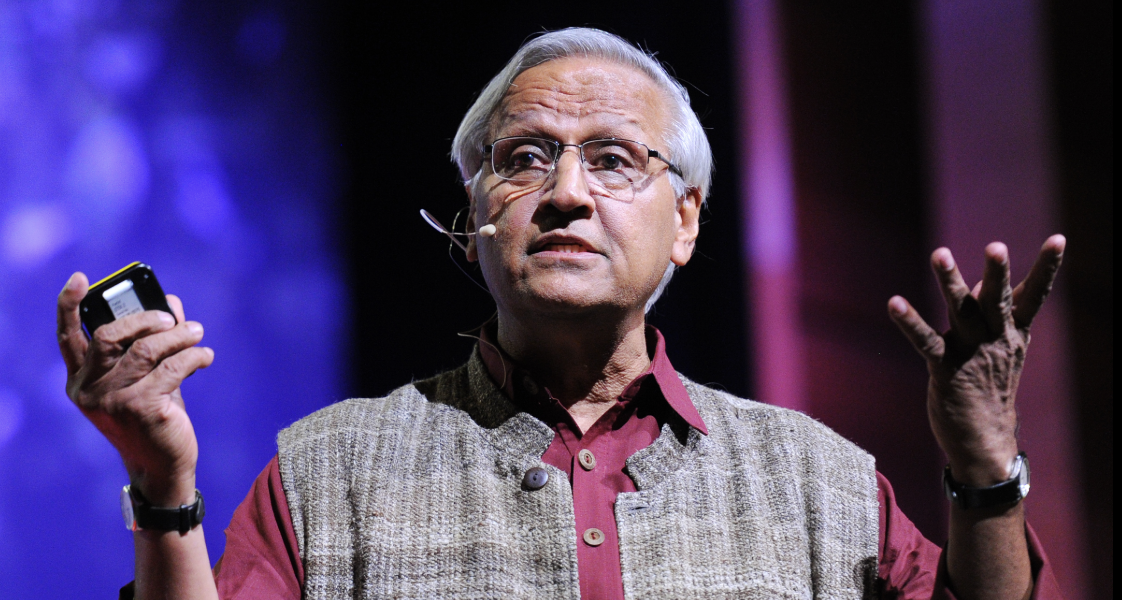

Bunker Roy: There is no urban solution to a rural problem

How did a Doon School and St. Stephens College Alumni end up spending his life in service to rural India? Bunker Roy, born Sanjit Roy in 1945 in Burnpur, Asansol, had a privileged, elite upbringing. But a visit to Bengal during the famine in 1965 affected him deeply and made him question the privilege he enjoyed. This led him to reject a prospective career in the private sector to work in rural India.

Bunker moved to Tilonia village in Rajasthan and began working on water issues in the drought-prone region. In 1972 Bunker set up the Social Work and Research Centre, and their work expanded from water and irrigation to include broader issues such as empowerment and livelihoods. The Social Work and Research Centre, now called the Barefoot College, is built on Gandhian principles of practicality, local indigenous knowledge and self-sufficiency.

The impact of Barefoot College is difficult to quantify and goes well beyond the thousands of rural women from across the world who have been trained as solar engineers to include innovation in water, energy, livelihoods, education and sustainability.

In this conversation with journalist and curator of Ahimsa Conversations, Rajni Bakshi, Bunker talks about the challenges during the early years of Tilonia, the difference between education and literacy and why we should all think about living in rural India for a year.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Bunker Roy

Bunker Roy is an Indian social activist, educator & founder of Barefoot College – an organization that aims to empower rural communities by providing essential services and solutions that foster self-sufficiency.

Rajni Bakshi

Rajni Bakshi is a journalist and author, who has founded Ahimsa Conversations, an online platform for exploring the possibilities of nonviolence.

First lesson, never depend on professionals from outside, urban professionals from outside. Always develop the capacity and competence of people from within the organization first because they are the ones who will be there to stay forever and ever. So that was the first lesson I received and it's helped me up to now. Because I think we must develop the grassroot leadership. And and depend on them to carry the organizations. The second thing I learnt was that there was a difference between literacy and education.

Bunker Roy

Additional Reading:

Coverage of Bob M’Namara’s visit to India in the New York Times Digital Archive

NGOs and Civil Society in India by B. S. Baviskar

Caring Economics Edited by Tania Singer and Matthieu Ricard

Archival Audio:

Solar Mamas of The World | Barefoot College by Barefoot College International

TRANSCRIPT:

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

Sanjit Roy, better known as Bunker Roy was born in 1945 in Burnpur, Asansol. He studied at the Doon School and then at St Stephens College, where he left his mark not just as a student, but as a keen sportsperson, as the Indian Nation Squash champion in 1965, and represented India internationally in three international championships. But it was a visit to Bengal during the famine in 1965 that affected him deeply, and made him question the privilege he enjoyed. After college, Bunker rejected a prospective career in the private sector to work in rural India. After a few short assignments, he moved to Tilonia village in Rajasthan, where he began working on water issues in that very drought prone region. In 1972 Bunker set up the Social Work and Research Centre, and their work expanded from water and irrigation to include broader issues such as empowerment and livelihoods. The Social Work and Research Centre, now called the Barefoot College, is built on Gandhian principles of practicality, local indigenous knowledge and self-sufficiency. The impact of the Barefoot College is difficult to quantify, and goes well beyond the thousands of rural women from across the world who have been trained as solar engineers, to include innovation in water, energy, livelihoods, education and sustainability.

Bunker Roy is in conversation with journalist and curator of Ahimsa Conversations, Rajni Bakshi.

RAJNI

Hi Bunker, so good to see you.

BUNKER

Hi Rajni, good to see you too, after so many years.

RAJNI

Especially after COVID you are looking good.

BUNKER

Thank you – for once someone is saying I’m looking good, otherwise everyone thinks I’m looking malnourished. I should know why people are saying that. So I have lost twenty kilos. I could have done it in a better way but that’s okay now.

