E12

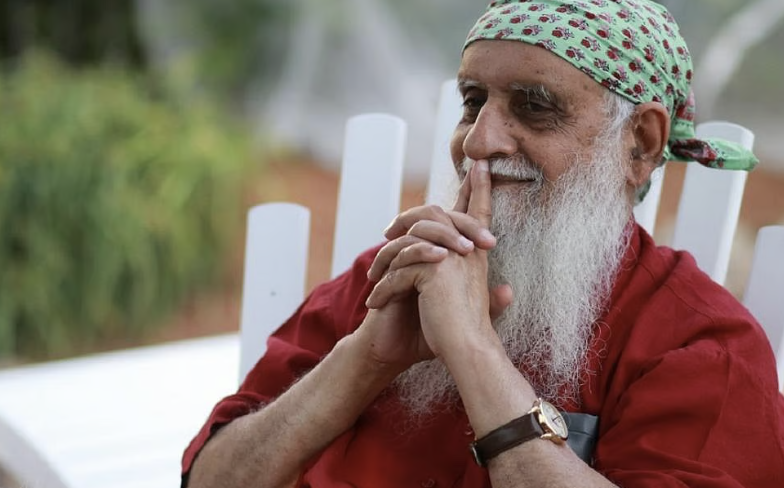

Dr Ravi Chopra says that selfless service is an article of faith

In this episode of Grassroots Nation we hear from Dr Ravi Chopra is the founder Director of the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun, Uttarakhand. Through his career he has helped establish several pioneering organisations in the social and development sector, from livelihoods, disability rights, human rights, water resources management and much more.

Dr Chopra is in conversation with Suchitra Shenoy, a non-fiction writer who has worked extensively in the social sector.

This conversation was recorded at the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Dr Ravi Chopra

Born in 1947, the year India gained her independence Dr. Chopra was one of the country’s midnight children. After earning a B.Tech. in Metallurgical Engineering and Materials Science from IIT Bombay in 1968 he went on to complete his doctorate in Metallurgical and Materials Engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology, New Jersey.

Dr Ravi Chopra has always been guided by his keen interest in the interactions between technology, society and the environment and his unwavering belief in the role of young people in nation building. He has spent his entire career of over fifty years committed to improving the lives of his fellow Indians and has been associated with many different organisations and projects, from FREA,to helping produce the first citizens’ report on The State of India’s Environment in 1982 to working with pani panchayats, PRADAN, and finally establishing the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun in 1988. PSI as it is commonly known has pioneered work in water resources management, environmental quality monitoring, disaster mitigation and conservation of rivers, particularly in the Himalayan region.

From the optimism of the 50s to the tumultuous years of the Indo-China War and the Emergency, to more recent upheavals in the nation, Dr. Chopra recounts the story of both his life and that of this nation. Both are deeply intertwined.

Dr Chopra lives in Dehradun with his family. His wife, Jo Chopra Mcgowan, is the founder of the Latika Roy Foundation.

Suchitra Shenoy

Suchitra Shenoy is a writer & author, who co-founded the Inclusive Markets team at the Monitor Group, that examines market-based solutions to poverty.

We had a lot of role models which gave us that faith that you can leap into the dark, and society and people will take care of you..now those values are disappearing or maybe in some parts may even have disappeared. So we should not really think in terms of replicating that. But one thing I will keep saying to people, especially the younger people, that if you do good work it is selfless. The keyword is selfless service. You, your work will be recognised and people will take care of you. That is an article of faith now, there's no doubt about it.

Dr Ravi Chopra

TRANSCRIPT:

HOST

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

Dr Ravi Chopra is the founder Director of the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun, Uttarakhand and through his career he has helped establish several pioneering organisations in the social and development sector, from livelihoods, disability rights, human rights, water resources management and much more.

Dr Chopra was born in 1947, the year India gained her independence and grew up in Bombay. He earned a B.Tech. in Metallurgical Engineering and Materials Science from IIT Bombay in 1968 and went on to complete his doctorate in Metallurgical and Materials Engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology, New Jersey.

Dr Ravi Chopra was always interested in the interactions between technology and society and the environment and he returned to India with a desire to contribute to India in some way, and he has spent his entire career of over fifty years committed to improving the lives of his fellow Indians. He has been associated with many different organisations and projects, from FREA,to helping produce the first citizens’ report on the The State of India’s Environment in 1982 to working with pani panchayats, PRADAN, and finally establishing the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun in 1988. PSI as it is commonly known has pioneered work in water resources management, environmental quality monitoring, disaster mitigation and conservation of rivers, particularly in the Himalayan region.

Dr. Chopra has served on various committees of the Indian Government, including committees of the Ministries of Rural Development and Water Resources, Government of India, and the Planning Commission, he has been a member of the National Ganga River Basin Authority, chaired by the Prime Minister of India.

Dr Chopra lives in Dehradun with his family. His wife, Jo Chopra Mcgowan, is the founder of the Latika Roy Foundation.

Dr Ravi Chopra is in conversation with Suchitra Shenoy, a non-fiction writer who has worked extensively in the social sector. Suchitra is a founding member of the Inclusive Markets team at the Monitor Group, that examines market-based solutions to poverty.

This conversation was recorded at the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun.

SUCHITRA SHENOY

I’m thrilled to be here with Doctor Ravi Chopra, who is for many people a huge inspiration. All of us in the social sector have grown up hearing all these names, and

Dr. Ravi Chopra certainly is one of them. He’s also a dear friend. And so it’s been wonderful to listen to the stories and to be given this opportunity to be here for this conversation. So Ravi, to start off with an interesting question, how many newspapers do you read every day and in how many languages?

RAVI

Thank you Suchitra. Currently I read seven newspapers every day. I scan them first thing in the morning before breakfast and they’re in two languages – Hindi and English, local and national. And then on the net I read the New York Times.

SUCHITRA

And you used to have a higher number, it was thirteen or something, right?

RAVI

Well, it fell from thirteen, to nine, and now seven.

SUCHITRA

Even in the newspaper reading from what I remember, you would actually subscribe across the spectrum, right? In terms of right wing, left wing, just to get a sense of that political environment.

RAVI

Yes, not only political, but also the kind of news, for example, I subscribe to a local newspaper which focuses almost exclusively on Dehradun city and Uttarakhand. Then I used to get Tribune until last year, which was focused on Himachal Pradesh. Times of India and Economic Times are the establishment newspapers, as is Amarujala. Hindustan, Indian Express and The Hindu are slightly to the left of centre and not always reporting the establishment viewpoint.

SUCHITRA

If we move now, continuing with the political and economic, but to move to the 50s and the 60s, can you share with us the kind of critical influences of your younger days? What was the political and economic climate like in those decades?

RAVI

First of all, I often like to tell people that I’m one of India’s ‘Midnight Children’, born in 1947, growing up in the 1950s, when there was a tremendous air of excitement. There was a mood of nation building, we’ve just become free and we can make this country the way we want it to be, so the atmosphere was full of hope.

MUSIC

My exposure to the political world began with our own family. My mother’s uncle was a staunch Congressman who had been picked as a Jeevan Dani for the freedom struggle by Lajpat Rai. And he’s a very simple person who had, I think 3 or 4 pairs of kurta pyjamas, when he travelled he had a mini holdall, you know, to keep all his stuff. He carried it himself, he had all the privileges of a Parliament member but would hop on to the local bus to go to the train station. And an extremely simple person but tremendous amount of respect for him in the family. So that was my first role model – this man who’s so simple, he’s getting so much respect.

And then Nehru was of course the commanding leader of the country at that time, and people really love Chacha Nehru. I mean, the very fact, he was called Chacha Nehru, sabka chacha hai woh. And I remember him coming to inaugurate the first Bal Bhavan in the country, which is right within walking distance of our house, and all of us crowded into the lawns of Bal Bhavan waiting for Chacha Nehru to arrive. So it created a great deal of excitement at that time. That excitement lasted throughout the 50s I would say and it’s only when the Indochina War took place in ‘62 that things began to turn over.

