E1

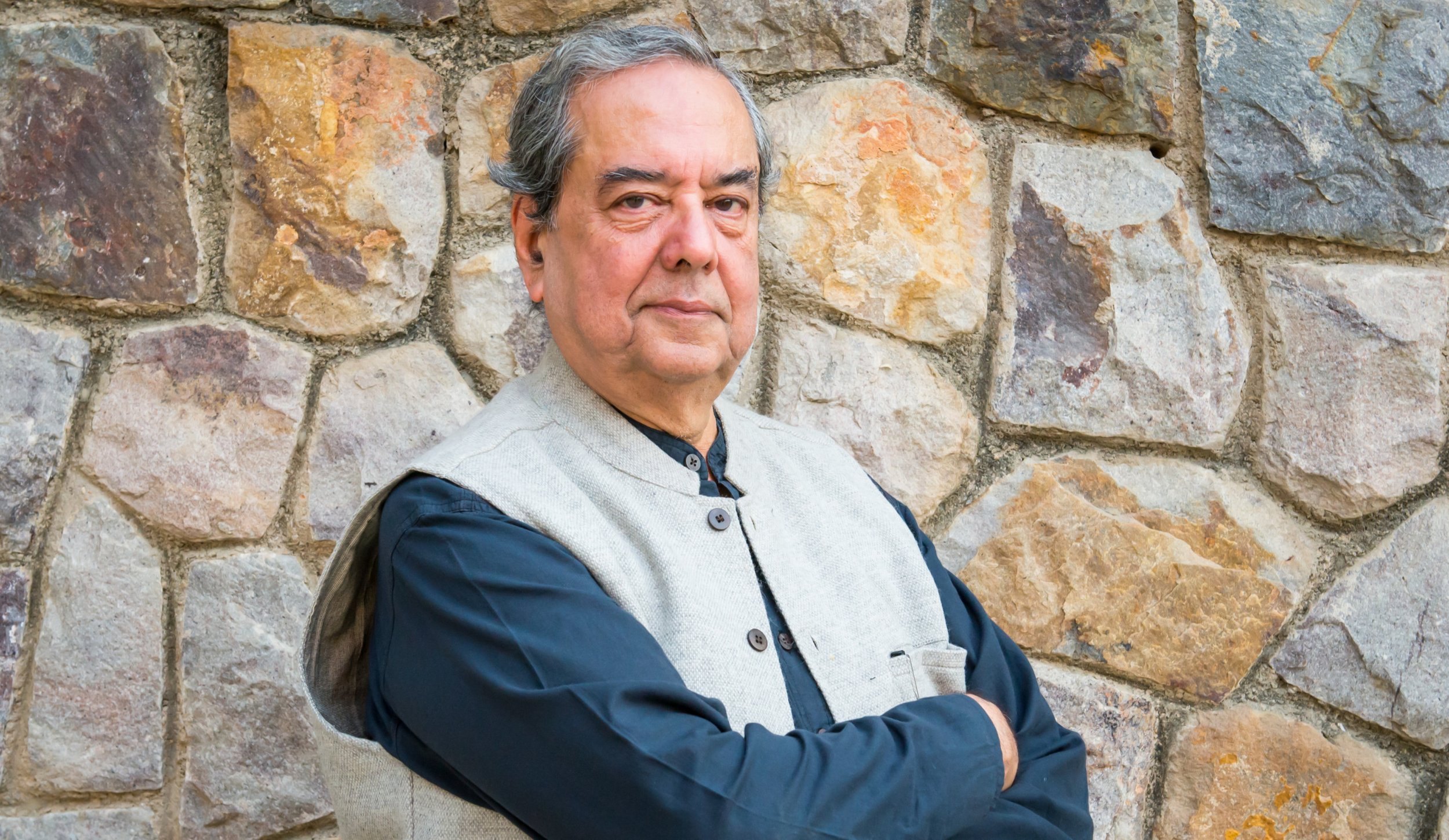

Dr Ashok Khosla: It’s possible to do good, and good business

In this first episode of Grassroots Nation, we meet Dr Ashok Khosla, an environmental visionary, a pioneer of sustainable development and the founder and Chairman of Development Alternatives. Dr. Khosla began thinking about the environment and our collective future well before climate change became something we hear, discuss and worry about on a daily basis. A man with a deep love for the job, a wry sense of humor and an absolute technophile and self-confessed gadget geek, Dr Ashok Khosla is in conversation with his longtime colleague and friend, the CEO of Development Alternatives, Shrashtant Patara.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Dr Ashok Khosla

An experimental physicist by training, his early memories were marked by partition, and as a young man Dr. Khosla went on to study science, first at Cambridge University and then at Harvard University. At Harvard, Dr. Khosla worked with Roger Revelle, one of the pioneers who studied global warming and helped design and teach the first undergraduate course on the environment. He’s built global institutions that have been at the forefront of environmental work, he’s shaped and designed India’s early environmental frameworks that set the country on course for sustainable development.