RAJNI

Yeah, but still very good to see you back in action. So Bunker, you have often talked about the impact of the Bihar famine on you as a very young person. I think you may have been still in college when you went and saw for yourself what a calamity that was, and how it shaped your life. But why rural India with your background, with your elite education and your class background? You could easily have sought to be relevant. You know you have spoken about wanting to give back. Why in villages did you want to give it back?

BUNKER

I went to the Bihar famine in 1965. And that was out of sheer curiosity because I didn’t know what Bharat was like. Had no idea, I wasn’t exposed to anything like that. And I had felt I had sort of a closeted existence. I didn’t know what really India was like. So at that time, Suman Dubey said, “Why don’t we go down to Bihar?” Because he knew-

RAJNI

Am I right? You were both students at Doon?

BUNKER

Suman is senior to me. Suman was Rajiv Gandhi’s friend, same classmate and they were 1959 in Doon School. I was – in 61, I left. He left in 59. So, Suman said, “Why don’t we go down because here we have a colleague called Kumar Suresh Singh who was the DC of Palamu. Very nice man, very gentle, he said, “Why don’t you go and do a survey of some villages in Jainpur block?” And so me, Suman, and another English professor called Brijraj Singh came with me. And Desmond Doig from the Junior Statesman- if you remember Desmond, covered us in the Junior Statesmen in 1971. All the 3 of us went and did some surveys of starvation deaths and what is happening there. Big shock because I had no idea there was a part of India that was going through this.

It was a very traumatic experience for me, very traumatic. I still think about those days in the Bihar famine. And I said, “What am I doing here? I’m getting the best, so-called best education and I can’t do something in the villages of India.” So that’s when it sort of sparked in my mind- I would like to do something.

RAJNI

But how did you find Tilonia? Because you had no connection before that with Rajasthan if I am not mistaken.

BUNKER

So there I was in 1967. Indian National Squash Champion.

RAJNI

I think you were travelling abroad also to represent India.

BUNKER

New Zealand and Australia. And there I was. And so there were jobs coming. All over Grindlays Bank, corporate sector.

RAJNI

That’s a really funny thought, Bunker. If you had been a banker, with the pinstripe suit and all that.

BUNKER

Horrible thought. But, the first job I got in a village was with Catholic Relief Services. They gave me a project for deepening 500 wells in Ajmer district and that is my first exposure to Ajmer. And for two years, from 67 to 69, I was digging five-hundred wells for the CRS. The CRS had got money from the USAID to do this work. So when I arrived at the Catholic Relief Services office, which was in the Cathedral, Roman Catholic Cathedral, Father Albert Cook said, “You can live here and commute from here up and down.” And I said, “Father, but I’m going to be getting some money from the villages, so may I deposit it with you?” So he said, “Yeah, sure, because I’m not doing anything for free.” So I started. And then, all of a sudden, rumours started spreading saying, “What is this Hindu doing?” You know, work with CRS. That was 1967. And they couldn’t figure out why I had been asked to do this.

So all of a sudden I saw mysterious gifts coming into my house. You know, a little shirt here, little kurta there, a little… . I said, “What’s happening, Father? Why am I getting all these gifts?” They said the Christian community has taken a decision that you must be an orphan. Otherwise you wouldn’t be… . When I heard that, I went and told my Mother – clipped British accent, very, very posh, very, very strong, very, very snooty, I said, “You better come and hot foot down here and show yourself because otherwise they think I’m an orphan.” So she came down and everyone was a bit… . “Mother?” I said, “Yes.” I said, “She is the one who is my mother.” So that deeply disappointed them that I wasn’t an orphan, I was a Hindu. But I completed the work and then I went back to the Father and said, “Father, you know, I collected a bit of money, and it’s USAID money and the auditor’s here. So please let us see where the money is.” He said, “Come, I’ll show you son, where the money is. So he took me into the church and said this is where the money has gone.” He went and floored the whole church with that money. And I said “Father, but that was not allowed, that’s USAID money, you can’t floor your church when you feel like…”, but he did that. Anyway, the damage was done. And I was hauled up for embezzlement. Because they said the money was your responsibility and you didn’t-

RAJNI

Because this was on paper, it was in your charge.

BUNKER

So I got fired by CRS by Catholic Relief Services 1969. But by then I had gone to many villages all over Ajmer district. And there was a chap who was with me who was a driller, his name was Meghraj. And Meghraj taught me everything about drilling, compressors, rock drills, explosives, how to put it in and so on. That was a great opener for me. And then Meghraj says, “You know there is a small place called Tilonia where I come from. Why don’t you come and have a look at it?” I said “No, no, I am not interested. I don’t know what it is.” He said, “Aajao saab, ek minute ek din toh aajao”. I said alright, so I went there, saw this village of Tilonia.

He said, “There is this TB sanitorium which is lying there.” It was taken over by the State Warehousing Corporation. All full of fertilisers. So he said if I want to work better, I can take over this campus. Which was forty-five acres, all buildings- heritage buildings, old buildings. I said sure, I said I will try and find out if I can get that in my possession.

So then I went to, you know, as they say, it’s not know how, but know who. So then I went to Jaipur and chief security officer that time was Mohan Mukherjee who was distantly related to us. There was a mad, mad bureaucrat called Vinod Pandey who was the development commissioner. I said, “Saab I want to start working there.” He said, “You are from St Stephens. You guys don’t last long so I’ll give it to you for a year.” I said, “Please give it to me for a year and give it to me for ₹1”. “₹1 lelo but you won’t last long.” I said, “Okay, but give it to me for one year and for ₹1”. He gave it. Then I had to get the endorsement of the community.

So there was a temple halfway up the mountain in Tilonia where there used to be a priest there. The whole community elders said “Saab yeh vishwas hai toh aap jaaiye dekhiye.” I said, “I don’t believe in all this.” He said, “Nai nai aapko jana hi hoga baithna hoga sunana hoga kya kehte hain.”