SUCHITRA

So the energy and the hope and the sense of building a nation altogether and also service to the nation, right? So one of the things that struck me was how these seeds of service, I mean, you studied at IIT Bombay, one of the best engineering schools of India and these days when we hear of the IITs and the IIMs, it’s fine and understandable, but you also hear very often just about the big pay packages that the alumni get, the graduating class gets. But I remember you saying in your class there was very much a sense of, we should be job creators, you and your friends thought, not actually going out and seeking jobs. How did that come about?

RAVI

Well, that ties in with the era, with the decade of gloom and doom that came in the 1960s. So the war against China came as a big shock to the whole country, and the fact that we were so unprepared and were totally vanquished in the field was even more depressing for the nation. The good thing was that the nation rallied behind the armed forces, but I guess Nehru himself received a big shock, and shortly after that he suffered a stroke and then passed away. Now at that time there used to be this big discussion in the country – what after Nehru? Not who after Nehru, what after Nehru? Because many commentators, particularly outside the country, felt that it was Nehru who was holding the country together, and once he was gone, then there would be chaos. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. That little short five feet tall Prime Minister Shastri showed that he was no less a leader. But then soon after he became the Prime Minister, I would imagine in less than a year’s time, there was the Indo Pakistan War.

And that’s where Shastri came into his own when he, you know, gave the slogan ‘Jai Jawan Jai Kisaan’ and he exhorted the country that look, we are passing through a very difficult time. It was not a short war, by the way, you know, it was not ten days, fifteen days, it was I think something like four months long and then the UN imposed the ceasefire. So he said, “We are going through a very difficult time and we should, wherever possible, families that are well off should at least try to miss one meal a week so that other people can have food to eat.” And that idea caught on, especially amongst us. By then I was at the end of my first year at IIT, and so many of the students responded very positively. And when he said, “Jahaan bhi ho, jo bhi ho, agar aap kuch khane ka samaan uga sakte ho, to ugaiye.” So I remember at home on the third floor of the building, getting these little plastic boxes and stuffing them with dirt and trying to plant tomatoes. At the institute we uprooted the hostel ground, at IIT we uprooted the hostel ground and we decided to plant vegetables. Now we were all city…

SUCHITRA

Right, boys.

RAVI

… boys. We had no idea what farming or growing culture is. So of all the things as we are plucking out the grass of the lawn, we find all these earthworms, so we started throwing the earthworms out. But at the national level the mood really turned sombre. 65-66-67 period of tremendous droughts in succession and we were said to be living ship to mouth – PL 480 ships coming.

MUSIC

It was a gift from the US. Unloaded, then the grain would show up at the ration shops and then people would get that grain to eat. At that time two American brothers George and Bill Paddock, came out with a book called Triage. Triage is the theory that you know if a ship is sinking, you first save the able-bodied so they can help the others. So these two gentlemen suggested not to give food aid to India. Their argument was that India is a basket case, it’s got too many people. And one of their sentences was something to this effect that by the mid 70s, people will be dropping dead on the streets of Indian cities because of hunger and malnutrition.

AUDIO- NIXON TAPES (“My God, South Asia is just unbelievable,” he once said. “You go down there and you see it in the poverty, the hopelessness…”)

Now this came as a shock to us. I mean here Pandit Nehru had been telling us all in the 50s that we are going in for planned economic development, by the end of the second or the third five-year plan will be a strong and healthy nation, logon ke chehere par khushali hogi aur kheton me hariyali hogi. And the country was sliding into poverty, abysmal poverty. So some of us got together and we said, “Who’s going to get India out of this mess? It’s up to us. We should come forward and do something for the country.” And that’s when we said that instead of looking for jobs ourselves, there were no jobs available, unemployment was rampant and that’s why you had the… We are thinking this way in the west, and in the east, in Bengal, the Naxal movement is gearing up. So that was the mood of the country which made us think about our role in nation building.

SUCHITRA

And you are part of a whole generation, right, of these nation builders? Dunu Roy calls you his langotiya-yaar or chaddi-buddy, as some people would say. There’s a whole generation of you all. There’s Anil Agarwal, Aruna Roy, Ela Bhat, I mean, all of these are people who’ve established national organisations. Tell us a little bit about this kind of intergenerational camaraderie and the spirit of building an independent India.

RAVI

So in the 50s and I would say up to the mid 60s, the non-governmental organisations were either some variation of charity. So focusing more on doling aid or on at best building schools and colleges. There were political parties, there were trade unions, but you did not have any developmental organisations as such. Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation came into the picture, but they were operating at the government level also. It’s after the droughts in the 60s that people of my generation, the Midnight’s Children started to get active. Bunker went to Bihar to work with AFPRO and then when the work was done in Bihar, would be around the late 60s, then he borrowed three rigs from AFPRO and said I can use them to look for water in Rajasthan, which is a very dry state and also extremely poor, so Bunker took off from there.

SUCHITRA

And can you just tell us what he set up?

RAVI

Yes. He set up the Social Work and Research Centre in Tilonia, Ajmer district. So Bunker went off over there. We started a group at IIT around 1967 and offered our services to other organisations that could use some engineering talent or skills. Didn’t get very far and shortly after that I encountered a gentleman named Professor PK Mehta, who was visiting India from California. He told me about an organisation called FREA, Front For Rapid Economic Advancement of India, and he said that this had been set up also to, amongst people who are extremely conscious about being Indians outside doing well and how can we contribute to India’s development. So they had set up FREA and then realised around 1967 that we are sitting in the US, how can you have rapid economic advancement in India by sitting in the US? So a number of them came here, came to India, but very soon they took up jobs and then their first priority was their job, so where is the time to do rapid economic advancement? So when Professor Mehta met me in the summer of 1967, I told him about this little group that we had at IIT Bombay. And I said, “I’ll talk to my friends and if they are agreeable, why don’t we become the first chapter of FREA in India?” And that’s how FREA started in India. And in ‘68, shortly after I graduated like everybody else from my class, I too joined the hoards going abroad. But before going abroad, I went to Dunu, who was one year my senior, and I said to him, “Dunu, we’ve set up this thing called FREA and how about if you take it over, why don’t you run FREA?” Dunu was really one of the most well-rounded students ever to graduate from IIT.

SUCHITRA

This is Dunu Roy?

RAVI

Dunu Roy. And he was very good at studies, he was a good sportsman, he was very good at Fine Arts, he was a good writer and absolutely everybody admired him and you shouldn’t be surprised that the gold medal for the ‘Silver Jubilee Best Student’ produced by IIT went to Dunu Roy, and the ‘Golden Jubilee Best Student’ produced by IIT went to Dunu Roy. So I went to Dunu and I said, “Can you take over FREA?” He was doing his masters then and he said, “Get lost! Let me finish my masters, you guys manage FREA for a while and that’s your problem. I’ll join after I’m done with my masters.” And really, it’s amazing, he came over as soon as he finished his masters, he took over the leadership of FREA. I tease him now saying that, “If you had accepted that job at Hindustan Unilever, you would have been the chairman of Hindustan Unilever, dekh tereko kahaan phasaya maine.”

SUCHITRA

Can you give us an example of a project that FREA did in the late 60s?

RAVI

Well, I don’t know how much time you have, but there is this… You start with a failure, right? So in 67, when we were still discussing how to be useful, a gentleman named Thomas Abraham came to meet us and he represented an organisation called India Village Advance. He was working outside of Pune and he said, “Look, I’m working in a very poor village, I have a campus, why don’t you guys come to Pune in the summer and you work with our team over there.” So we said, “Fine,” and come summer time, we decided that eight or ten of us were willing to go to Pune. We show up at his campus and the gate is locked. Finally we found somebody, who said, “Doctor Saab toh bahar gaye hue hai.”

So we said we’ll wait till he comes back, he said, “Voh bahar gaye hai, abhi nahi ayenge, ek do din ke baad ayenge.”. We told him our story and he gave us some place to stay. We waited, Doctor Abraham didn’t show up, so we thought, now what do we do? We can’t just go back to Bombay and tell our friends ye kuch nahi kiya. Kuch toh karna hai.