Shrashtant Patara

Shrashtant Patara is the CEO of Development Alternatives and Executive VP, Development Alternatives Group. An architect by training, Patara has been with the Development Alternatives Group since 1988. Read more about his work here.

My hope comes from reason thinking about what we could be doing, and my hope comes from the fact that organizations like ours will have an impact on that thinking. So the hope has to be founded in some reality, a real, potential for achieving it.

Dr Ashok Khosla

Reading Resources:

- Roger Revelle’s Discovery of Global Warming International Environmental Information System INFOTERRA by UNEP Limits to Growth by Club of Rome World Conservation Strategy by the IUCN

Archival audio used in this episode:

- Integral India: Four Days in 1947 by Indian Diplomacy (CC BY 3.0) 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Part 1) by MDJarv 1992 Rio Earth Summit Adverts by ricjl (CC BY 3.0) IBM Computer commercial 1986 by jlehmann

Note: This episode is produced for the ear and designed to be heard, not read. Readers are encouraged to listen to the show to get the full experience. The transcripts are meant as support documents and may not include inclusions from the day of recording and may contain errors. The audio version is the final version of the show. Ignore the timestamps mentioned. Ignore grammatical errors.

INTRO

[THEME MUSIC]

HOST

When we think of social leaders, we think of a certain kind of personality.: People who have dedicated their lives to demonstrating moral leadership, building institutions, leading social movements and whose work has been instrumental in strengthening the fabric of Indian society, our samaaj.

But what are their stories? How did they come to this path? What events shaped their perspectives? Who influenced their choices? And what are they working on now?

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

These are individuals whose work has been instrumental in shaping Indian society. If we live with a sense of possibility today it is because we stand on the shoulders of these giants.

In this first episode of Grassroots Nation we meet a pioneer of sustainable development, someone who was thinking about our environment and thereby our collective future well before climate change became a phrase we hear about daily.

[MUSIC FADES]

HOST

Dr Ashok Khosla is environmental visionary and the founder and Chairman of Development Alternatives. He’s built institutions globally that have been at the forefront of environmental work, he’s shaped and designed India’s early environmental frameworks and set India’s course for sustainable development. He also believes that it’s possible to do good, and to do good business.

Dr Khosla helped design an experimental physicist by training, Dr Khosla’s early memories were marked by partition, and as a young man he went on to study science, first at Cambridge University and then at Harvard University.d teach the first undergraduate course on the environment at Harvard University, As a young man, he worked with Roger Revelle, one of the pioneers who studied global warming, an experience he credits with changing the course of his life. He had a peripatetic life, one marked by huge achievements, but he could never shake off India, which in his own words, was in his “DNA” and it is what lead to him to return here to work on the most intractable development issues – innovation for livelihoods.

A man with a deep love for the job, a wry sense of humor and an absolute technophile and self-confessed gadget geek, Dr Ashok Khosla is in conversation with his longtime colleague and friend, the CEO of Development Alternatives, Shrashtant Patara.

PART 1

PAT

Good afternoon, Dr. Khosla. It’s such a pleasure to be with you here today. It’s not often that we get a chance to talk about the journey of development alternatives. The 40 long years over which DA as an organization has grown and the world has also changed in many ways.

ASHOK

Hi Pat, it’s the first time you called me Dr. Khosla for a long time, so I’m very honored, but I’m just as happy if you address me as Ashok in the normal way. I have had an awesome 40 years with you guys. It’s been a terrific journey and I’m so glad that we have a chance to reminisce a little bit and talk about where we’ve been and where we ought to be going.

PAT

So Ashok, a lot of the people, when they talk to us, they just cannot believe that you did nuclear physics at Harvard and then, you know, ended up setting up Development Alternatives. So how did you get to Harvard? What happened there?

ASHOK

Well, the answer to that question is to some extent, I could have dropped physics where I was no good at it.