The priest said, “You will not last long.” The whole community said, “Oh dekhiye kya kah rahe hain aap, you can see in the future.” I said, “Well I can see the future, but I want to stay bit longer here.” He said, “You won’t last long.” Okay. The endorsement of the community was not welcome. Priest had it all. Fortunately, the priest ran off with some silver. I said, “Dekhiye saab, after six months he went and ran off with some silver.” I said, “Look, these are the priests you are looking at. These are the priests you are depending on.” So after that at least I got some peace and quiet to do some work. But there was a forty-five acre campus, twenty-one buildings, all lying deserted and I said what am I going to do? Yeah, how am I going to fill this up?

So the first one who walked into the door was a gentleman called Ram Baba. Distinguished harijan. Beautiful face, perfect poise. He said, “I have come here to work with you.” I said, “Why, what is your claim to fame?” He said, “My grandfather built this place. And whoever has come to this as the new owner. I believe you are the new owner. You’re a little chit, but you are the new owner, so you give me a job.” So Ram Baba got the first job of Tilonia and-

RAJNI

And he was of Tilonia village?

BUNKER

He was of Tilonia village.

RAJNI

From the Harijan tola.

BUNKER

So two of us were trying to – and our first issue was water, always Rajasthan, water. So we did a survey for the Groundwater Board of 21 of 110 houses for water. Did a very detailed geological survey of water. By which time I had also spread the word around that I was looking for people who joined me.

So we had an emblem which was designed by Madhur Kapoor. Very great designer. He designed the logo that we had was – farmer and professional. So we attracted a lot of people from the urban areas to come and join us as professionals. One was a geologist, one was the soil scientist, one was just interested and some of them happened to Bengalis. So they had heard about us and they’d read the Junior Statesman. The Junior Statesman gave us wide coverage.

RAJNI

But how are you feeding everyone? I mean, how did you raise money for all?

BUNKER

Mrs Roy.

RAJNI

She was already working?

BUNKER

She was already in the Indian Administrative Service.

RAJNI

That’s an important thing we missed. How did you and Aruna meet? Many people want to know and they never got the answer to this.

BUNKER

She didn’t recognise me for one year. We were both in the same class doing English Honours in Delhi University. So she didn’t recognise me. Someone pointed… . I was pointed out to her saying that this guy is interested in you, because he is always looking at you all the time. All these girls are gossiping away together. So that’s the first time she recognized that I existed. This is in 1966. And then 1967 I left the university, but I still carried on by seeing her. And then she got into the service in 1968. I still kept writing letters to her. So finally in 1970 she agreed.

RAJNI

So Aruna’s salary was covering some of this?

BUNKER

All. All. Because I had no money. So I said, “Where should I raise money?” So then I got to Sarkar, who was the principal of St Stephens College and he was the president of my board when I registered it. So Sarkar said, “Go and speak to Tata Trust. Because Tata Trust might give you some money.”

There was a Joint Secretary called Chandiramani who used to look after Tata Trust in the 70s. And Chandiramani and Old Man Choksi. Professor Choksi who was alive then. Professor Choksi said, “Give me ten seconds.” He said, “You are from St Stephens college? Sarkar recommended you, so you must be alright. So we will give you, we will give you a bit of money to start.”

RAJNI

So the Old Boys Club has its uses.

BUNKER

Ohh yes yes yes. No question. Old Boys Club has its uses all along, all along, not only there. So, Chandiramani said, “We’ll give you a princely sum,” at that time, “of ₹20,000 to start the organization.” So the first donation I got was from Tata Trust of 20,000. So we started doing the groundwater survey and we covered 110 villages. But then you know every organization must go through a series of crises. You can’t have an organization that has no crises.

We started in 1972. Aruna resigned from the service in 1974 and joined me. And with her administrative experience, she wanted to bring in some systems and management systems into place which all these professionals hated. They didn’t think this was a good idea because you know it will be a bit more professional. So that was the first crisis- when Aruna came and tried to bring in some systems into place and lots of people resented it. So most of them left.

First lesson, never depend on professionals from outside, urban professionals from outside. Always develop the capacity and competence of people from within the organization first because they are the ones who will be there to stay forever and ever. So that was the first lesson I received and it’s helped me up to now. Because I think we must develop the grassroot leadership. And and depend on them to carry the organizations.

The second thing I learnt was that there was a difference between literacy and education. You know what Mark Twain said, “Never let school interfere with your education.” School is where you learned to read and write. Education is what you learned from a family environment and your community. So I felt that we must distinguish the two, we must not put them because when people say, “Arey Saab they are uneducated.” I said, “No, please, they are illiterate, but they are not uneducated.”

RAJNI

When did this become clear to you, Bunker? Because this, I think, is the key turning point when you realise that you were there to learn from the people rather than to teach them. So can you kind of explain how this came about?

BUNKER

At that time we started three experimental schools under the Center for Educational Technology. and the experiment was to take people from the village and make them into barefoot teachers without the educational qualification and certification. That is how it started.

[AUDIO DESCRIBING BAREFOOT COLLEGE]

BUNKER

It started dawning onto our psyche that there is a difference between literacy and education and we shouldn’t give too much, shouldn’t give too much importance to certification. Especially in rural areas. So it was a breakthrough for us.

So that was the first crisis that we went through. The second crisis was…there was a chap from the village we hired. And we found he was embezzling money.

So I fired him in 1976. In 1977, he became the MLA of the area. And he started shouting and screaming in the state assembly, “Lakhon rupaye ka durupayog ho raha hai, gulcharrey udana wale IAS officers ke adda hai, ye aapko janch karwana chahiye,” all shouting and screaming. So the Bhairon Singh at that time was the Chief Minister of Rajasthan-

RAJNI

That’s Bhairon Singh Shekhawat.

BUNKER

Shekhawat. Bhairon Singh called me and said, “Saab, I’m sorry, ek inquiry hamein bithana hoga.” I said, “Saab, humne galti kya kiya?” He said, “Saab MLA chilla rahe hain, khilaaf bahut bol rahe hain, so you have to go through this inquiry.”