So we talked to the villagers and the only thing that we had tried to equip ourselves with, on, “What will we do when we get there,” was sanitation. So we had a simple idea of what used to be Gandhiji’s favourite idea, of his latrine. So we told the villagers that, “We can put up latrines over here, very simple latrines, would you be interested?” So immediately the Sarpanch’s hand goes up, so we are happy. Immediately the Up-Sarpanch’s hand goes up, so we were thrilled. So we said, “Okay take us to the location where you want the latrines.” And it took us to the end of the village. So we put up these very simple latrines with a textile partition, and after they were ready we went back to IIT, we told our friends of what great work we had done and they said, “Yeah, but what’s happening with those latrines? How do you know they’re being used?” So we sent some of our friends back to the village, “Jaake dekh ke ao, kya ho raha hai.” They came back and they said, “Nobody’s using those latrines, they have goats sitting around and shitting all over the place!” So that was our first lesson on how not to do development.

MUSIC

But Dunu when he took over, he first acquainted himself with what was going on in the country. So he went and he met some organisations, a lot of Gandhian organisations, and he decided that there were people like us, at IIT from urban areas, who had no idea of what is poverty, why people are poor, and how on earth will you get rid of poverty. So Dunu thought that the good experiment would be to begin with a Student Volunteer Programme. So he started this programme where every year he would spend several months visiting colleges, professional colleges, medical colleges, engineering colleges, probably a few law schools, and talking to the students there, telling them about what they could learn by working for a while with poor communities. And that was a great exposure for a lot of students. I remember by ‘73 or ‘74, JP movement had started in Bihar and there was the Everyman’s Weekly and JP used to write an article for every issue and he talks about these three organisations in the country that were really setting a good example for the youth of the country and it was a call to action. So FREA was one of them. And by then Dunu had been taking about over 300 people to work in the summer and after their summer exposure, then there would be a workshop where students would narrate their experiences, what they learned and what they did. And basically he would organise work for them, which if they did it, and did it well, it was a great benefit for the community. If they messed it up, nobody suffered. So there were things like, doing all kinds of surveys for the community. And it created a whole generation of activists. So you are from Hyderabad, right?

SUCHITRA

Yes.

RAVI

You must have heard of a person named Sagar Dhara, right? Sagar Dhara is from FREA. Javed Anand, Communalism Combat, he’s from FREA. So there were a whole generation of people who came out of FREA, and did some wonderful work.

SUCHITRA

So you’ve brought us to the 70s and JP. Can you talk us through your experience of the 70s? I mean, the Emergency has kind of faded from current day Indian memory. So could you describe to us, you were in the US, you were studying the shock, the effects it had on you and your generation, and then the 1984 riots and what you did, what your role was in those crises?

RAVI

Professor Mehta had come to India for a sabbatical in 73-74. When he returned back to the US sometime in September of ‘74, shortly after that, we held a workshop of people who were interested in India’s development. So there were something like 60 or 70 people from all over USA who showed up. At that meeting Professor Mehta talked about the turmoil that had taken place in Gujarat, the student movement against Chimanbhai Mehta and his corruption, Navnirman movement, and he said that it had now spread to Bihar also and the country was in a big turmoil at that time.

HOST

The Navnirman Andolan or the reconstruction or reinvention movement was a socio-political movement in 1974 in Gujarat by students and middle-class people against economic crisis and corruption in public life.

RAVI

There was a lot of corruption, people were unhappy, people were not still not getting jobs etc. And there had been big droughts in 71-72 in Maharashtra and Gujarat and there was a drought in Bihar. So he said that he was quite apprehensive about whether India would be able to overcome these difficulties.

In January we then decided to set up the India Development Society, which would bring together most of these disparate groups in the US. So that initiative began, and one day I received a call from a friend in the Midwest who said, “Hey, there’s this young new student at the University of Chicago, a fellow named Anand Kumar. He was a part of the JP movement, why don’t you try and get in touch with him?” So I arranged for Anand to come and visit me in New Jersey and I also arranged with a professor at Columbia University, Dr. BN Verma who was from Bihar. And we had a meeting at Dr. Verma’s house. Anand talked about the Bihar movement, the JP movement and the role of students etc. And we said that, “Look, there, people in the US are simply not aware of all this. Can we send you on a speaking tour in summer?” So he said, “Sure, why not?” So the India Development Group arranged a speaking tour at all the different locations where our friends were, which started in early June.

Now sometime in June, a friend of mine, Srikumar Poddar shows up at my home in New Jersey and he says, “Can we have a meeting with the students at your university?” And I said, “Sure why not?” So we had a meeting and at that meeting he said to the students, he said, “You know, if all the laws are subverted in India and the government declares a state of Emergency and you have no human rights left, what will you do?” Immediate howls of protests. “Can’t happen in India,” “don’t talk nonsense.” So nobody believed that. And a few days later, 25th June, late night, the Emergency is declared and Anand Kumar lands up in, that was his date for a talk at Columbia University. That talk was going to be on the 26th. News had already appeared because India is ahead time wise.

MUSIC

So I get a call from Columbia University early in the morning saying maybe we should cancel Anand Kumar’s talk today. I said, “Look, the guy has come all the way from Chicago and he’s come just for this function. We can’t cancel it, what’s your problem?” So they said, they’re getting feelers from the embassy, from the consulate, “ki vo jo apka programme hai, cancel kar dijiye.” I said, “No, don’t do that. What you tell them is that we will have Anand Kumar talk as planned and a representative of the government can also put the government point of view, so let the people hear both points of view.” So it was agreed and that was quite a performance. So 26th, Anand, myself talked through the night. We talked to our friends in other locations. 30th June we showed up in Washington to protest outside the Indian Embassy.

At that time we also decided… about 25-30 people. That’s all. Bohot zyada nahi the. And we decided to set up an organisation called Indians for Democracy. So I went back and all of us went back to our locations, I went back to New Jersey. I lived in New Jersey, across the River Hudson from Manhattan. So I started contacting people in that New Jersey, New York area, and very soon we had a chapter of Indians for Democracy. They were very clear that we want nonviolent protest and if you are non-violent and you are fighting for civil liberties, we are with you. So we began and the next date was of course 15th August and we organised, tried to organise a bigger protest. About 60-70 people showed up.

So that day we decided that we should have some kind of a newsletter to inform Indians of what was going on in the country. I took over the editorship of this newsletter and I called it ‘Indian Opinion’ following Gandhiji’s newspaper in South Africa. So that was a major role that I performed while I was there. And of course, trying to expand the Indians for democracy, getting more people involved.

Then in August or so July, August of 76, there was this talk of new legislation to curb the Fundamental Rights– 42nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution. And Professor Mehta then says, “Look, if they pass the 42nd amendment, I don’t want to be an Indian citizen. I will do a padyatra from Boston to New York, and at the UN I will burn my passport.”

MUSIC

I’m sitting there. He’s supposed to be my mentor. What is he going to do, walk all by himself? So I said, “If you’re going to walk, I will work with you. Then Anand Kumar said, “I’ll walk with you,” and pretty soon there were a few of us. So I organised that walk and as you probably know that at that time the nonviolent movement in America was also very strong. They had coalesced with the civil rights movement and the disarmament people had come together. So they were doing this huge, massive walk from San Francisco to Washington – the walk for Disarmament and Social Justice. And they had feeder routes, joining them North-South directions. One of them was coming from Boston to Washington.

The people who are organising that walk was a group called War Resisters League which was an international organisation. JP had been one of the founders in the 40s and I had gotten to know them because of the anti-Emergency effort. So I went to them and I said, “How do you organise a walk?” So they helped me organise a walk. They said, “Don’t do this Boston to Washington, it’s too long for you guys, you don’t have enough people. Instead do a shorter walk.” So we came up with Liberty Bell in Philadelphia to the United Nations in New York, about 100 miles.

We did that walk and as you probably know, that’s where I ran into Jo, or Jo ran into me, on the highway because she was walking from North to South and so…

SUCHITRA

That’s the lovely personal romantic bit.

RAVI

Which still survives.

SUCHITRA

So shall we move from those days a little bit, a decade maybe, ahead to the 1980s? You’d move back to India, Jo and you were married, and the riots in Delhi and the crisis after that.