Or I had some very deep reason to do something else. And I think I’d like to think it’s the second. That when I was very young, I grew up in an academic household. My parents were university teachers. We, at Partition left Lahore, where we used to live and go back to where our grandparents lived in Kashmir.

One evening in late October 1947, the Pakistani government sent Raiders in and they were pretty awful people. They did nasty things. And all of a sudden the lights went off because they got to the power station in Barramulla and we were left with no electricity and lots and lots of shouting outside saying “you better get out of here, you will be killed or raped and you don’t have much time”.

[AUDIO CLIP, PEOPLE REMEMBERING BARAMULLA]

And my mother had a few canisters of petrol and we commandeered the next door neighbor’s car, filled it up with petrol and started driving towards Jammu, towards civilization. And basically it was an adventurous journey. We ran out of petrol, we walked for five or six days down to Jammu, down the hills, up mountains and all all over the place and ended up in a refugee camp here in Delhi.

My father was an eminent professor. He was invited to join the Foreign Service, went off to London and took us with him. And we grew up for most of our youth in England and in Europe. What happened basically was that, it’s all about DNA really, but a DNA that evolves not just purely but genetically, but in the form of experience. And my DNA was India.

My whole being was about how I could be a citizen of my own country and be able to contribute to it from a very early age. And when I went to school in England, I fell in love with science. I was reading science, I couldn’t stop reading science, I used to do laboratory work.

I was convinced that the only thing in life was to be a physicist and to get a Nobel Prize. That was the driving force for many years. So I did that. I was in school, high school and boarding school in England, and then from there I went to College in England, where I got a degree in natural sciences.

And from there I went to Harvard to do a PhD in experimental physics. It was a great, it was a great opportunity to grow and learn. And remember that almost everything in the back of my mind was will this be useful in India?

So at that time at Harvard, I was given an opportunity by an amazing professor he allowed me more or less to do whatever I wanted. And being at Harvard, what I wanted to do was learn everything. So I went to the Business School and basically got an informal MBA and since I didn’t have a certificate.

I went to the Economics department and went to all the lectures. And I studied literature and other things too because that was fun. But essentially one day I realized at the age of 31 that I was basically indulging myself too much. It was great experience and great learning.

But I was putting off the date to getting home. So I wrapped up my luggage and my parents sent me a ticket and I came home. At Harvard, I was not only learning a lot of things I thought would be useful for India, but I was also running businesses and basically, one of the businesses that I was running was a computer data management system, and we had a big computer.

So I was really making a certain amount of money and doing something that was interesting. During the summers, I did something that no graduate student would ever think of doing, which is selling encyclopedias door to door. And that was an unusual experience, I think, in some ways, those three months, one month in each of the three years that I worked, I learned more about people, about management, about managing one’s time, and a lot of other things than I did in the whole of my Harvard studies for 10 years. So basically I was a mix of an academic and a business person at that time.

And I was making really, you know, enormous money. And I was having a great time. The one thing that I did at that time, which was very life changing for me, was to teach a course with a second professor who was also in a gigantic intellect. His name, his name was Roger Revelle, and he was the one who discovered climate change.

He was an oceanographer. He found that the amount of carbon in the oceans wasn’t matching the amount that it should be there. And he asked the National Academy of Sciences to conduct some experiments, measurements of carbon dioxide, and wrote a paper on climate change. And he and I taught a course on environment. It was the first university course anywhere in the world, and it was a very visible.

Almost emblematic course which was taken by three or 400 students. It was a big course and I was teaching sections of those and my students included Vice President Al Gore, Benazir Bhutto who became Prime Minister of Pakistan later on and a lot, lot of other people who now headline material. So Professor Revelle, who was really more a family than a professor for me because we work together a great deal, wrote to Mrs. Gandhi, Indira Gandhi saying that I was insisting on coming home and that she should help me find a job.

So as soon as I got home I was given this letter from the Prime Minister’s office saying I should meet them and she was setting up a Ministry of Environment, which wasn’t quite a ministry at the time. It was an agency under the Ministry of Science and Technology. I basically was offered the job of setting it up and running it, which is really quite extraordinary. So I was only 31 years old at the time, but, and I was not IAS, I was, you know, an outsider and so on. But it sounded like a good thing. But my entry, my re entry into India after nearly 20 odd years

wasn’t good. It was rather disastrous. I’d been brainwashed by the West and so to me, everything in Delhi seemed to be nonfunctional. And I basically packed up my bags again, my bag, one bag, and went off to Goa and became a hippie and I had a great time and then I got a call from the Prime Minister’s office saying, “I thought you were going to start this thing up”, so I decided to come back and we started it up.