I said, “Alright, go through this inquiry.” It was a chap called Kailash Meghwal who was the minister who was asked to conduct the inquiry. So he sent a gentleman called Mr Agarwal. Mr Agarwal came and said, “Saab I want to put my cards on the table.” I said, “What’s happened?” He said “I am going to send a negative report to you before you even start.”

I said, “Why?” He said, “Meghwal called me and said ‘aapne sahi report diya to aapka kaam ho jayega.’” So I said, “What?” He said, “I want to transfer my wife from Ajmer to Jaipur. And I have to give this report.” I said “Agarwal Saab, aap bhejiye jaroor. Push kijiye. Aap likh lijiye dikkat nahi hai. Don’t worry, don’t worry, please conduct the report.” The report was deadly against me. And at that time there was a chief secretary called Mr Bhanot. Mr Bhanot said in 1979, “You will have to leave Tilonia because the enquiry is against you.”

This was in June 1978. 1979 1st January you have to leave. September, I get a letter from the World Bank President McNamara saying, “I want to visit Tilonia.” So there is a private visit. So I went with that letter to the Bhanot and I said, “Saab dekhiye, aap toh hamein nikaal rahe ho but World Bank president wants to come and see Tilonia.” “Arey how do you know him?” I said, “I don’t know him, he must have selected (at) random to come.” “Have you got electricity?” I said, “No.” “Running water?” I said, “No.” “Where is he going to sleep?” “On the floor,” I said. “World Bank president sleeping on the floor? Is that? Look at the image of Rajasthan!” he said. “He wanted to see how the rural poor live, so I am going to make it as rural as possible for him.” And he didn’t come alone. He came in (with) “Mac” Bundy, who was the national security advisor to President Kennedy. So both these distinguished Americans slept on the floor in Tilonia and they loved every moment of it.

I don’t know if you have been to Tilonia, but there’s a road from the National Highway from Patan to Tilonia. There’s about a seven kilometre road. Sixty cars were piled up there on that road.

RAJNI

Their entourage?

BUNKER

So I told Bob, I said, “Please, half an hour, just open it up because you know, I have to survive in this place.” World Bank President’s face came down. No longer Bob McNamara, World Bank President. And you know, these people, are like, they come with files, chamchas all over the place, sixty people coming. So Bhanot says, “Saab there is a 200 crore proposal, in the hands of World Bank, which we haven’t heard of. Can you tell us what happened to the proposal?” You know, cheapy things to do. So Bob said, “You know, only files over 500 crores come to me, so I haven’t seen your file.” Matter stops right there. Khatak se it went down. There’s nothing more to say because you haven’t seen the file. But he said something to me, which still sticks to my mind. He said, “Look, if you can’t make your point in one page, then 30 pages won’t make a difference. If in that first page you can convince me I will be out for it.” Still stuck to me what Bob told me there.

Then Mrs. Gandhi came back into power in 1979 so I’m still here.

RAJNI

Yes, yes indeed. So now about the emergency, did that affect you and the life of the Tilonia endeavour in any way?

BUNKER

No no too far away. I think Mark Tully came in 1976. And he… . And the first thing I said, “Mark, please don’t ask me about the emergency.” But of course, the first thing you said, “What do you think about the emergency?” being a journalist as he is. I said, “I would like to keep this part of my life separate from the work I’m doing in development work.”

RAJNI

This part meaning the political? Your political convictions?

BUNKER

Yeah. Because I didn’t want to mix the two. Because then it becomes complicated and you can’t unscramble that egg at all. So I kept away from the political scene for last fifty years. Because I was always associated with the Doon school, and St Stephens college, I couldn’t get that out of the mind of lots of people around. Bureaucrats, politicians all said, “Yeh toh Congressi hai.” I said, “I am not a Congressi.” But because I went to the Doon school, they felt that there was some… .

MUSIC

So in 1967 when I was digging wells, as soon as I came out of one of the wells, there was a cop waiting outside on top of the well saying, “You’ve been arrested.” I said, “What’s happened?” He said, “You haven’t answered the summons that was issued to you.” I said, “What summons?” He said, “Didn’t you get this summons? You were being summoned by the district collector and you didn’t answer four summons so you are arrested. Come on, the District Collector wants to see you.” So in my bedraggled well-digging clothes, I was produced in front of the collector. At that time I thought I better speak my King’s English, otherwise I’ll be in big trouble.

So I said, “Why am I here?” He said, “Ah? You speak English?” I said, “Yes, I do speak English. But why am I here?” He said, “ You haven’t answered the summons.” I said, “Well, I have answered the summons… . I didn’t know what summons to answer to because I didn’t get it.”

“Where you from?” I said, “I am from Delhi… oh… St Stephens College.” “St Stephens College? My college! So you couldn’t have probably done that.” That was Anil Bodia, my first exposure with Anil Bodia. So the whole thing… . I was really grateful that I went to St Stephens college in my earlier years. So all along the way, I’ve had these crises. And as a result of us managing to survive, we have become stronger as a result, because we have really worked for the very poor people.

RAJNI

But Bunker, is it, when you say that you have become stronger as a result, could it be that the second and third tier of your organisation were also involved in overcoming and addressing these crises? You are in a leadership role and yet there’s a very palpable sense that I get when I observe the people around you, your team. Of everyone feeling very much an authority in their own right. So how did this whole dynamic come about?

BUNKER

You are jumping twenty years, Rajini, because at that time in 1979 when we went through this crisis, we were a very small organisation, but the selection of the people who worked with us was deliberate. We only choose schedule caste, schedule tribes, OBCs and they were not powerful enough to buck the higher castes and the Rajputs and the Brahmins and Jats. So when it came to a crisis that we were facing, they were in the background. They would help us quietly, but they wouldn’t come out in front and shout and scream against them, because that was a completely different situation there. And as a result of us investing in such people, it’s been a great leveller for us because those people stood by us even after the crisis all along.