RAVI

Yeah, Jo and I came here at the end of February 1981. And then when our first child was to be born, Jo wanted to go back home. And there’s a nice Punjabi custom that the first child is delivered at the maike. So I said, “Okay, we’ll go to the US.” So she went there, and she also studied to be a midwife while she was there, and I joined her at some point. We came back in 1984 October and I had gone back to work at CSC because CSC was engaged in bringing out the second Citizens report.

SUCHITRA

And CSE was?

RAVI

Centre for Science and Environment established by Anil Agarwal, my dear friend. I had just gone to Delhi and I told Jo and I said, “You stay on in Bombay with my parents and I’ll go and look for a flat and then I’ll take you to Delhi.” But 31st October, Mrs. Gandhi was shot and killed.

MUSIC

And then the riots broke out and we were shocked. I remember I was staying at the home of an uncle Krishnakanth in the Connaught Place area. The next morning as I was going to… I was staying with Anil Agarwal and Press Enclaves, Southern Delhi. So as I went to Press Enclaves on the way I saw that there were some buses were burnt and there was some smoke coming from some places. So I was very surprised what happened. When they reached there, a friend of mine, Poonam Muttreja, called me and said, “Listen, do you know about the riots?” And I said, “No, what riots?” She said, “We are meeting at the home of Sumanto.” Sumanto Banerjee was another journalist and she said, “Why don’t you also come?” He lived in Press Enclave. I said, “Sure I’ll come.” So that morning, about 10 or 12 of us gathered at Sumanto’s home. And different parts of Delhi, there are reports of riots and Sikh communities being attacked and people being killed, so we should do something, but do what?

So we first decided let’s go around the town and see what was happening and somebody said, “Par woh curfew laga hua hai, kaise jayenge?” So very quickly we made a sign ‘Press’, put it in front of Poonam’s jeep and we started travelling around. We went and first got hold of Swami Agnivesh.

Swami Agnivesh was an Arya Samaj Swami who was known for his left of centre views and had started this thing called Bandhua Mazdoor Mukti Morcha to get people out of bondage. And I had gotten to know him because I had written some pieces on the labour camps for the building, the stadia for the Asian Games in 1982. So we picked him up and we decided we would just go around the town. And having him with us, known face, the police was less likely to bother us. We ran into some friends of Rajiv Gandhi and we said, “Do you know what’s happening in the country?” And so that was the first time we heard that line, “You know, when a giant tree falls in a forest, everybody hears.”

So we were quite disappointed with that response. By the time we came to Lajpat Nagar, we saw that there was this, this is the Lajpat Nagar Market in Delhi, and we saw that there were some young kids who were setting some shops on fire. So immediately Swami Agnivesh got out of the jeep and as soon as he got out of the jeep, “Idhar ao, idhar ao!”

All the kids got scared and ran away. So he got up on a makeshift podium and delivered a speech, “You’re not burning anybody shop, you are burning the nation. Please be careful what you are doing. These things will have long term repercussions. The Sikhs are no less than us, they are our brothers.” And soon, pretty soon a crowd collects and then somebody invites us home, “Achcha chai toh peelijiye.” So we went, we talked to about 30-40 people who collect in that drawing room, and we had a discussion. I said, “Par Swamiji, aapne suna? Aaj toh Amritsar se gadiyan aayi hai laashon se bhari hui!” Swami Agnivesh said, “Aapne dekhi?” “Nahi dekhi.” “Aapne dekhi?” “Nahi dekhi.” Nobody in the room had seen it, it was a rumour. So, he said, “Why do you believe rumours?”

By then we had made phone calls to other people and we had organised a small meeting of activists in Lajpat Bhavan. So 4:30 in the evening we are sitting there, we have this meeting, and it’s decided that we would set up some kind of a relief effort to intervene. As the meeting is progressing, somebody comes out, “Arre, they are burning a gurdwara over there!” So meeting cancels, we take out a march to that gurdwara. By that time, the gurdwara is already on fire, it’s burning, and people are rushing around with buckets of water to throw the fire out.

AUDIO- fire

No response has come in from the fire department. And then we hear that there’s another kind of fire that’s breaking out in another part of Lajpat Nagar market. So we take out this march, shouting slogans of “Hindu Sikh bhai bhai,” and all that. And we went back to Lajpat Bhavan, decided that at night we’d go and meet the opposition leaders and next day we will take out a big march through Lajpat Nagar because that was a hotspot. And I lived nearby in Lajpat Nagar. I went to see Chandrashekhar whom I had known earlier. And he said, “Main abhi jaa raha hoon, Pradhan Mantri ne meeting bulaya hai, kal subah National Executive Janta Party ki National Executive ka baithak hai. Aap subah aake bataiye kya haalath hai sheher mein. Aur agar aisi hi haalath rahi, toh hum aapki march mein poori National Executive ko le ayenge.”

So the next day things were as bad and we had done an early morning recce. By 5 o’clock in the morning we had gone around various parts of the city. So 9 o’ clock I went to the party office and I said, “Things are as bad.” In the meantime they’d received news that Madhu Dandavate was supposed to come for the meeting. His train has been stalled somewhere and people are beating on the windows of the train to see if there are any Sikh passengers in there.

We did the march and all the Janata Party came and there was one very, very unusual moment. So we are walking through a narrow lane and suddenly from the other side a group of young men come shouting slogans with talwars in their hands. We are walking about three or four in our line and the guy next to me, he says, “Kya karna hai?” “Kuch nahi, khade ho jao,” and I held both the hands very tight, should anyone try to run away. I mean, I had not the foggiest idea of what we were going to do, but I figured Chandrashekar is somewhere at the back. He’s tall, he should be seen, they might stop. And then my friend Poonam, who was in the next row behind me, she said, “Ravi, you come back.” And she and her friends, they moved to the front. So they moved to the front. I thought that was a brilliant idea because she was a woman, they were not going to harm a woman. And we are about this distance where you and I are sitting now about what is it about a metre and a half? And suddenly there is a flag march, a contingent of army people coming through with a white flag. And the youth saw them and then they immediately ran away.But that was a very decisive moment for me that you know, when this guy said, “Kya karna hai?” I said, “Kuch nahi khade ho jao bas.”

So at the end of the walk, we set up the Nagrik Ekta Manch. The next day we moved into the Lajpat Bhavan grounds and we organised a relief effort which took care of about 50,000 people in Delhi who had been rendered homeless for over a month or so. During that period we also mobilised a lot of support for their rehabilitation. The houses had been burnt, shops had been broken into, people had lost their livelihoods. So to restore all that, we got tremendous support from the people of Delhi, even the big business houses – HP Nanda of Escorts came forward. The Charatram Bharatram families came forward to help and lots of organisations came forward. It was a tremendous effort. We had opened maybe about 15 or 20 relief camps throughout the city. Every evening we would get a report from each one of the camps. Somebody would come at about 4 o’ clock and would give us an oral report. Anil Agarwal, I convinced him to step out of CSE and he said, “You put out a press release, we’ll hold a press conference every day.” 6 o’ clock in the evening there would be a press conference, Anil’s press release would be issued. It was quite an effort at letting people know what was happening. And the next day, 9 o’ clock would be an early morning meeting of the volunteers ki aaj kya kya karna hai. After the press conference in the evening, we would get a list of requirements from the teams. Alok Mukhopadhyay, who was then with Oxfam. I was staying at his house during those days and he and I would sit awake till midnight figuring out how we are going to mobilise all this stuff by tomorrow. And in the morning the press would come, “Can we go and visit some of your camps?” So as our volunteers would be leaving with all their packages, they would go. They would then report Eyewitness News and so on. So it led to a tremendous amount of support from the people of Delhi. And Nagrik Ekta Manch, I think survived for about a year or so.

MUSIC

SUCHITRA

When you talk about that decisive moment of marching in this tiny lane and being faced by these young, angry men with swords, it really kind of putting into action all that one might believe in nonviolence, right? You might think about it and believe in it and talk about it, but it’s really at that moment when you’re tested. So can we shift a little and talk about growing up in Bombay? It was still Bombay in those days. Your parents moved from Pakistan. What was growing up like? And what are some of the habits that you can see that have really stood you in good stead over the years and that you still carry with you now, decades later?