PAT

Yeah, we’ve been looking for photographs from that time in Goa and we have not found any. But just to go back for a moment, was it those years at Harvard where you learned how to work, you know, 84 hours at a stretch and

ASHOK

Yes.

PAT

that’s something that’s troubled us till date because-

ASHOK

I know, I know. I’m trying to get out of those bad habits.

But being in a university, you know, the clock doesn’t work, and my lab was there all night for me to work, and during the daytime I could go to lectures and and talk to people and so on. So yes, what I tried to do when we set up DA was to give my young coworkers an opportunity to do the things that I had an opportunity to do, which was to make good use of time.

There was always some cafeteria open at night and you could go and eat, but every minute counted. So to some extent that has infected DA and hopefully for the good. But basically being a graduate student meant making full use of every resource you had, including time. Basically after that

I ran this Office of Environment, which is for five years, the most powerful job I can ever imagine. Everybody thought that I was reporting to the Prime Minister, so anything I said was seen as word from the top. And I went around stopping factories doing all kinds of outrageous stuff, which very quickly led me to an understanding of what environment meant for India?

You know, everybody used to laugh at me and say what are you doing in India? This is a poor country. What are you talking about pollution? And why it was, it was a laughing matter actually for a long time that I was working on these issues. But in a way that experience in India, those five years led to the whole concept of sustainability.

Because later on I was in a position to put that into the global jargon. And sustainability was a way of seeing the environmental issues as being tractable for a poor country. You don’t say no, you say yes, but you have to find ways in which you can get your cake and eat it.

And so, you know, in those days I had to deal with projects like the Mathura refinery, Chilca Lake, like Kashmir’s environmental issues and so on.

These are very high visibility issues and I got very deeply involved with the global environmental movements. Since I was the government delegate to all the conferences, including the Big Stockholm Conference which started the whole process. This meant that I got invited to join the UN to help set up the headquarters in Nairobi of the UN program.

Infoterra was the information program in the environment program UNEP. And basically that was the starting point of a global presence because I was all over the place. I went to 110 countries trying to get governments to set up agencies, but that also meant that I could get involved with the club of Rome, with IUCN, with the International Resource Panel, etcetera.

So when I was in back in Delhi, at the end of it all, after the UN, I set up Development Alternatives, I was still one leg in the international system. And that leg was only possible because I had huge colleagues set of colleagues who could provide me with the intellectual support to be able to influence the global scene.

I became president of the IUCN, and that’s a very big organization, scientific organization for conservation. Then I was also involved with the Club of Rome, which really in a sense started the whole environmental movement with this book called Limits to Growth, and I became president of that and varieties of other things.

Later on, I set up and chaired the International Resource Panel, which does what IPCC does for climate, it does for resources, and I headed that for 10 years. So that was a very active time during which I was in airplanes most of the time.

But it brought in lots of ideas and information and support for the work of DA.

PART 2

HOST

In 1983, Khosla set up Development Alternatives, with the vision of creating an organization that could do good business and contribute to sustainable development at the same time. His life and work are deeply entwined. He’s a firm believer in the power of the collective to solve big problems – like minded people working together. And when he speaks, his relationships with his colleagues stand out. Development Alternatives, DA as he calls it, was born during his time with UNEP where he was trying to build a business plan for a social enterprise that was also focused on innovation.

PAT

I think the first question that anyone asks when they, you know, want to know more about development alternatives is why? Why was development alternatives set up? Why did you take that step back in the early 80s?

ASHOK

Mainly because many of my colleagues and I had been giving a lot of thought to the way things are in the world and we came to the conclusion that it wasn’t the way it should be and the existing institutions were not capable of dealing with the problems the way they needed to be. I had a bunch of friends. That was a time when I was involved with the Government of India and with the UN and we used to meet in conferences and high level meetings and airports.

And instead of continuing to gripe about how bad things were, some of us decided we better do something. So a bunch of us, these two people at that time, Christian Delight, a wonderful Canadian and myself, one day resigned from our jobs, more or less on the same day turned up in Delhi and we decided to start Development Alternatives. And it’s been an amazing journey since.

PAT

I remember first having met Christian at your house, in fact in your garage, where a lot of us started working. But in all this, there must have been a point where you decided that a new kind of institution is required. So what triggered that?

