E19 - Part 2

Stan Thekaekera: How do you strategically plan to eliminate fear? (Part 2)

This is Part 2. We recommend you listen to Part 1 first.

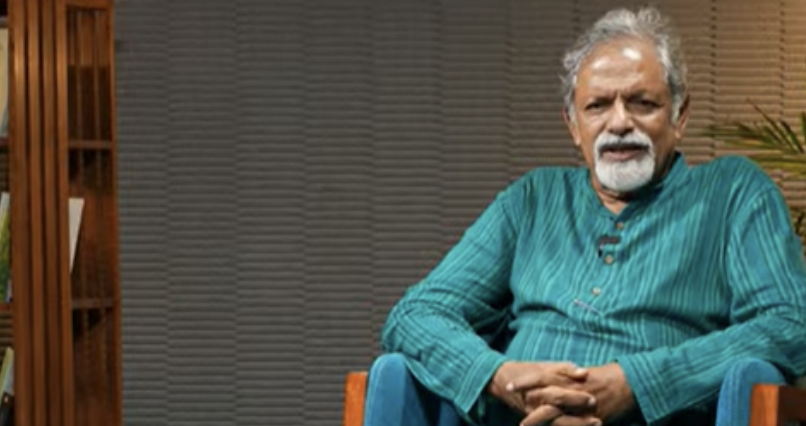

Stan Thekaekara is a social activist who has worked with indigenous and Adivasi communities for over forty years.

He co-founded ACCORD, or the Action for Community Organisation, Rehabilitation and Development and organisation that helped found the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam (AMS), a membership based tribal organisation with 4000 families as members.

Stan is the founder of Just Change, an international cooperative linking producers, investors and consumers in an effort to reimagine a community-based trade and marketing system.

Stan has served as a trustee of Oxfam GB and was Visiting Fellow at the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at the Said Business School, Oxford University.

This is part 2 of a conversation between Stan and Dr. Roopa Devadasan a Public Health expert and school teacher. This conversation was recorded at the Bangalore International Centre in Bengaluru.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

Stan Thekaekera

Stan Thekaekara is a social activist who has worked with indigenous and Adivasi communities for over forty years. Born into a deeply religious family in Bengaluru, Stan found himself grappling with his privilege at a very young age. These feelings, accompanied with his exposure to social action through All India Catholic University Federation, or AICUF, set him on the path to working with marginalised communities.

After stints in Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, Stan and his young family moved to the Nilgiris in South India, where he was involved with mobilizing the Adivasis of the Gudalur valley to fight for their rights. In 1986 he co-founded ACCORD, or the Action for Community Organisation, Rehabilitation and Development.

Through his work in ACCORD, he also helped found the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam (AMS), a membership based tribal organization with 4000 families as members. In all his endeavours, Stan Thekaekara has set out without a larger plan and a belief that the community would find him and shape his purpose. In his life living and working with the Adivasis, he learnt the importance of balancing progress, with cultural preservation.

In 2000, he founded Just Change, an international cooperative linking producers, investors and consumers in an effort to reimagine a community-based trade and marketing system. Stan has also served as a trustee of Oxfam GB and was Visiting Fellow at the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at the Said Business School, Oxford University. Stan is married to Mari Marcel Thaekekara, the journalist, writer and co-founder of ACCORD.

Dr Roopa Devadasan

Dr. Roopa Devadasan is a dedicated Public Health expert and school teacher with over 35 years of experience. She has worked extensively with both tribal and urban populations, focusing on improving health outcomes and education. Trained in allopathy, Dr. Devadasan has continuously expanded her knowledge in various healing systems. She has played a pivotal role in community health programs, particularly in the Nilgiris, addressing malnutrition and maternal health issues. Her commitment to public health and education has made a significant impact on the communities she serves.

I never thought of us having made any sacrifice whatsoever, because what we did we did by choice, we chose to do it. So when you choose, you don't think of having made a sacrifice. When you feel you've been made to do something, you have given up something. In the process, have we not had some things? Of course, but we lived with it because it was our choice. So no regrets, absolutely no regrets.