RAVI

You know we lived on what was then called Queens Road, now Karve Marg, right opposite the Charni Rd Station, local trains. And the first train would come at 4:40 in the morning. And when it came, I would wake up. I was an early sleeper, I would be asleep by 9 o’ clock at night, so I’d wake up at 4:40. And I couldn’t do anything. Small house, there are lots of people sleeping around, you can’t do much. So I got into the habit of doing my homework in the morning so as not to disturb anybody, and that habit stayed even. Now I get up very early in the morning and before the newspapers come to distract me, I have done some work.

The second thing was that there was a certain amount of discipline that got instilled in us. We were supposed to complete our homework before going to school the next day. That was sine qua non. At home my mother had this system that every week we were four kids and we had lots of cousins who would be staying with us for different periods of time. So every week she would assign a duty to each one of us. For example, one week I might be asked to iron all the clothes, right? So that was my job. Another week, my job might be to pick up, pick up all the beds and stash them at one place or another week, lay out the beds at night, etc.

And I recall this so vividly – one day I was cleaning the carpet. There was a small wouldn’t handle brush and that was used to brush the carpet and I was doing that and my father just casually says to my mother, he said… I’ll say it in Hindi now though he said it in Punjabi, “Yeh iski badi achchi adat hai. Isko koi kaam dedo na? Toh ye khatam karta hai. Jab tak khatam nahi ho jaye, tab tak hilta nahi hai.” I overheard that remark and I said to myself, “This is something that they appreciate. And just that chance remark has stayed with me all my life, that if I took on a job, I made sure that I finished it.

MUSIC

And the hardest part was finishing my PhD. By then my attention had wandered everywhere possible, the Emergency had come along, then I wanted to set up this programme on appropriate technologies at the university. To me, the PhD was the last concern. But then a time came when the school authorities issued a warning to me that you are reaching the end of the period for a PhD and I then decided to buckle down and do my PhD. And I did finish it. It was a good, good thesis. Everybody appreciated it. So even, you know, like we’ve faced a lot of difficulties after that. But that’s the thing that has stuck with me and on that basis I’ve learned that what remarks parents make in the presence of children are extremely important. And it’s good to encourage children from time to time when they are doing some good work. Another ethic in our family was, you are expected to do well. So if you did well, you didn’t get a pat on your back. That was what was expected of you. You had to do something more. So that was a bad habit that I picked up, which was that if people did what they were expected to do, I didn’t pat them on their back, I didn’t encourage them, I used to think, “Isko karna hi tha.” Growing up at home, these were some of the values I got.

Then, of course, there was that role model, my mother’s uncle. And you have to live a simple life. You have to share what you have. So you live within your means but if there are other people who need something, then you have to share whatever you have got. So these were those values. And growing up in Bombay in the 50s was a delight. I can’t imagine a better place to grow up in. It was a lovely city, not overcrowded. I don’t know how old you people are, but when I went to Bangalore in the early 80s, it reminded me of Bombay in the 50s.

AUDIO – peaceful cityscape

Beautiful, it was a green place, nice footpaths for us to walk on, not too much traffic. And in our school we saw no discrimination of any kind. There were Muslim students, there were Christian students, there were Parsis, there were Jains, and there was of course lots of Hindus and so on. And while we ribbed each other no end, you know, we would have Punjabi jokes, we would have Sikh jokes, we would have Marwadi jokes, Sindhi jokes, making fun of everybody, nobody took offence. Because you could always make fun of the next guy. So there was none of that.

And Xaviers High School was a very interesting place where you had children of millionaires coming and children coming from very poor families also. So because we all had to wear the same uniform, the only way you could distinguish who’s rich, who’s poor, was, “Theesre din pehenke aa raha hai wahi kapda,” or somebody wears well ironed clothes every every day or somebody is coming in a private car or car comes to drop him. Otherwise, once inside the school there was very little to distinguish each other. So I think that was a great upbringing, and as a result of which, I can even now, even though I have been away from Bombay for a long time, I’m very comfortable in Gujarati and after couple of days of being in Bombay or Maharashtra, I am quite comfortable in Marathi also.

SUCHITRA

The multilingual Indian?

RAVI

Yes

MUSIC – THEME BREAK

HOST

In this next section Ravi Chopra and Suchitra speak about the main mentors and influences in Dr Chopra’s life.

SUCHITRA

Building on childhood onwards, one important role I think for a lot of people is the role of mentors. Could you talk to us about mentor figures in your life, other friends who you might have learnt from? You’ve mentioned Dr. Professor Mehta, you’ve mentioned your dear friend Anand Kumar… Just a little bit about what you learned from them and others.

RAVI

First, I’d like to just mention that before the mentors, there were some very important people who were responsible for critical turning points in my life. I’ve talked about Achint Ram, my mother’s uncle. This most important person, again, I can pinpoint the moment, is back in 61, early 61, a friend of mine comes rushing home one evening and he says, “Ravi chalo chalo woh Chowpatty pe Rajmohan Gandhi aaj ek bhashan de raha hai.” And I got a chance to sit on the dias, “Ek aur seat ban jayengi, tum bhi chalo saath mein,” so I went with him. And Rajmohan at Chowpatty beach, he gave a very stirring speech. He was a young man himself, must have not been more than in his late 20s or something. Gave a stirring speech and saying, “We have to build this nation, nobody is going to come from outside to build it. And it’s the young people who have to build this nation.” I was really turned on, so I went home and I told my parents, I said, “I don’t want to study, I’m going to get into nation building.”

SUCHITRA

Rajmohn Gandhi has said so.

RAVI

Rajmohan Gandhi has said. Got a slap in response, “At this age, you are supposed to study. You finish your studies, then you can do what you like.” Of course, they never kept to that promise either. So that was the turning point that set the rest of my life for me. The third one was of course I’ve talked about Lal Bahadur Shastri and his call to the nation. And then Professor Mehta coming and Professor Mehta I could say was probably the first mentor.

We had before meeting him… The group of students at IIT who were interested in doing something useful had gone to different organisations only to be told, “Abhi to tum college mein ho na? Abhi tum padhayi karo jaakar.” He was the first one to encourage us that we were on the right track and ever since then he gave us all the encouragement whether it was I or later Dunu to develop FREA and right until his very end we would meet from time to time and sometime in the late 90s he said, “Look, I want to do something for the Himalayas.” He was originally from Himachal, so he has been a constant mentor.

After I set up PSI, you know, I studied solid-state physics and you know how atoms or ions diffuse in a material. I knew nothing about civil engineering or building dams and doing all this kind of stuff. So when we set up PSI and I was in charge of two units – water and forest. Dunu was in charge of two units, which had to do with labour. And the young people who joined PSI would often come to me for guidance and I would say, “I don’t know anything about this. I have not studied engineering, I’ve done more of science than engineering. I’m sorry but you’ll have to go somewhere else.” Then GD Agarwal, Professor GD Aggarwal who was also one of the Co-founders of FREA. GD Agarwal was our Chairman and he initiated a lot of work at PSI in terms of setting up an Environmental Quality Monitoring Lab. Doctor Chawla, Kamaljeet, not only a friend but also a mentor. Much of the engineering I know today, whether it has to do with earthquake proof housing or it has to do with dams and rivers, came from Dr. Chawla and of course the rivers, later on, I learned a lot more from GD. And Dunu, Dunu played a great role. Not only did he know his science and engineering very well, but he also knew the social structures within which we had to operate. So I would say that those were very critical mentors. And then much later, I had no management background and this business about organisation processes, how do you organise society and how do you do work in a participatory manner? I could do that in the field, but within the organisation I was a dud and that learning came from my association with Pradhan. And that’s why I admire Deep and Vijay.

SUCHITRA

Deep Joshi and Vijay Mahajan?

RAVI

Yeah, because it was a role model for me to look up to. And of course, I must mention Jo. Jo as often as she could, she would say, “Look, your work in your life, you want work to be the centre of your life. It’s not everybody else’s centre. You have to be more gentle, you have to be kinder to your colleagues.”