ASHOK

The lack of institutional frameworks that could deliver what was needed. But what was needed, what is needed at that time and still, is the eradication of poverty. Extreme poverty throughout the world and regeneration of the natural resource base. Conserving our heritage in terms of nature was as important for us as the twin problem of poverty. These two had to be dealt with together.

And we didn’t see many institutions doing that. So we felt that this was a niche that we had to fill to bring about a different kind of a world in which people and nature mattered. We also had, in a sense, a proximate reason why we wanted to do this. And it was an internal, personal reason, because most of the partners that I worked with in conceiving Development Alternatives were driven by a sense of outrage, an individual specific outrage, that the world should be so unfair, so unjust, and, and I think that was the most important driving force, the desire to see a better world for everyone and for the long term.

The issues were so big and so complex and so urgent that we thought that the existing institutions of governance of government, international agencies of big business and even NGO’s were not adequate to deal with them. And we came to the conclusion that we needed to have a hybrid type of institution that would bring the strengths of all these existing institutions and not many of the weaknesses, together into a new kind of enterprise, which we call the social enterprise. At that time there were no such things and basically, received wisdom was that there couldn’t be such a thing. In fact, I was very privileged during the preparation of the work that led to Development Alternatives to meet a lot of very eminent thinkers and management experts.

And I even met Peter Drucker, the guru of management, and he looked at me and at that time I was a bit younger. And he said, young man, you can either make money or do good. You can’t do both. And the received wisdom was that you either did a big business and make a lot of money or you set up an NGO and do a lot of impact.

And my feeling and Christian’s feeling was that that was not adequate, and we needed the the objectives of NGO’s and governments to do good. And the methods of business to scale up, to make the numbers possible.

PAT

It’s interesting you mentioned that because the phrase or the sentence that you use ‘development is good business’ was one of the first things that attracted a lot of us at that time to Development Alternatives.

The period that we’re talking about is the mid 80s. Liberalization had not kicked in yet. It came a bit later. And you must have been among the first people who talked about using entrepreneurship markets that existed in India as the way they were, as a means of engineering change. Was it blasphemous to many that you could, you know, do the work of the government or, you know what would normally be done through charity in such a manner?

ASHOK

Certainly within the civil society sector, it was blasphemous. We got a lot of flack and we were not ostracized because our intentions were seen to be good. But frankly, our methodologies were suspect because for most NGOs and voluntary organizations, business is the enemy. It’s the cause of the problems and we were espousing some of their methods and that wasn’t congenial to the local thinking, but I would say that the logic behind what we were doing was pretty strong.

And although I’m not sure we’ve had a large number of organizations clone what we do yet, which would be a good sign of success, but there are a lot more today people wanting to call themselves social enterprises than there were at that time, yeah.

PAT

How did we get the engine up and running?

ASHOK

For us, numbers were important. Quality of change and the scale of change were both a given from the beginning. If you could change the lives of a few people in a village, I think that’s a wonderful thing to do. And we had no problem with that and we encouraged our colleagues to do exactly that. But if you were going to deal with problems at the scale that they demanded poverty and hunger and resource degradation are massive scale issues.

Then you had to match that scale with the solutions. There’s a law in cybernetics called Ashby’s Law, which basically says that the scale of the complexity of your problem needs to be matched by the scale and complexity of your solutions. And that makes sense. And so.

For us, scale was very deeply embedded and in order to do that we had two or three secrets. One was the application of good business management methods. There are very few organizations in the world that do better at scaling up than big businesses. And the second was partnerships by doing things with other people, causing things to be done by other people.

And very early in the game, probably when we were two or three years old, we got the idea that it was very much in line with Indian thinking, Indian culture, to cause things to be done. In fact, our language, our very way of speaking, embodies that. You know, it’s the only language system, the Indic languages, that have a tense called the causative, and this causative tense is a way of saying get something done as well as doing it yourself.

And you take a verb like banana to make, it comes with a causative sense tense called banwana and banwana means cause to be and get someone to make it for you. And it goes very deeply into our culture to make and share and partner. So our approach in a logo, in a slogan sense internally the way we communicated with each other is, we are trying to to go the banwana route rather than the banana route. You can either set up large factories or you can make same things in small factories which you enable through your innovations. So for us, scale is important and the means of scaling up is even more important.

PAT

For many, and I’d say most of us, you know from the time I joined Development Alternatives till date, I think this is a distinction that is often difficult to grapple with because you know, if you’re talking about roti, kapda, makaan or, you know, if you’re talking about taking care of, you know, nature, it’s it’s much more natural for someone to want to just go and do it.