Stan Thekaekara

Audio:

Journey of Adivasi Munnetra Sangam by Adivasis of Gudalur

The AMS Thaen Kootam (AMSTK) for the Kattunayakan tribe in Gudalur by Adivasis of Gudalur

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

This is the second part of Stan Thekaekara’s story. If you haven’t listened to the first part, we recommend you do so. Stan is in conversation with Roopa Devidasan, a friend and former colleague.

HOST

ACCORD was founded in 1986, over the next few years they worked with the local adivasi youth – who Stan refers to as animators – who were organizing themselves into village level groups, or sangams. In 1988, these sangams federated to form the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam.

ROOPA

And I’m sure in ‘86 you had no idea that the organization would grow into something and that the Adivasi Munnetra Sangham would be born. I mean, there was so much that happened after that. But when you started ACCORD, were you still responding to felt needs?

STAN

It was very simple. First of all, we wouldn’t have started ACCORD if we didn’t have to raise funds. So the fact that we needed to raise some money to support ourselves and to support the four or five young tribals who had joined us, we needed to have an organization, we needed to be a legal entity, as they called it.

So Mari and I looked at various, you know, Memorandum of Association of various organizations. And this was before computers. It would’ve been much easier if you had computers, then we had only typewriters. So from these things, you know, I would read out one thing and we’d say, “Oh, that sounds good,” and Mari would type it up. And then from another one we’ll take another clause. We stitched together a lot of clauses from various organizations, typed it all up in a document. I went to seven of my friends because seven was the minimum. So Mari and I, two of us and five others went to five friends who all signed this Memorandum. I took it to a Chartered Accountant who vetted it, approved it, and changed a few things. And then we took it to the Registrar of Societies and he put one chaap on it, gave us a certificate, and we came into existence.

So till today I mention that ACCORD is a piece of paper. ACCORD does not have a life of its own, it was a piece of paper which was brought into existence through this. And any day that piece of paper can be changed. So we shouldn’t give it importance, more importance than that… It was an instrument that was created because it was necessary. So for us, we had a single point agenda at that time, that was to organize the tribals to get their land back and to stop all forms of exploitation. And that process of forming these village level sangams who would reclaim their lands is what we wanted to do. And hoping that in a period of five to ten years, we would have been able to create a strong tribal organization and we could withdraw. I was a big champion of withdrawal-

ROOPA

I remember that, I remember that well.

STAN

So that was what we started on. And this movement of reclaiming their traditional lands just grew. And I still remember first, when we tried to talk about sangam, all of them could only think of these political sangams from the parties and all that.

So the first sangam that formed was in a village called Kalichal. And we were invited for this sangam inauguration. And they put out a table and they put flowers and everything. I can’t remember, maybe they even had garlands for us, I can’t remember. But there’s this formal thing which was not what we were talking about, but I decided to go with the flow. And suddenly, a few months after that, in one village, what happened was, all the tribals were bonded labor to this Chetty. He had bought a small tractor, and his paddy field was below this village, this village on the hillside. So he wanted to get the shortest route to the paddy field, and he came and cut a road through the village and cut down their coffee and their pepper and everything to make a road for his tractor to go through. Unfortunately for him, the young team of animators who were working with Mari and me, had had a couple of meetings in that village about asserting their land rights and why they have to stand up to this kind of exploitation and why we have to fight against this kind of bonded labor and so on.

ROOPA

Yes.

STAN

So these people went and met Subramani and Bharathan, who were our animators at that time, and they immediately went, they spent the word and before we knew what happened, by 8 o’clock there were about 200 Adivasis who had gathered at this village from all the other villages. And they took a decision that whatever happens, we will not allow that tractor to go past, down this road. Because once it goes, the tractor has established a right. So to prevent the tractor, they dug a trench across the road.

So the tractor driver came and sure enough, he couldn’t cross this trench. He went back, brought Chetty.