SUCHITRA

This is Ravi’s wife, Jo McGowan Chopra.

RAVI

Oh I forgot Chandi Prasad Bhatt. Chandi Prasad Bhatt had been one of the leaders of the Chipko movement and we became very close friends first at CSC. And at CSC it was until who taught me how to write for the public. When I first wrote a few pieces at CSC for the citizens report, he said to me, “Your information is excellent, lekin koi padega nahi.” I said, “Kyu?” He said, “You are writing like a scientist. You are building the background and then you are telling the story,” he says “no, people lose interest. In journalism, you begin with the main thing that you want your readers to read and understand before anything else, put it in the first paragraph.” OK, so he was a mentor of sorts. But Bhattji taught me one basic lesson. He says, “We must, as activists, we must respond to the felt needs of the people.” This phrase was Bhattji’s favourite – “felt needs of the people,” and that’s how we did a lot of our work at PSI. We didn’t decide, we did not have an agenda. We people would come to us with a problem and we would try and respond to it.

SUCHITRA

So that leads us very nicely into People’s Science of India, PSI and the work. So what was the thinking when you set it up, describe to us the work that PSI does and did, starting from dams, rivers, all of that?

RAVI

By the time I had decided to return from the US, I started discussing with one of my IIT roommates, “What should we be doing?”

And I said, “It’s fairly straightforward. We have been trained in science and technology and that’s what we have to use for the service of the people.” So it was that simple an idea. How would you use science and technology in the service of people and solve their problems – this is one of the gifts of engineering. Engineers are trained to solve problems. So we said, “Okay we’ll make an institution where anybody can walk in and talk to us about their problems.”

So PSI began with looking at issues of water, and the biggest use of water is irrigation. The first project I said to my colleagues, I said, “Look, before we get into advising people on what to do for irrigation, let us first understand the subject ourselves.” So for one year we did nothing but study the history of irrigation in India going back to about 5000-7000 years ago till the present.

SUCHITRA

Across the country?

RAVI

Across the country, how irrigation developed in different parts or did not develop. And that really made us understand one thing, that the traditional systems of irrigation, many of which still survive, were quite in harmony with the environment around them. They were not destructive of the environment whereas if we look at the post independence era, there is a lot of destruction of the environment in order to provide irrigation water.

AUDIO – sounds of irrigation

We began with that. Then the 1988 drought that broke out was… 87-88 drought, that led us to study droughts. How do people manage to survive when they don’t know where their next meal is coming from?

My colleagues and I went around the country seeing what could be done in response to droughts. All of a sudden in 1991, came the Uttarkashi earthquake. A bunch of people come to our office and they say we need help in building earthquake safe houses. So I said, “Hum toh pani ka kaam karte hai.” He said, “Aap engineer toh hain na? Haan toh phir aap humko batao.”

And given our basic idea that you have to respond to people’s requests, I raised the issue with the Kamarjeet, Dr Chawla and I said, “Kamarjeet, can you help us?” He said, “Sure.” Now he’s a geotechnical engineer, about the best in the country. And he taught us all the principles of earthquake safe construction. ‘93 there was the Latur earthquake and at that time there were no lots of organisations that knew what to do during an earthquake. So we were also very lucky to run into Laurie Baker in Latur and Laurie Baker was happy to see us. He gave us a lot of time and we were thrilled to be in his company and learning about mud buildings from him.

‘97 was the Jabalpur earthquake, ‘99 was the Chamoli earthquake. By the end of the 90s we had not only understood how to build earthquake safe houses, but a lot more. We had developed a timeline of how you respond to disasters of different scales. So if it’s a small localised disaster, there is one timetable, and if it’s a state level disaster, there’s another timetable. How does the government operate? We produced a lot of very simple basic literature. So disaster mitigation and response became a second field of PSI.

And then from just looking at water one day, Dr. GD Agarwal said to me, he said, “Aapne jo lab banane ki koshish ki hai, yeh toh water pollution ki lab hai. Why don’t you make it into an Environmental Quality monitoring lab?” And I said, “But then isn’t the air pollution equipment expensive? And we don’t have anybody dealing with air pollution here.” So he said, “I’ll help you out.” He had helped some of his students from IIT Kanpur to set up a company which made air quality monitors in this country. So he brought in the idea of converting a tiny pollution water quality testing lab into an Environmental Quality monitoring group. So not only did we have the equipment, but we had people who knew how to use the equipment to generate results and how those results are to be used for campaigning against environmental pollution.

So for a long time these three remained. And then gradually irrigation water involvement gave way to expanded into natural resource management.

In late 89, there was a workshop in Ranchi on dams and some dams had been planned in the Chota Nagpur plateau area, one of which was Aranga Dam. Dunu had gone to that conference and when people came to him and said, “There’s this dam going to be built in our area and 38 villages are going to be submerged. Where can we go for help?” And he said, “There’s the People Science Institute in Dehradun, go ask them.”

During the drought, some of my friends were working there, colleagues were working there and one day I got a call saying, “Ravi, we have a young DM and DDC Deputy District Commissioner and they’ve started this very interesting programme to combat the drought. It’s called Pani Panchayat. But they don’t know how to work that programme and they’re making a mess of it, so all the contractors have hijacked the programme. We need you to come here and talk to them.” So I went and I spent a day with my colleagues and I tried to understand. Next morning I went and met the DDC and he said, “You’ve just arrived here, why don’t you go around the and just to go to some of the places where the dams are being built, see what you find and then let’s have a talk at night.” Evening, I went and told him I said, “I had been to these three locations and I attended some meetings of your Pani Panchayats in these villages and the thing is totally run by contractors, not by the villagers. The villagers are all on paper and money is being syphoned off.” So he said, “What should we do?” I said, “There is a way of setting up these systems of Pani Panchayat. If you go and you give a speech and you get people excited that they can build a dam and they can form their own committees, submit an application to you, it doesn’t mean that they’ve understood what you said. There’s a way of organising the Pani Panchayats.” So he said, “Okay, then tell us what to do.”

We then ran this programme, built 144 check dams, all built by the people. How many people from PSI were there? Five. Five people working in 144 villages around Palamur district in Bihar and in two years these dams were built, but the fascinating part was these systems that we introduced for the Pani Panchayats to really own their dams.

MUSIC

And that sense of empowerment that they got… The proof came two years later when we held a Pani Mela across the district and the women came to us in the Pani Mela and they said, “Humko bhi ek manch apna chahiye.” “What happened?” “Yeh purush log humko bolne nahi dete hai. Jab bhi hum bolne ko baat karte hai toh humko bolte hai baith jao. Aur aapke Pani Panchayat mein dekho kitni mahilaein hai.”

So then we worked with them to set up the Mahila Manches in all the villages. They took on afforestation programmes, they took on some livelihood programmes so this is how PSI developed over time.

SUCHITRA

It’s a very interesting view, for you as an individual coming from kind of social and political activism and the institution as well doing this combination of kind of grassroots building and activism but also institutional building. So can you talk to us a little bit about how you built institutional systems at PSI? How did you, did you even plan for succession? How has that worked? Because in the social sector things like succession is a very close to the heart subject I think for most founders.

RAVI

Okay, first I must tell you an impression that I have. I may be right, I may be wrong, but the people of my generation, whether it was Dunu or Bunker or the Raj and Mabelle Arole and so on, lots of them, we came through. We were in a sense self-created leaders. We had an inner drive and we did something that was seen to be unusual and it excited a few other people who then joined us. So in terms of organisation building and planning, there’s none of that in the 70s. You don’t see that in the 70s.

That comes in the 80s, once big government programmes are rolled out and the voluntary sector is invited to take on government projects. And then after that, other international donors joined the bandwagon and big sums of money were being handed out to voluntary organisations. So in the 80s, while voluntary organisations, who then became NGOs, mushroomed all over the place, gradually there was a shift from service to development and development action and projects and writing proposals and writing reports. This is not something that we had thought we would be doing.

So for people of my generation, I would say by and large there would be exceptions, of course, the system’s way of doing things emerges much later, in the late 80s, second-half of the 80s. And I think Pradhan is a pioneer in that.