I think people you know that join our organization. That’s the kind of motivation they come with. So when they’re told no, it’s not about your going and building a house for someone, but figuring out, you know, ways in which millions of people can build houses-

ASHOK

Absolutely. And Pat, the other side of that coin, is just as important. People, organizations, individuals need to get normally need to get credit for what they do and this banwana business gives credit to other people. So it’s also a matter of thinking different, about how you get rewarded. And in our case we were willing to give up that reward that you get with people saying you did this by enabling other people to do it.

PART 3

PAT

In 1986, going back now, what would it be 36 years or so, one of the things that got me hooked, this was when you would come to deliver a lecture at the School of Planning, Planning and Architecture, was the emphasis at DA on systems and systems thinking. Why have you from the very beginning. you know, thought that systemic thinking is absolutely essential?

ASHOK

Part of the reason is that I was always intrigued by systems and studied them. So professionally I was, you know, interested in application of systems thinking. But more important than that was the fact that basically, most of the issues that we were looking at hunger, poverty, destruction of soils and lands and forests, all of these had very complex intersectional causes and in order to deal with them you had no choice but to be systemic.

So we just found there is no way to get permanent solutions that were equitable, that were efficient without looking at all the parts together. So a holistic approach, systems approach to whatever we did, whether it was for water or for sanitation or for energy or for housing for example, was all embedded in an understanding of the interlinkages between all these.

There’s another reason DA, Development Alternatives is an organization that has a subtext. It has a subgoal which is not sub in the inferior sense but underlying everything and that is to build the leaders of tomorrow, the people who will be whose lives we’re dealing with and who will be responsible for other people’s lives in the future. And for young people, they have to recognize that the world is changing so rapidly that it’s no use having specific skills. If you can code computers, it’s great, you can do coding.

But the kinds of jobs that you will be doing in 10-15 years time have nothing to do with coding. You’ve got to do. And we came to the conclusion that the one skill that everyone will be needing is how to deal with changing circumstances. There’s nothing better than systems thinking for that. So we really tried to build that into our thinking because without being able to connect the dots, the kinds of changes that are taking place with climate change, biodiversity loss, species extinction, we’re going to have to live in a different world and your training in universities and schools, not just in India but all over the world, but but we’re concerned with India was really how to learn skills to do a particular thing which is of importance today, but it won’t be tomorrow and day after.

And a large part of the systems thinking, the modeling, all the tricks of the trade were critically important and that’s why we lay so much emphasis on that.

PAT

You brought the first personal computer into the country. I and a lot of other people had so much fun fooling around with it in 1986, 87, 88

ASHOK

Sure, you remind me. I mean, in 1982 when the IBM PC was first launched, I booked one and flew all the way to New York from Nairobi to pick it up.

And I was transferring to India And so I was allowed certain amount of imports and I brought, I smuggled the computer in and I was allowed to do that because the customs officer kindly took my explanation, which was that it’s a new kind of television and I brought it home. The reason that it was so important in our lives was it was the best recruitment tool that I ever had.

I mean, because of that, we call her the old lady because she was very, very important in our lives. Half of the toppers from IIT & SPA were interested in coming to work with us and we had a terrific time. So this gadget, the PC, which is terribly rudimentary, I mean, you know, it, it it was 8K memory, I mean it was ridiculous how weak it was, embodied for us not only a way of working doing our work better, but how to apply it for our work in the in the development arena.

PAT

If we may, let’s, you know, go back to those early years, you talked about hunger, poverty, land degradation. Do you do you think things have changed? 30 to 40 years down the line do those problems remain? Have they taken a different form or have solutions been found to some of them?

ASHOK

There are a few areas where there are solutions being found and being propagated in food production, in food processing and energy areas and so on, but nowhere near enough. And the result of that is that the actual problems of hunger and malnutrition and loss of resources are actually worse today than they were 40 years ago. So to some extent it is our urban perception that things are improving, but actually, you know, you and I work in the villages and we can see a great deal more needs to be done and it’s not really changed very much since we started, 40 years ago.

So I would say the answer to your very important insight is that all the efforts of governments, business, NGO’s, everybody to find solutions have still not actually solved the fundamental problems of the country, which is of large numbers literally, you know, three quarters of the country being left behind in the economy in terms of physical health, of their education, their intellectual health and in many other ways. So the answer to your question is no, we haven’t been able to deal with them at the scale needed.