Chetty saw this, he went off in his jeep, brought the police, and one young, very active Sub-Inspector or Inspector, came and he started shouting at the tribals and so on. And again, we were very strategic about these things. One of the training that I gave the animators right from the beginning, is you can always predict what they will do, they can’t predict what you will do, so don’t do what they think you will do. Do the opposite. So then they don’t know how to deal with you.

So they had decided, when the cops came and all that, they got the women to like, you know, in English, they say yodeling, “ooOooOo”, the women kept on… So this shook this cop. He didn’t know what was happening because he felt like all these women were booing him, which actually they were. And so then he called up, he knew Bharathan, and he said, “Brother, tell them to at least respect this uniform, if not me.” Then he said, “Then you must respect them.” He said, “You haven’t asked us what has happened, you have just taken the side of the Chetty. You have not found out what has happened. Whose land this is, nothing.” So he said, “Tell me.” Then he said, “We won’t tell you when you are on the other side. Come to this side.” So this young chap tried to jump across this trench that they caused, and he fell down, he couldn’t cross it. And so that was another part of the tribal folklore, that Adivasis had to pull this cop out of the trench. And as soon as he heard the whole story, he jumped back and this time he succeeded, arrested Chetty and took him off to the police station in his own jeep. So suddenly the whole tables turned and suddenly it spread like wildfire. For the first time, the Adivasis had stood up to a local landlord and had asserted their right to the land successfully.

So after that, there was no looking back. Then it was like wildfire, you know, just like a movement everywhere. Then it reached a point where we couldn’t cope because every day we were hearing of Adivasi taking some land and then police coming to arrest them or forest department coming to arrest them, then we were running off to get bail for them, all kinds of things. That was when we decided that now the time has come to make a public statement of it.

But one step before that was we realized that they had the land, but they had no title. So to prove their possession of the land, we decided to plant it with a permanent crop. And we chose tea. Again, I won’t go into the details, but we chose tea because that’s the mainstream economy. And this is something, again, over the years, I fine tuned and understood a lot more, that we are too concerned about creating incomes and we are not concerned about the economy. And very often we train people to be part of a local economy because they are getting income from it, not realizing in that process you are actually making somebody else much richer.

So you are not creating an economy for the people, all you are doing is making them instruments in a larger economy. And so this idea of creating a new economic base for people, not just creating incomes, but to create an economic base for the Adivasis, became an obsession. And looking at that is when we realized that we will help them to plant tea, since that’s the mainstream economy, rather than bring in some peripheral kind of economic activity. You know, you train people as drivers, for instance – everybody’s happy because then they get cheap drivers or cheap masons or cheap tailors. So rather than that, we’ll take a piece of the mainstream economy, which is the tea economy. And then for Adivasis to say, if you ask them, “What are you doing?” To say, “I’m a tea planter”, then everything changes, the equations change.

Everybody laughed at us. When we went to the tea board asking for help and support, he says, “How many acres are you thinking of planting for each person?” We said, “About ten cents.” And they said, “Ten cents? That’s nothing. You know, according to the tea board, 25 acres is a small farmer. So ten cents, what do I say? You’re a micro mini kind of farmer.” Things like that. But anyway, we did it again.

Another long story, but ActionAid was supporting us at that time, and they had the flexibility where we could do various things. And we started this whole tea planting program, which became our flagship kind of program. But then we couldn’t control it because it just was spreading all over. We decided the time had come to go public. Until then, nobody knew this was organized. So this is another very big lesson we learnt. Little bit strategic, we thought of it, but more with hindsight.

NGOs have this thing of waving a flag even before they’ve done something. They put up a board, they have an inauguration, you know. So I said, “You know, what we should really have is not inaugurations, we should have, what do they call it when you’re something? You should have a celebration when you close something, not when you’re going to start something and announce it.”