As I mentioned earlier, I learned these things, the value of systems and management much later in the 90s. PSI had a very nice organic growth for almost the first 10 years. And then we got more and more sucked into taking up projects. People had heard about our work, so they would come to us and say, “Aap yeh bhi kar dijiye, aap woh bhi kar dijiye,” and then we became a bit too large very quickly. And that’s when I felt the need for systems. At the same time I got on the board of Pradhan and I learned how they had organised themselves. So thereafter we began to put systems into place.

But it took a long time to get so-called professional systems into place. There I think the role of the donor agencies must also be mentioned, that they also began to demand. Especially in the 20 years ago when corporates began to give money to NGOs, they brought in their corporate culture ki, “We have to keep these kinds of records. We have to comply with all these regulations.” You know, take for example the sexual harassment POSH, the POSH Act. It took a long time. Even now I would imagine half the organisations in the country don’t know what POSH is all about and they don’t have an internal committee etc. So it’s only, I would say, after the year 2000, that these systems began to come into PSI and the way we work. Earlier it was leadership by example. And I learned the hard way that people… There is no system of osmosis, that just because you live and work in a certain way that everybody else will do it. So systems became very useful at that point.

SUCHITRA

And handing over many people might find it hard to hand over something they founded, right? How did you?

RAVI

Again, I must give credit to Pradhan because I had seen Vijay and Deep Joshi share the directorship alternate, I think a couple of times, and then younger, newer people, professionals coming in like Achintya Ghosh I think came after that, Somen after Somen, Manas and so on, Narendra. So they had developed this system of succession, they had how a successor is to be chosen and they had the Stewardship Council etc.

So at PSI I began to think in terms of succession around 2005. There was a friend of mine, Dr. Rajesh Thadani, who was working with Chirag and he had decided to leave Chirag. I thought that I might try and talk to him and see if he would be interested in taking over from me. But before I do that, I need to check with my colleagues here. So I took some of the seniors out and I asked them.

They were not happy about it except for one person who said it would be a great idea and I asked him, I said, “Everybody saying it’s not a great idea. Why do you think it’s a great idea?” He’s very highly educated. At that time, I was the only PhD here. We’d had some other PhDs in between but they didn’t survive too long and Anil was just finishing his PhD, so he said, “He has run another organisation, a much larger organisation, so he has the expertise and I think that would be good for the institute.” And he was the oldest employee who’d been here the longest until then. Then I started talking to the board and I said, “Look, I would like to now step down. I’ll still continue at PSI, but not as Director. You can start looking for another. They all felt that it should be someone from inside and they chose him. My colleague Debashish Sen, who’s now the Director.

So he was chosen by the board and my attitude was, something that I picked up from Narayan Murthy, that once you’ve selected your successor, then you give that person a free hand. And his successor had been just like Debashish was to me – somebody who had begun with that organisation and grown up with that organisation. So I thought… I told Debashish. I said, “Look, Debashish, I did not have anybody looking over my shoulder telling me what to do and I really benefited from that freedom. I’ll give you the same opportunity. I will not tell you what to do. This is your organisation, you run it whatever way you see fit. If you need my opinion or suggestion, you can always talk to me and I’ll be happy to help.” So that’s the relationship that we’ve maintained ever since then. I stayed on as a staff person for three years after I gave up the directorship. And took whatever responsibility they Debashish gave me. Let him run the show, I got out of the board, I told the board, “There’s no way I want to exert my influence,” and I stayed out. And you know Debashish still, almost 10 years later, he’s still the Director of PSI.

SUCHITRA

Along with PSI, there’s another organisation that you’ve been a strong and kind of silent partner with, which is the Latika Roy Foundation, or Latika, as it’s known now. Can you tell us briefly why it was started and what it does?

RAVI

Latika Roy was Dunu’s mother. She was a self-made woman. She got trained by Maria Montessori and started the first Montessori school in Dehradun. When she passed away, Dunu’s father came and said, “I want to do something for Ma,” he used to call her Ma. I said, “What would you like to do?” He said, “I’m thinking that maybe we have this place where kids can come and learn Rabindra Sangeet. She was very fond of Rabindra Sangeet.” And I said, “Okay.” He said, “I have found a plot, I want to show it to you.” So he takes me to see a plot. And I said to him, “Mr Roy, how old are you?” “About 85-86.” I said, “So when will you buy this plot? When will this building get built?” “What should I do?” I said, “Well, I’ll tell you what we’ll do.” I was fascinated by Bal Bhavan. My formation also, a lot has to do with Bal Bhavan. My love for reading, for example, or playing games, sports and so on.

So I said, “We’ll rent a building and we will set up a Bal Bhavan over there.” So he said, “Okay, good, but I have only two lakhs.” I said, “Good, you give two lakhs. We’ll put it in an endowment, we’ll set up a little society, ‘Latika Roy Memorial Foundation’, and it won’t cost more than…” I did a quick calculation, I said, “Won’t even cost us ₹10,000 a month. I’m sure we are capable of raising ₹10,000 a month.” So that money we’ll put into endowment. And that’s how Latika Roy Foundation started as a children’s activities centre where kids can come in the evening and just come for fun and games. No studies, no books, textbooks or anything. Just fun and games. Lots of kids came, people loved it and so on.

And then Mr Roy started telling Jo, “We should do something for the disabled no? Ma was in the wheelchair for the last few years of her life. Do something for the disabled.” And about the same time we began to realise that our own daughter had a very severe disability and a degenerative kind of illness. So we decided, “Okay let us open another activity here which is Karuna Vihar which is meant to be a place, it’s a school for disabled children, but a different type of school where each child will learn according to his or her abilities.” And so that was the beginning of the Karuna Vihar and bit by bit it just grew and you probably know that there are about 400 odd kids who come to that Karuna Vihar school every day. And I would say that on a monthly basis, they see about 1000 kids a month.

SUCHITRA

So both you and your wife have worked in the social sector for decades, and I know I’ve heard from your children that they’ve told me it made for a great childhood for them – discussions on ethics and justice at the dinner table. What were some of the challenges on a personal or kind of family perspective? Financial, emotional, otherwise?

RAVI

Oay, challenges. The first challenge was of course a big financial and emotional challenge. There was a… See, Jo came from a very close-knit Catholic family. Seven brothers and sisters. She’d never thought about India. She never thought about any place outside of the US, and then all of a sudden she meets me, we don’t see each other for two years, we renew our acquaintance and within days decide that we’d like to get married. But I put this condition before her, I said, “Look, I know I’m not going to live in the US. I’m gonna go back to India and live there. So there’s no question of marriage until you are willing to go to India.” She said, “Yes, I’m willing.” She hasn’t thought about anything, she didn’t know about India, nothing. So for her it was a great challenge to move away from her family and come to India.

On top of that was a financial challenge because both of us had been activists and I had decided long ago that I would not contribute to the defence department of the US and therefore I did not want to pay any taxes, so I deliberately never took up a position which would give me some income that was subject to tax, which meant that I never had any money. And Jo was a full-time activist, a jailbird in case you don’t know, she had been to jail 6 times.

SUCHITRA

Tell us how much money was in your pockets when you came.

RAVI

₹4200. We landed up in India, and I think the customs took about ₹1500 to clear that luggage that came later by ship. And what was it? Mainly books. So we had a really tough time in the beginning. And again, Professor Mehta helped out. I wrote articles for some publications and every now and then Jo would get something published in an American magazine, which paid about $100. And that was like a feast for us. So that’s how we kind of grew up. And even when I went to, when I moved out of Delhi to come to, Dehradun, my income dropped by 50%, so I used to earn about ₹8000 a month over there, and suddenly I’m down to ₹4000 at PSI.

So again, the ethic that I was given, “You learned to live within your means.” But you know what’s interesting is if you are doing good work, your friends and your social circle really help you out. They don’t have to be asked to help you out. You can do that, but very often they come forward themselves. So many of our friends were very helpful in helping us cope with these challenges.