PAT

Does it still trouble you that we might be two countries, that there’s an India and there’s a Bharat?

ASHOK

Yeah, very deeply. That’s really the issue. Not, not because they have different cultures, which is wonderful, but because they haven’t benefited from each other except through exploitative labor relations. There is really no real contact between them. It’s improving, but the hope in their lives, the aspirations and the actuality in their lives is a huge gap and frankly, it bothers me a lot, yeah.

PAT

The Mahatma. Gandhiji was a significant inspiration in evolving not just your approach to development, but, you know, I dare say, how to approach life itself.

What kind of values you know espoused by Gandhiji have you found important in the work that you’ve done and Development Alternatives has done?

ASHOK

Today, referring to Gandhiji as an inspiration has a, it’s a handicap because young people don’t seem to think that’s terribly relevant, and even older people.

I was on a conference call the other day and I was talking about our Gandhian approach to marketing and so on. And they found that a little bit odd. You know, even pretty eminent people. I’ve had a very variable relationship with Gandhi. I was in a boarding school in England and I had to write a student essay, one of those big, you know, essays that you get a prize for and in the graduation you get a certificate and so on.

And I wrote it, chose to write it about Gandhi and it was, looking back on it, pretty critical. I mean, I was 17. That was in, it was, what, 10 years after Gandhi had been assassinated? And frankly, I was very skeptical about his view of development as vis a vis India. It seemed to be to me, at that time when I was 17, a little bit ancient and out of reality, out of touch with reality.

However, when we set up development alternatives, it was not seen as a Gandhian institution. I didn’t see it as a Gandhian institution, but as we developed it and we, we started working with technologies and with empowerment and with the issues of Community development and so on, each one of the Gandhian concepts, from sarvodaya all the way to antyodaya and in between, kept coming up. So by the time DA was about five years old, willy nilly, we had become a Gandhian institution. You know, we were worried about sufficiency, about waste, about all the kinds of things.

You know, Gandhiji was an incredible ecologist – ecosystem person, he, he really understood he was a systems person. You know, he understood all these connections between different parts of life. And frankly our espousal of Gandhian thinking is actually from a practical point of view, not not something that is ideological because when we started selling handmade paper we were forced to think about where the money flows and the importance of local economy and impacts was a purely Gandhian thing. And you know there was this is ah-ha when we figured out what we were doing, Gandhiji had already thought about a long long time ago. So appropriate technology, you know

Chris Schumacher was a Gandhian. So a lot of our stuff that we were doing was very similar to Schumacherian principles, which are Gandhian principles. So actually we sort of got drawn into Gandhi as a practical matter. I mean it’s it wasn’t something that we got up as a religious or an ethical or a moral ideology. It was, it was obvious that that was the way to go.

Gandhiji was incredibly insightful about society, about people. And now, you know, it’s religious and we’re not very much into, so I can’t say much, but all I can say is if we have views of economics, ecology, work, trade and so on, I mean, it’s Gandhian.

PAT

Globally, you must be among the five or six people who’d actually predicted climate change and talked about the effects of climate change. Do you think the world responded too slowly to those predictions?

ASHOK

Pretty well to all predictions except ozone were slow. To biodiversity loss, It’s even slower. I mean extinction of species is growing at a rate right now that is truly a threat to human life, to civilization, to life on Earth.

But basically I was among, as you say, the first half dozen people to plant a flag for each one of these things at Rio where I was chairperson of the NGOs and subsequently look the word sustainable development was first printed in a book called the World Conservation Strategy, of which I was a coauthor. I mean, you know we took that, put it into the Brooklyn Commission where I was a member and that led to Rio Earth Summit and all of these things were known but nothing has been done about, very little has been done about them and it’s painful to see missed opportunities.

But being ahead of your time simply means you didn’t communicate it well, I guess. And I I think that’s part of the part of the reason one has to to accept that it’s your responsibility.

PAT

And yet you chose not to be an activist or to be an evangelist on these kind of issues.

ASHOK

Yeah, look, there are different ways to be activists. You’re an activist when you go out there and work, work with the self help groups and FPOs and so on. All of that is activism. And we do a lot of activism in various ways. Activism without solid thought and without solid action behind it. I think it’s been meaningless.

PAT

I know you in particular have always believed in people per say the kind of things people can do right from, you know, the woman in the village to professionals to sometimes exceptional leaders that we’ve seen in civil society, in the corporate world, sometimes even in government. Have you over these years felt that, you know, it’s been a lonely journey or do you see or did you see occasions in which you felt you know, people were actually coming together to further a cause, to collaborate to, you know, work in partnerships?