RAJNI

What was that value frame which you applied when you selected such people or, you know, build this team? What were some of the key values that you looked for?

BUNKER

Definitely anyone working with us in Tilonia would have to work on minimum wage. And the highest and the lowest ratio would be 1:2 – the highest and the lowest. And we would self evaluate that time – not anymore – but that time when we were growing, we would self evaluate ourselves about our performance and about our contribution to the organisation and we would give each other points – honesty, integrity, cooperation, innovation. Out of hundred points, three was given to your educational qualification. It didn’t matter whether you are illiterate or not, but this is your contribution to the organisation.

That made a big difference because I lost all my points because my community contact was zero, so my salary was somewhere in between. So this, they all felt that I had also to be judged. Can’t be only the staff because I was a part of them. So that made a big difference – that the salary I was getting is much less than lots of people in the organisation.

I mean, Gandhi was almost dead in many parts of India. So we said simplicity, austerity, honesty – all very important for us and we have to abide by that. We have to have a code of conduct for that. And that we laid down very early in life.

RAJNI

But laid down in a participative manner?

BUNKER

Very participative, very participative. Very open, very transparent, very accountable.

RAJNI

So it didn’t feel like there was a politburo that was handing down these values?

BUNKER

Aruna Roy made sure of that at least. There’s no politburo at all and I was slapped on the wrist many times. That was good, but that gave us a lot of confidence. That this was a society which not only worked with the poor, but also set an example of how we should work with the poor. And that helped me a lot in the Planning Commission when I was there.

RAJNI

That’s in the Rajiv Gandhi administration?

BUNKER

Yeah. In 1984-83, Rajiv Gandhi came back into power as Prime Minister and he asked me to join the Planning Commission to help him form a policy for the Voluntary sector for the first time for the 7th Plan. At that time, of course, Vinod Pandey, Debu Bandyopadhyay all were in Secretaries to Government of India. And they gave me a mandate.

They said, “Write me the first policy statement of the voluntary sector for the 7th plan.” And I said, “I hate this word ‘NGO’ because there is a negative way of defining positive action.” So I thought, “voluntary sector,” would be much better. Now it’s become more respectable, we’re calling them CSO. But at that time, the voluntary sector stuck. So I went about, I said… I told Rajiv, “I will only take ₹1,” because I had to sign the Official Secrets Act, “so I will take ₹1.”

“Okay.” So I started. Wrote the policy statement of 4 pages. I went to Somaya – Somaya was then the Secretary of the Planning Commission. Somaya said, “Who do you think you are? You think this will ever pass? There is a way that the voluntary sector writes a policy paper. This is a government 7th Plan document. I mean, where – which world are you living?” I said, “Mr Somaya, I hope you don’t mind if I try.” He says “You can try whatever you want, but then this will never be accepted.”

Same night, by sheer chance, I was having dinner with Rajiv. Rajiv said, “What’s happening?” I said, “You’ve got a very major problem here because they are not accepting what I have written – four pages only.” He said, “Show it to me.” I showed it to him. He said, “Looks alright Bunker, what’s the problem?” I said, “Please speak to the man on the other side of the table over dinner.” Manmohan Singh, Deputy Chairman.

He said, “These four pages seem to be alright, why is it being rejected?” So Manmohan Singh said, “If you accept it, then I will accept it.” He said, “I accept it.” I said, “Hold it, I don’t want it in the chapter on Public Cooperation, which is a dead beat chapter. I want this chapter in the Rural Development chapter because you are talking about rural areas.” “Accepted.”

Next day, Somaya – livid. He said, “You’ve stopped the whole 7th Plan document from being printed because your four pages is going to be in the rural development chapter.” I said, “That’s what I told you, I’m going to try.” So it became the first policy statement.

In that there were two major points that were included. One was that voluntary sector must decide on a code of conduct and that code of conduct cannot be decided by government. It has to be decided by the voluntary sector. And voluntary sector… . That code must decide how you behave yourself with your communities and how you behave with government. That code has to be done. So there was a national debate from 1984 to 1988 on this code of conduct which split the voluntary sector right down the line.

RAJNI

Yeah, yeah, you appeared as Darth Vader, I remember.

BUNKER

Absolutely, absolutely. I was a public enemy number one, I loved it! Because the larger, bigger organisations are against the code, the smallest groups are for the code. So that was a very big… big debate, the first debate of its kind on the voluntary sector and the code of conduct today. So I think that was one contribution that I did to the government while I was in the government.

RAJNI

So Bunker, going back now to Tilonia and the next phase which emerged which I think we can call the “Solar Mama” phase, I mean, you did it long before solar was fashionable. And what are the key takeaways from that experience which you would highlight here that give us a sense of what are the possibilities going forward on the positive side of the technology story? Technology and people and democracy all three together.

BUNKER

We have two campuses in Tilonia, both are fully solar electrified. We have three-hundred kilowatts of panels on the roof for the next twenty-five years. I have no problem with power as long as the sun shines. I have visited about sixty countries around the world – over sixty – and thirty-six of them in Africa. And what do you see? You see very old men, very old women and very young kids in the village. All the youth have gone. They’ve all left looking for jobs in cities. So… brainwave! Why not train women to be solar engineers from these very villages which are inaccessible? Away from the grid and there is no… and they are wasting $10 a month on kerosene candles… .

RAJNI

What year was this Bunker? This brainwave?

BUNKER

1997 maybe. So I said, “Why not train women? And even if they are illiterate, so what? Let’s see if we can train them to be solar engineers.” So we started with Afghanistan.

I went to Afghanistan. And we chose three women to come to Tilonia. And the women said, “I can’t go without the men because they won’t allow us.” So three men also came with them. Six months of hell for them because it was in the heat of summer, but they became solar engineers. How did we make them solar engines? By sight and sound. No written or spoken word. We have a manual, which is only pictorial, where you can learn how to be a solar engineer just by following the manual in six months. Which means that you can fabricate, install, repair and maintain solar systems and solar lanterns in six months. And the beauty is that anybody from anywhere in the world who is illiterate woman between thirty-five and forty-five can become a solar engineer.