We stayed very quiet about it. And because the people were mobilizing the villages, where adivasis themselves… nobody was aware. Nobody knew what was happening. Everybody thought that these were disparate, uncoordinated kinds of efforts and they didn’t know that this was all organized, that we are putting these youngsters through an analysis and they were going and mobilizing their people. So we decided that time has come to be public. And so all these village sangams federated to form the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam (AMS) in 1988. And in the name of the AMS, they had this big tribal demonstration.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO ABOUT THE AMS AND LAND RIGHTS STRUGGLE

We were very careful that ACCORD wouldn’t fund it, we kept a distance, but that thing took off. The demonstration, I think Mari would have mentioned also 10,000 people landed up, we were expecting a few hundred. And in fact, the DYSP, when Subramani went to ask for permission, he said “Idhukellam permission theve illai. Evalo per varango? Path per kuda varade. Neenge evalo kudukkare?” (ENG: You don’t need permission for all this. How many people are coming? Even ten people won’t come. How much are you paying them?) He said, “How much are you paying them?” He said, “We don’t pay.” He said, “Then not even ten people will come.” Then Subramani insisted and he said, “Seri, yedithittu po ni.” He gave him permission to hold a protest demonstration.

And since he had officially given permission, he assigned one cop, one policeman to be in charge of this. And then 10,000 people landed up and there was chaos. Nobody knew how to cope with it. There weren’t enough police personnel to handle it. And then they realized the vast majority were women. And Gudulur did not have a women’s police station. So there were no women police so they had to bring somebody from Ooty. But by that time, the road had got blocked, no vehicles could move on that road. Not because we blocked the road, just because there were so many people on the road. So these poor women police stopped 14 km away and they had to walk the whole distance. By the time they reached Gudalur in the evening, the whole protest was over. Everything was over.

And that was a watershed moment because the public speeches were all in their own language. We didn’t speak in Tamil or Malayalam. Each tribal leader spoke in their own language and the town didn’t know what was happening, they had never seen anything like this. But that put the Adivasis of

Gudalur firmly on the socio-political map. So that is the first evidence of an organized community. And that’s changed everything. That’s changed the way everything is looked at and so on.

So we formed AMS and that was the time we were saying, “Okay, this is time for us. We should start thinking of withdrawing. We put this thing in place. Land is there, tea is planted. Maybe a couple more years and we can wind up and all that,” which is when the next big thing happened. And that was when three women died of childbirth in one village in the space of one month. All first babies, preemies, and all three were avoidable. So actually all six were avoidable. So six people died in the space of one month. And then we had this big meeting, “Is this enough, what we are doing? Should we do something in health?” Of course, our experience with the previous organization was so negative, what they were doing there in health. So we didn’t want to and we didn’t have a background. We were doing something where there is no doctor, which is our bible. And then we decided we should do something.

ROOPA

You started a health workers’ training at that point.

STAN

We decided to start a health worker training with Sujatha. We asked Sujatha Dimagiri and she said she’ll come and do a health workers’ training. And we thought, we’ll try and do something which was when, through a common friend, we got in touch with you and Deva. You got in touch with us, I can’t remember who initiated it, but you were planning to get married and you wanted to spend three months before you all went for your postgraduate studies at CMC in community health. And we convinced you to come and spend those three months with us, offering you the bribe of a beautiful place for your honeymoon. And so Deva and you landed up, you came for three months and you stayed for ten years.

And that’s when for the first time, we moved from what would today be called an “activist role.” That time we didn’t have the words for all this, where we started taking on developmental activity, because even the tea planting was not seen as a developmental activity. Tea planting was seen as human rights to protect the land. But the moment we got involved in health, it was trying to do something from a development perspective.

Then it led to education – same problem, none of the children going to school. We got involved with education – another story. Then Rama and Ram Das came to do an evaluation. They did a beautiful evaluation for us of what needs to be done. We just handed the document back to them and said, “Why don’t you come and implement it? You all have thought it all out, so you come and…” So they joined us. And so, like that ACCORD was doing all these things – health, education, economic development, human rights, legal aid, all these different aspects. But slowly this NGO badge started getting stuck on us. We didn’t have a vision of being an NGO, we always saw ourselves as catalysts, we didn’t see ourselves as doers. We were thinking of starting processes. Our whole idea was to start, and our favorite phrase is to “initiate change that is continuous and irreversible.” So it should be a process of change once and then it should go on its own steam, it can’t be reversed. But slowly we started taking on these developmental activities and it. Ever since then, it’s been difficult to keep this balance. It’s a tightrope because one or the other makes demands on you, and when you try to respond to those demands, the other part of the work suffers. You get very focused on the developmental side, some of the human rights issues start suffering. So keeping that balance was not easy for the team. But the thing was that all these Rama and Ramdas, Deva and you, Anita from Ecology, Anu and Krishna as Architects, all of them joined. And we formed this fantastic team, which we again call the support team.