The problem that I imposed on the family was my frequent absence from the family. Most of PSI’s projects were outside Dehradun, and I always wanted to keep myself well informed about how those projects were running. And so I would go on field tours very often. I was out about 20 days in a month and so I missed a lot of the growing up of the children, you know, parent-teachers’ meetings and prize distribution, nothing, I never went to any of them. And all that burden fell on Jo. Jo is much more social than I am, so she’d go to friends, homes and their parties and so on, and they’s say, “Where’s Ravi?” “He’s out of town.”

MUSIC

HOST

We now turn to Dr Chopra’s work after his retirement from the People’s Science Institute.

SUCHITRA

Let’s talk about post PSI, which is now, the past decade of five or six years. What is the kind of work that you’re doing, editing, writing, the Supreme Court appointing you committee on the Chardham case, can you talk about all of that?

RAVI

I first stepped down as Director on December 31st 2014, but I stayed on at PSI till April 2017. I was 70 years old and I told Debashish that I would now step back. If he needed me he could call me, but otherwise I would stay at home. In that period I began to help out other organisations, whoever asked for some help and if I felt competent to do it. So it’s a little bit of consulting work. India Rivers Forum, gave it some attention and helped establish its two-yearly programmes. When they held that programme on Ganga, they decided to publish a book. Then the task of editing, I was one of the three editors of that book which is about to come out now. So I did a little bit of writing when somebody asked for something.

And then came this Chardham case. I had earlier been the Chair of another Supreme Court committee on dams in Uttarakhand. So given that background, Justice Nariman agreed to the suggestion that I should be made the Chairman of the Chardham Committee. So from September 2019 till, I quit in January ‘22. But you can say that most of my activity stopped in January of ‘21.

So I did that. But then in ‘22, this Hindutva and anti-Muslim anti-Christian sentiment suddenly blew up in Uttarakhand. And then I got some friends and said, “Let’s do something.” So I got involved in setting up the Uttarakhand Insaniyat Manch and helping it grow. So this is my most recent bit of organising. And the first programme that we held, we were worried, “kitne log ayenge?” Consensus was, “Hum log 60-70 toh ikhatte karlenge.” I said, “Then we must get a hall that can only accommodate 100 people, not more, so that it looks like the hall is almost full.”

So we did a programme. More than 150 people came. We set up something called the Shanti Dal and 60 people signed up for that and bit by bit, small effort, small activities… . What we have been doing is organising small group meetings to spread the message of Insaniyat Manch and why we need communal harmony in our city. We are focusing on the city at first. What are the values that are enshrined in the Constitution and why they are so important? So the issues of civil liberties, human rights, secularism, etc, all those… So small group meetings that has helped us expand our membership…

SUCHITRA

One thing that you’ve been kind of you’ve talked a little bit about the committee on Chathams and the Committee on Dams, but this whole idea of individuals having an effect or interaction with government and interaction with committees and you know… does it have an impact? People could ask you what, what difference does it make? One report that’s written that comes out or assessment that’s done?

RAVI

See I have been involved with the government at various levels since about 1993 or ‘94. Ever since that Palamur work that we did. We were able to have some impact on government thinking, government programmes at the states and at the central level. Many states we were effective with the state government. But when it comes to these committees, the two that you mentioned, the first one on dams, people very often say, “Kya hua uska?”

Now the case that was referred to the government, to the best of my knowledge it is still not over. But in our report, we were asked 3 questions: Tell us whether dams in Uttarakhand have harmed the environment. Don’t tell us what happened elsewhere. Tell us whether they aggravated the impact of the 2013 flood. And the Wildlife Institute says 24 dams should be reviewed, you review them and give your opinion. So the committee said, “Yes, we have investigated, we’ve gone on the field, we’ve talked to people, we’ve read publications and on the basis of our studies, unanimous conclusion that yes, dams have these negative effects in Uttarakhand.”

“As far as the 2013 disaster is concerned, we visited places where dams led to disasters and aggravated the disasters. So based on field studies, we can tell you that the presence of dams, had the dams not been there, those disasters would not have been aggravated.” “And as far as your 24 dams are concerned, 23 of them should be dropped.” And the most important recommendation was a new one where we said, “There is something called a para-glacial zone in the mountains. River valleys from where the glaciers have withdrawn in the past. They are full of moraines, full of lots of boulders and rocks and so on. In the event of heavy rainfall, the rivers bring all this down and they create havoc downstream. So no dams should be built in the paraglacial zone.”

Now after this, a lot of activists got involved, GD Aggarwal was involved in fighting for the Ganga and it’s the follow-up effort that led to a big change. 70 dams had been proposed in the Alaknanda Bhagirathi basin. Out of the 70 dams, 19 had been built before 2013. Out of the remaining 51, the Government of India is now fighting in the court for permission to continue with seven dams. Their argument is, “More than half the work was done.” And 44 have been dropped. So I think that’s a very, very good achievement.

On the Chardham case, the majority of the committee was packed with either government officials or scientists who work in government institutions and they all voted in favour of what the government wanted. There were few of us who were independent and we voted to follow a notification of the Ministry saying that wide roads cannot be built in mountain areas, because in the last few years, ever since we had decided to build wide roads, the evidence, the experience is that it leads to a lot of environmental degradation, destabilisation of slopes, and it harms public life and security. So in the mountain areas we should build narrower roads. And we had been in favour of that. The report which the government did not want me to submit, I submitted directly to the court and the court accepted. They appreciated the report. They came in favour of 5 1/2 metres width.

SUCHITRA

This is the Supreme Court?

RAVI

Yeah, Supreme Court. But later the government, through a lot of legal manoeuvres, went back to the court and they got a favourable judgement. They did not want to rest until they got a favourable judgement and once that judgement came, it was very clear that there was no way that the high-powered committee could do anything effective. So that’s when I chose to quit.

SUCHITRA

Last two questions as we wrap this wonderful conversation is, looking ahead, what are your hopes and fears for the future of India? And having talked about this with you in the past, I know, what makes you so optimistic for India?

RAVI

You know, in the immediate future, things do look very grim. A lot of civil liberties have been curtailed, people have been put behind bars without being brought to trial for long periods of time. There have been mob lynchings in the country. There’s a lot of hatred that is brewing in society and you know, this kind of social unrest is not going to disappear overnight. The wound is quite deep and it’s going to take a while to heal.

But there is a, I’m forgetting the exact statement, but Paulo Freire in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he says that it is the human condition that it wants to improve its life. So it’s in our nature to improve our lives. And I believe that. So in the long run, I think we will progress to being a better society, nation with better values that I’m convinced of. And as regards your second question, what gives me this optimism? See, one is I keep telling Jo, I used to tell Jo very often, I said, “If you look at society over a longish period of time, then there is progress.” You take India when I grew up, I mean there was such poverty. Average age of an Indian? 31 years. Today we are somewhere around 70-72 years. Big change, right? See the number of school going children. I still remember when we moved to Dehradun, I used to travel a lot between Dehradun and Delhi by bus and every morning 7 AM all these bright eyed kids, nicely smartly dressed and so on, going to their schools, and I used to think about what my father used to tell me about his school, where kids would normally show up with only one… either they had a knicker on or they had a shirt on they did not have both the things on.

So things had definitely changed and when I look at my own life, when I was a kid, I grew up in a middle class family. I’d never dreamt that I would go abroad, that I would have a house, that I would have a car and all that. You know, I don’t know how to drive? Because I thought cars and all are for rich people. So if I learn how to drive, I’m sure I will go out in my car. So that’s for the rich people, I’m not rich, I will not learn how to drive. But we’ve got a house, we’ve got a car, we’ve got everything today, kids are well educated, grandchildren are growing up very nicely.

So the fear that a lot of people have for some reason, many of us, whether it was Dunu, or it was Bunker, it was… Look at Aruna Roy, she quits the IRS to go become an activist. And you think there was an organisation that was going to pay her any money? She didn’t have… . I didn’t know where my money was going to come from. It was a leap into the dark. But there was that belief that if you do good work, people will recognise your work and they’ll take care of you. That’s where my optimism comes from.

MUSIC

We are a product of our times. Over time and 75 years later, after independence, the nation has changed.