[AUDIO OF SOLAR MAMAS]

BUNKER

So then I went to the Ministry of External Affairs and I said, “Under India’s Technical Economic Cooperation, why don’t we have a collaboration?” So in 2008 they declared us a training institute – the only voluntary CSO organisation among the forty as the training institute. So we trained forty women every six months since 2008, and as a result we have about one-thousand-seven-hundred women from ninety-seven countries who have been trained as solar engineers.

When the Prime Minister heard of this, he wanted to meet them in Tanzania. So in 2016 he met the thirty solar Mamas, from all over Africa, in Tanzania, and he called them, “Solar Mamas.” So that’s how the Solar Mamas stuck to the Prime Minister who called them, “Solar Mamas.” Today, we are thinking that it has become a… I mean, it’s been established that you should send me any woman from any part of the world who is illiterate from a rural village. We can train that woman to be a solar engineer in six months, which I have done from the Pacific all the way up to Chile.

RAJNI

And the program is still running.

BUNKER

Still running. And it’s been a success story all the way. When President Macron came to India in 2018, the ministry asked us to get the Solar Mamas to Delhi and welcome Macron. They sang, “Hum Honge Kaamyaab, We Shall Overcome” in Hindi and English. And that Midlands Prime Minister went crazy! Hindi and English “Hum Honge Kaamyaab.’” It was really great fun!

[AUDIO OF SOLAR MAMAS SINGING HUM HONGE KAAMYAAB]

BUNKER

Sushma Swaraj was there, everyone was there. And then the Prime Minister Macron said, “No, I want to meet the Solar Mamas separately.” So we have to herd the Solar Mamas separately into a room. And Macron was there, because he spoke French, we got a Solar Mama from Ivory Coast to speak – and she spoke French and she (said), “What the hell do you think you guys are doing? I’m an engineer now. I was an illiterate woman in the Ivory Coast. And this is what you should be doing, train us to be solar engineers.”

And he turned to the Development Corporation people and said, “Every solar engineer who comes from a French speaking country, you give them this solar equipment.” And what do we give them? Not solar power plants but solar units in every house. So you decentralise and demystify right down to the household level where a Solar Mama looks after the repair and maintenance for which they get paid by the community who are already paying $10 a month for kerosene candles. Instead of that they pay for the solar unit and so now you have the first and only technically and financially solar electrified village in the world.

RAJNI

Right, but this is an insight for the macro level. You just said two very crucial things – decentralised and household based. What is stopping the world from doing this?

BUNKER

Business, business. Everyone loves this centralised system, everyone loves the solar power plant, everyone… . Today you see Rajasthan, there are Rajiv Gandhi Sewa Kendras all over Rajasthan with one kilowatt of solar panels on every house – all lying damaged, destroyed, wasted, not using it because they don’t have anyone to repair and maintain.

RAJNI

So you are saying it’s a business vested interest that is preventing this very obvious knowledge, which clearly the government is aware of, because as you just give several examples of their involvement in the program.

BUNKER

We like bash on, we are not going to stop. Somewhere someone is going to click, somewhere someone is going to say this is not the answer, somewhere someone is going to say look at these instances.

When we trained the Solar Mamas from Afghanistan and they went back, they solar electrified one one village, Badakhshan – the first solar electrified village to be done by a woman. Guess how much it cost? Bringing three men and three women to India, flying them into India, training them for six months, buying hundred-fifty units of solar panels transporting them by air into the village, solar electrifying the whole village. You know how much it cost? The cost of one UN consultant sitting for one year in Kabul. And there are seven-hundred of them sitting there, not one has solar electrified the village. It’s a shame, that the UN can’t even think of some simplified solutions like this.

RAJNI

Because their education is degree-based.

BUNKER

Absolutely. Certified-based, everything is certification. Certification doesn’t… it doesn’t establish competence at all. Not in the educational system in India, certainly not. Today, your people who are mechanical engineers, you don’t know, who never catch a spanner in his life. You have people who are head of hand pump programs… never seen a hand pump in their life. When I went to Peru and asked the head of the solar program, “Look, I’ll give you 20 parts of a solar lantern here and 20 parts of a solar lantern there. Get the man who comes from Stanford to put this together. I’ll get your grandmother who can put this in half an hour.”

He said, “The Stanford man will never know what to look at.” He doesn’t know what to do with it because it’s all theory and no practice. So is the practice man who is the one you want? And this is the educational system that we should have to push, because this is the answer to India. Not going to… . I mean the sad part, Rajini, is that I’m the only Dosco and St. Stephens college man who’s been fifty years in a village in the whole educational system. Is… . Not one person from Doon School or St Stephen’s has ever gone into a village and stayed there. This is reflection on our system.

RAJNI

What was the secret to your success in carrying the work across the world?

BUNKER

Faith. You have to have faith in the people to be able to do it. You have to show it… . It takes me two days to speak to the whole community in Africa, to send a woman to India. First of all, there is resentment, there’s hostility, there is anger saying why are you wasting your time taking a woman all the way to India? And that convincing… . That was the process of which convincing people that fears they have – they are going to be sold to the Arabs or they are not going to come back – all these absolutely genuine fears. But I see the woman having guts, absolute guts to be able to go there. Can you imagine nineteen hours on a plane? Never been on a plane in her life. Can you imagine her coming to India and not being able to speak the language for six months?

RAJNI

So in a sense it became a commitment formation exercise because you could easily have taken teachers from India and sent them across the world, but you choose to do the opposite.

MUSIC

BUNKER

Because when you have forty women sitting on one table, not being able to speak the language, all chatting away but not understanding a word because they are speaking Swahili and Spanish and English and Jolla – they had a feeling of solidarity.