ROOPA

But, you know, I’d like to ask you something here. Because I remember one of the first things you told Deva and me was we really cannot go into a hospital, you know, institutions are a terrible thing to get into because the institution will swallow the rest of the work. And I mean, in hindsight I can see where you were speaking from, but there must have been some reason for you to include those developmental activities. As you said, there was no name for it at that point, it was a kind of response. But looking back, do you think it could have been done another way?

STAN

I am not so sure. I think the thing was right through, from day one, it’s not something that came later. From day one we were very clear that this has to be… Everybody talks about community participation. We were talking about community ownership.

We are saying we own it, but they participate. It’s not about getting them to participate. Whatever else might be your legal structures, decision making is to the community. And so we were driven by that, we were driven by the community making decisions. So we tried various experiments – we tried with the government, you volunteered with the government hospital – that didn’t work. We tried with some nuns with this thing, we tried with a private hospital, we tried with a cooperative hospital in Kerala, in [Sultan] Bathery lots of experiments. And finally we tried starting a one-bed ward in our office.

ROOPA

Yes, that was… And that worked for a couple of months.

STAN

Till that woman died, who you brought into the hospital with no blood at all. So all this led to people suddenly saying, “We need our own hospital.” And we said, “Are you crazy? Your own hospital? Where is that going to happen? It’s not going to happen.” And I fought it on political grounds and also, you know, that we want to withdraw. Hospital means what happens and all that. You all were more on the side of focus on community health.

ROOPA

That was one, and I think we were burning the candle at both ends. Physically, it was impossible to do anything to do both. And we knew that community is what we wanted to do, not the curative part.

STAN

But then we had that big sangam meeting where all the sangam leaders came. I still remember that we sat on the hillside behind the office. At the end of the day, everybody had made a decision that we should start a hospital, and we had to respect that decision, however difficult or impossible it seemed. And the next day, when the smaller team met to see the next step, they were saying that the two specialties we need as a starting point is to find the doctors – we need a surgeon and a gynecologist and both who are willing to do GP work. And I laughed and pointed down the hill and said, “Can you see the long line of GPs and surgeons waiting to come and work over here?”

ROOPA

Come and work with us.

STAN

And believe it or not, could be Mari’s mothers prayers being answered, or could be that somebody up there is looking after us. Within the week, we got this postcard from Nanda Kumar saying that he’s returned from the US and his wife is a gynecologist, he is a surgeon and he’s from Vellore, so he heard about you all from Vellore. So he wrote to you all and said he wanted to come and talk to you all about the possibility of starting a rural hospital. And that’s how Nanda Kumar and Shaila landed up. So they came with a very different vision or plan. It had nothing to do with Adivasis, anything like that. And one of the things we maintained is that even though Deva and you came with a focus on health as a sectoral kind of thing, Rama and Ramdas came with education as a sectoral thing, Anita came with environment and so on. What we successfully did was put the community in the center. So one of the things that many people asked us is, have you ever thought of scaling up? And I said, “No, we didn’t scale up. It’s not horizontal, it’s vertical. We went deeper and deeper into the community, responding more and more to their needs, and we are driven by that.”