ASHOK

Well, look, the experience of DA itself, which grew to be 700-800 people, obviously showed that there were a lot of people interested and totally committed. So that is never a basis for loneliness of that kind. The loneliness one feels in a professional job is that there are less than you would wish recognition of the possibilities that your innovations can create for the country.

So there I think it’s important that we recognize that anyone working for a better world is going to be alone in many ways and not that many things. I can’t complain. I have to tell you that my family was incredibly supportive of what we did. My father’s greatest day in his life was when I resigned the job in the UN and came to work for 100th the amount salary in DA.

He basically made it possible for us to start the organization. He paid for the land, he basically, and he was not a rich person, but my whole family, my wife, my parents, my kids, they all felt that this was something that was worthwhile and I could not have done it without that kind of support from friends and from my colleagues.

So alone, being alone is a very stratospheric kind of feeling. Being alone in the universe but not locally. I mean, I think I got such incredible support from all the people we worked with and other NGOs and our partners that I don’t think that that was a real issue.

PAT

Were there moments in these 40 years when you thought it’s not going to work out or you know that we aren’t able to do enough?

ASHOK

Yes, we are certainly not able to do enough because the problem is big and that’s a feeling you can see right now still, but there was never a time when the existence of what we had to do came into question. I mean, we really had a total commitment to see it through to the end.

People used to say, “you must be feeling very frustrated”. I said “frustrated for what”, I mean, this is this is the job that we need to do, and any little success is actually the opposite of frustration. It’s the reward and it’s life giving. So yeah, you’re right. It’s a part of the DA thinking that this is a kind of privilege to be able to work on these issues in a way that makes a difference.

PAT

One of the things that has fascinated us as colleagues, you know, over these three decades and more, is that for someone who can look so closely at problems and understand them in so much detail, you also give us a lot of hope. I mean, I’d say you radiate hope. You’ve almost written the textbook of hope as far as the environment and development is concerned. So what would be your biggest, you know, fears? You’ve mentioned some of them, but then also your most prominent hopes for the future.

ASHOK

Yeah, you know, people say I’m an optimist and I’m not sure what that means because it’s not a religion, you know.

My hope comes from reason thinking about what we could be doing, and my hope comes from the fact that organizations like ours will have an impact on that thinking. So the hope has to be founded in some reality, a real, potential for achieving it. And I think most of us who are problem solvers, rather than problem explicators, have ideas about how things can be different, so I would like to think that the hope that the world has, is in recognizing that if there’s anybody with that hope, then there’s no hope for anyone.

So in a sense, if that woman in a Bundelkhand village where we work isn’t going to have a better life then it’s going to have an impact on us too. Partly through population growth, partly through destruction of forests and soils and and rivers, partly through breakdown in the economy. And also it is not inconceivable, though India may be an exception, for societies to break down.

And, you know, destroy everything that we’ve been able to, to create so far in civilization. I think there’s, I don’t think that we need to go into a dead end. We need really now to think of changing the relationships between people and nature, people and people, so that we have how would you say justifiable?

PAT

I think it’s a question of waking up every morning and, you know, remembering that if there’s one person without hope, then there isn’t much hope for all of us. Or, you know, Robert Kennedy, you remind us often of, you know, what he said.

ASHOK

Well, you know, that’s about creative, creative solutions.

You know, he a few minutes before he was assassinated, he was making a speech and he said, you know, there are people around who look around them and ask, you know, why, why you think so bad? I look around me and ask why not? Why can’t we solve them? So in a sense, that’s what he is about. We’re in the business of solving those problems which automatically means you’ve got hope otherwise why would you be wasting time?

PAT

Thank you so much, Doctor Kosla, as always. Every conversation with you is not just a pleasure, but it’s a huge learning experience. I’d like to thank you for, you know, the privilege of having, you know, worked with you for more than 35 years now. So thank you very very much.

ASHOK

Thank you, Pat. It’s been a privilege to work with you and with all your colleagues. It’s been rewarding. I must admit. Roger Ravelle, my partner in crime with climate change used to say, he was already about 80 years old, used to say that he never had an academic year when he didn’t teach a freshman class because it was the only way to keep alive. So this is nice for me. That’s where I have is young people thinking and you get new ideas every day.

OUTRO

HOST

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.