In the first time, I might be illiterate, but there are nineteen other, twenty other people who are illiterate just like me. They can do it, so can I. But if I sent a trainer to Africa, it’s not the same, because you don’t get that feeling of solidarity, of staying for six months together, eating together, working together, speaking together, making friends. And they are still friends today. That is the secret of bringing them together – faith. That’s important today.

You know, when the Afghan woman went and solar electrified a village for the first time, she went and sat with the men. And the men said, “Who do you think you are? You should be sitting with the women one kilometre away.” And she said, “I’m not a woman today, I’m an engineer. And I have every right to sit with you because I’ve solar electrified your village.” Hit him between the eyes.

Everyone who goes has problems. Every woman who has come from Africa, have got all the husbands say, “You go, I’ll get myself another woman. You go and get yourself. Go on.” In spite of all these threats they go. They go there as a grandmother, come back as a tiger. They solar electrify the whole village in front of everybody. And men are in total awe, they cannot understand what we have done to this moment.

And most of them say, “Come back.” And the woman said, “No, I’m quite happy without you, brother. I don’t want… . I’m single, I like it, I’m fine. I don’t want to be married to you anymore because now I’ve got my freedom.”

So when you ask a woman in Tilonia, “What is the benefit of coming to Tilonia for six months?” “I don’t have to cook for six months. I don’t have to look after my children for six months. Husband appreciates me much more now if I go back.” All these spinoffs we don’t think of.

RAJNI

And community recognition and acknowledgement.

BUNKER

Absolutely.

RAJNI

Most important.

BUNKER

When you speak to them for first time and they say, “Arey you speak to the youth, are you willing to be trained by your grandmother?” They say “No, no, no, I don’t want to be trained by my grandmother.” But when they come back and solar electrify the village, everyone wants to be trained by the grandmother because now she is no longer grandmother, she is an engineer.

MUSIC ENDS

BUNKER

I would like to go back a bit when Aruna started… when she started the MKSS.

The major message that Aruna’s organization was giving a social audit – that you have to have a social audit. So Bhairon Singh Shekhawat was then the Chief Minister. And he said ki, “You are asking me to do a social audit, what about your husband? Are you doing a social audit? You are asking… .”

So she publicly came back and said, “You better do a social audit on Tilonia.” So in 1987, we did the first social audit of the Barefoot College and SWRC and we documented it. How you should do a social audit, how you should… what documents you should prepare and who you should speak to, and who are the committee members who should be a part of it.

And the MLA we called at that time is now the Governor of West Bengal – Jagdeep Dhankhar. But then he came and we actually managed to show what documents you must produce to have a social audit. What you get as a salary, why you’re travelling business class, who, what is the salary structure? All this happened in that social audit and we made a film. At that time I was also in CAPART, the governing body of CAPART – Council for Advancement of Peoples Action and Rural Technology – CAPART.

RAJNI

Yeah, that time it was a very large organisation.

BUNKER

It was very large organisation. So I said why not we have a social audit. This film which we are making as a social audit that all voluntary organisations actually conduct a social audit among themselves to show that they are transparent. That they have nothing to hide. So we made 1000 copies and sent it to all the ones we know who were on the governing body in the general body everybody.

Not one did a social audit. And that was a real shocker for me. I said, “What have you got to hide? What is this voluntary sector got to hide? Why aren’t you conducting a social audit? Why can’t you be courageous enough and gutsy enough to tell the community where your money is coming from? How much money is coming and for what purpose?”

So that was a big shocker for us as far as the social audits are concerned. And I think that was, that was the message which we found was very disturbing, very distressing that the voluntary sector couldn’t rise to the occasion of having this audit.

RAJNI

Yeah, that’s your external experience, but how did it change you as an organisation internally?

BUNKER

Made us stronger, there is no question. Yeah, made us stronger.

RAJNI

I mean the organisation consisted of people with very diverse levels of understanding, cognitive skills, abilities, temperaments. What kept it all together? What were some of the mechanisms of operation or of work culture – let’s call it work culture.

BUNKER

I think the key to the success of Tilonia is the fact that we had regular meetings right across the board and you couldn’t keep anything hidden and everyone had to participate.

So if you ask someone who has been for five years in Tilonia, “How do you spend your life in Tilonia?” He said, “I started as a cook and then I went into the account section and then I became a puppeteer and now I’m becoming, I am now I’m a solar engineer.” So the mobility within the organisation was encouraged.

RAJNI

How did you, because see, this is quite a big breakthrough, especially in a rural setting, I mean even in an urban setting. How did this come about? Was it a combination of your taking a stand? And a buy in from the community of activists that took shape? Because this was not, it’s not an idea that was natural to the geographical context.

BUNKER

I think it was important for the founder to have enough confidence in the people who worked with him. And the founder had to give the space for people to make mistakes and learn. That was a very important part of it. So when someone made a mistake and said I’m sorry, I said, “Doesn’t matter, you try again because it doesn’t matter if you fail. There is no such thing as failures, just that it didn’t work out.” So I think that was very important to put into the people’s head that don’t think of anything called failure. There is no such thing as failure. It’s just that it didn’t work out and you try again. So we gave them the space and we gave them the wherewithals to be able to try again.

We would, in fact, push them out of Tilonia to start new organisations. Now there are twenty-three organisations in thirteen states of India who are on their own. Registered themselves. They have their own organisation and their own board raising their own money. And I said you cannot use Bunker Roy as the name because our job is to make you feel the confidence to be able to start a new organisation and we will support you for the first two years and then you’re on your own. Yeah. And that happened. So I was against this whole thing about Harijan Sevak Sanghs and SEWAs.

RAJNI

Why?

BUNKER

If I started a Harijan Sevak Sangh office in Orissa, why should I call it a Harijan Sevak Sangh? If I started a SEWA office in UP, why call it SEWA? Call it something else. Doing the same work as SEWA, but SEWA is your parent organisation. SEWA is your parent organisation. They grew out of SEWA and SEWA’ll always support you from the back always. But at least have your own identity. Your own identity is important and it cannot be latched on to someone like me. So I said you cannot use Barefoot College, you cannot use SWRC, you have to have your own name.