So, cutting a long story short, we went down that path of creating community institutions. So in ‘98, I think it was, we had this big mahasabha where we discussed, where were we when we started, where are we now, and where do we want to go. And at that mahasabha, everybody said, like the hospital, we should have other institutions of our own for marketing, for this thing. So this whole journey ended up with us, the AMS, being the hub, and we have these different satellite organizations which provide specialist care to the community. And so till today, 95% of the team in all the organizations are from the community, the boards of all these organizations are from the community and it is totally and completely community-owned and community-run and community-managed. All of us professionals, if you want to call us, or whatever, who have come from outside, played a couple of very clear roles – one was bringing in inputs in terms of training, in terms of new ideas, in terms of new opportunities, and secondly, in terms of trying to locate funding for various things that the community wanted to do.

So a few clear roles for us to play, and we made sure that that was all we were going to do. We were going to play supportive roles. And that’s why we called ourselves the support team.

ROOPA

I’m going to ask a question which is really not part of this, but you’ve been talking a lot about how the organization grew and how the structure was. What do you think was the effect of all this on Adivasis in the community? I mean, how would you look at it from their perspective?

STAN

Yeah. Now, the best thing I can say for this is, I think it was about two or three years after we were into this work… CEBEMO, which is a Dutch organization, had provided us the first funding before ActionAid came into the picture. CEBEMO came to do the so-called donor evaluation. Of course, we were nervous, it’s the first time evaluation was being done, so we were talking to people, took them around to the village. We were sure that in the villages people would say, “Oh, we found a sangam, we’ve got tea plants, we’ve got healthcare.” This is going to be the thing that people are talking about, because these are our flagship things, especially the tea planting and the fact that they got the land back.

But in village after village after village that whole day, and I was with them, the first thing people said, “We are no longer afraid, our fear has gone.” And that’s something again we have maintained over the years. We said, “How do you strategically plan for eliminating fear? And how do you then measure fear?” Can you measure it and put it on some matrix for it to say that this is the fear that has gone because this is a lived experience of the community. And in all our evaluation and monitoring, so many tools now that… Every Tom, Dick and Harry is coming with a new tool for evaluation and monitoring and now every other day there is a webinar on how to improve your evaluation and monitoring. And the latest is now how to use artificial intelligence to monitor your work. This goes on and on. Good, we should do it, I’m not saying no. We are using large amounts of money, we have to be accountable. But in our process of trying to understand change that’s taking place, these numbers are not going to really tell us about the change.

The change can only come if you listen to the experiences, lived experiences of people. They will tell you what has changed. And for us the biggest thing has been people saying that they are no longer afraid.

And recently when we asked young people, you know, school going and just out of school kids in some of our youth camps, when we asked them, “Are you all afraid?” “No, we are not afraid.”

ROOPA

They probably have to be told the history of their people though…

STAN

Exactly! We have to tell them what it was, what their parents felt, what their parents went through, and they can’t understand it. They don’t understand because they are not actually… They are going to school now, their best friends are non-tribals, they are not running away from non-tribals. They are having birthday parties, they are going to birthday parties. And so there’s been a huge sea change.

So one of the things we had stated in ACCORD right in the beginning when we wrote the first formal proposal for ActionAid, they asked us to define what our vision statement is. So we said that, “Adivasis should be able to participate in mainstream society on equal terms, with their own dignity on their own terms, to participate in society with dignity and pride on their own terms.” And now that is what is happening, that they are participating.

Yeah, so this whole ecosystem has been set up. Proud to say that it is 90% managed and run by Adivasis themselves, they are in the driver’s seat. Because of that you can find fault with their decision making – they are much slower, their processes are through consensus, not through a vote. So many donor agencies find that very difficult. They send us an email and say, “EoD, can you give us a decision on this?” And first I had to find out what EoD was and then I realized by the end of day, they want a decision. I said, “How is it possible? We have to bring together people from different villages and they have to talk. End of day?!” So I started sending EoW. Somebody asked me, “what is EoW? Is it the end of the week?” I said, “No, end of whenever.” It’ll happen when it happens, I don’t know when it will happen, because there’s a process that has to take place, and the process is far more important than the outcome. You want an outcome, and so you shortcut a process and that shortcutting is what refuses or prevents ownership of the community.