RAJNI

Bunker, what is then, if we now think of the larger society India as a whole, what is the possible theory of change that emerges from all this experience? I think one of the underlying assumptions of your work was that at least it looked like that to all of us from the outside, was that this should automatically start being copied, and as you have just described, it did in several places. Yet, these approaches have not informed and transformed the country as a whole, and I’m saying the collective voluntary sector. So how will that happen?

BUNKER

Rajni, a simple solution is the most difficult to implement. There is no urban solution to a rural problem. There is a rural solution to a rural problem. We haven’t even explored that. We are always thinking that has to be someone from outside to actually bring in a solution, which is a myth. It has to be from below.

Gandhi has to be bottom up, has to be summoned from below to be able to carry this through, which you have to take the people into confidence to well to make it work. And we haven’t immediately to do that. We have shown what is possible, but we haven’t been able to do that. Why is it not possible that just because you come up with the idea because there is a… I think you know the biggest threat to development today is the literate man and woman.

RAJNI

Explain?

BUNKER

They have come up with some ideas from the educational system which is damaging, which is out of control. The biggest problem with the educational system today is that you have taken courage away from the young people. They don’t want to take a risk. They don’t want to do something out of the box. They don’t want to fail as if that is going to be a reflection on them. This is the biggest problem today.

RAJNI

What about the youth in Tilonia itself, Bunker?

BUNKER

They all want to get government jobs. They all want to get into…they all want to get into the police. But our success story with the Shiksha Niketan for the last twenty years has been that we have generated enough jobs in the rural areas and not in the urban areas. So we had thanedars, we’ve had gram sevaks, we’ve had patwadis, we’ve had health workers, we’ve had all these are people who stayed back in the village and they have actually contributed.

RAJNI

But only in government jobs are there some who have managed to stay back?

BUNKER

Self employed? Yes they have. There are some people who stayed back. 70% of the several thousand people who went through our Nav Shiksha Niketan have stayed back. They are masons, shopkeepers, politicians, all these people have actually grown out of the Shiksha Niketan school that we have, the experimental school that we have.

RAJNI

But is this an oasis? Because what one reads based on many contemporary reports, is that the rural youth defines itself, its aspirations, with the metros as the benchmark, and is that true from what you see?

BUNKER

Rajni, you ask any rural youth, “Who is your role model?” Who are their role models? It’s not Gandhi. It’s Amitabh Bachchan, Shahrukh Khan – all these people are role models. What have they done? They do not look up to people who are simple, who are doing some great work on the ground, who are helping communities. They are not looking up… . They are not role models for them, they are fools. You are wasting your time.

They look down on their parents for doing this sort of work. How can you change that? You have mass media which is bombarding them with also these success stories from the urban areas. How do you expect them to not react?

RAJNI

So what is your vision then, Bunker of the future going forward?

BUNKER

I think it has to be from the bottom. It can’t be from the top.

RAJNI

No, but the structural violence is from the top na? The structural violence of the macroeconomic system, the pillage of natural resources from the base.

BUNKER

Don’t think so much, Rajni, on this. On the global macro side, I want to see whether we can get a ration card for someone properly. I want to see if you can get some food, food to eat. This is my major problem today. The macro doesn’t bother me at all. And I’m not even interested. I want to see that within the area that I’m working I can improve the quality of life of people. Why? Because I want to see that they don’t migrate. We have managed to reverse migration by the thousands because people have lived back in the village. That is important. For me, the macro doesn’t matter at all to me.

You know His Holiness came to Tilonia.

RAJNI

Dalai Lama.

BUNKER

Yes, His Holiness, the Dalai Lama came to Tilonia. He said something very profound. He said, “Now that you showed the Barefoot College working in practice, let’s see if the experts can make it work in theory.”

We are doing everything wrong. You are not following the classical theoretical concepts of development, and yet we are making a difference. Because why? Because we are depending on the human side. It’s the human being we have to change. This is the human being who will change. You will make the difference, and that is your job. Your job is to change the human being from within.

RAJNI

So Bunker, in closing, on this high note what is the plan for the rest of your life?

BUNKER

I’ve got so many non-electrified villages to solar electrify. I got so many Solar Mamas who want to come. It’s an, I mean south of the equator. When people say, how do I select the… how do I select the country?

I say I go to the UN human development report and I go to the last country and I work myself up. So the last country at that time was Somalia. Democratic Republic of the Congo, they’ll all come. They’ve all come. So if I can prove, if the Barefoot College can prove that this model is replicable anywhere in the world, what can we do?

RAJNI

And then what about after you? What happens to SWRC? What is the succession plan?

BUNKER

There is a team in place. They are hesitant, but there is a team in place. Now the team is much more interactive because now we have SBI fellows as well as the people on the ground. So there is a professional.

RAJNI

But the SBI Fellows are transient.

BUNKER

Some of them stay forever. There are one or two people who have been to Oxford. And they say that whatever I am learning in Oxford, I am learning in Tilonia. So why do I have to go to Oxford to do that?

RAJNI

Every generation produces some young people who step out of the beaten path and you know, go in search of their Tilonia, okay? Whether they do it in technology, whether they do it in health, education, so many fields and same is happening now. What are some of the key, you know, kind of lessons from your life that you would share with them? With the dreamers, with the, you know, restlessly innovative, want-to-make-the-world-a-better-place youngsters.

BUNKER

I tell them, you get into a train and go fifty kilometres outside your city and get off that station. Small one – and see if you can survive for one year without money, without ideas, without projects, and see if you can adapt yourself to the lifestyle. Because you are used to a hundred miles per hour lifestyle, all of sudden you go to a village, it is zero miles per hour. Can you last? Can you adjust? Can you adapt?

You can’t? At least you gave yourself a chance, that you can do it or you can’t do it. That is very important for us. I am always hopeful because when the youngsters come to Tilonia, I see a bright spark. They are lasting out. I think you get admiration for them.

RAJNI

Thank you so much. Thank you.

HOST

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.