You can’t, there’s no shortcut to it. You have to honor it, respect it, and steadfastly hang on to those processes. And so when people ask me about, “How do you know this will be sustainable?” In our sector, every few years, there is a buzzword. Sometimes it’s gender, sometimes… At one point, it was sustainability. So every person came and asked us, “How do you know this will be sustainable?”

So this S-word was thrown to a group of Adivasis and we decided we’ll only be translators. We won’t answer any of the questions because it was meant to be a consultation with the community. Pin drop silence because first we had a problem translating sustainability. Finally, when we succeeded in translating it and everybody understood it, pin drop silence because nobody had ever thought about it. And then somebody gave me what I felt was the final word on sustainability. And he said, one of our tribal leaders said, “If enough people believe in it, it will be sustainable.”

ROOPA

Amazing.

STAN

I believe that that was the final word on sustainability. And this is in our early years, so we have followed that principle of ensuring that everybody is on board. But that all takes time, that all takes time. You need to convince people sometimes. So fear now takes a new form. Not the old form. So now the youngsters have to come out of things that they are currently afraid of, which they may not even be aware that they are afraid of. So new things have to happen.

I’ll just say one last word on change, and then maybe more on other questions. When I was on the board of Oxfam, this is something I raised over there – we are so hung up on change, all of us, and we all look at everything through a poverty lens. So you want to change things for poor people. Okay, so alongside that, we make these assumptions that therefore poor people are incapable, so we have to build capacity. That’s another word I hate, because there’s an assumption that they don’t have capacity, and we have to build capacity, without defining what capacity, why, for what – nothing. Just build capacity. “Building” is one of the buzzwords.

The second buzzword that comes out of this attitude towards poor people is “empowerment”. This is a word that’s forbidden in any of the ACCORD literature. Because empowerment is a politically loaded word and if anybody who studied Paulo Freire would understand it – because you are assuming that you are going to give power to somebody. And we have maintained that power is about relationships, so it’s finite, it’s not infinite. It’s not like I can hold on to all my power and then empower you. If I truly want to empower you, I should give up some of my power, because this power is defined by our, determined by our relationship. So when ActionAid and a couple of others asked me to do some evaluation of projects, you’d find that that was when we moved from sustainability to gender to empowerment.

So when we moved to empowerment, everybody in their proposal… I used to tease the donor agency, saying that, “I know how you all sanction proposals. You have a keyword, and then you do a word search on the computer, and if that word is repeated enough times, you grant a proposal.” So empowerment was a buzzword, and you had to have it on, like every third page, “empowerment” had to appear. So when I found evaluation of organizations like that, the first question I would ask when I went over there is, “Don’t tell me who you’ve empowered, tell me who you’ve disempowered.” They said, “No, we have not disempowered anybody,” because they thought this was a trick question. “No, we have not disempowered, it’s a win-win situation.” So I said, “Nonsense, if you want to empower women, men have to have given up power. If men have not given up power, where are women… Can they go to the market and buy two kgs of power from the market? Or could you as an NGO give five kgs of power to each woman? It’s not possible. Power is a relationship and that relationship has to change. So tell me how the relationship has changed, then I’ll know whether somebody has got power or not.”

There’s also this feeling that we have to change everything because they are living in poverty, everything is bad, everything has to be changed. And we never look at what it is that we do not want to change in these communities. Having lived and worked with Adivasis for so many years, I realized there is far more that need not change and should not change than what has to change because they have a value system, they have a way of living, they have a culture, they have knowledge, they have so many things that should not be changed or should not be lost. And in our drive to bring them into what we called developed mainstream, this is what they sacrifice.

ROOPA

They would probably write the chapter on climate change.

STAN

Yeah, absolutely. On climate change, we have a lot of experience with that and we are trying to do some work around it. So one of the things we are doing is we are doing a major tree planting. We are shifting from a… Like I mentioned earlier, the important thing is to understand the economy. So what we successfully did was to move these people from a daily wage economy and in many villages a bonded labor economy to a plantation or a tea planting economy. A shift took place, we created a new economic base and that’s why we brought about major change, because it was across the whole community. Now the tea planting economy is in the doldrums for a variety of reasons – land holding is not growing, so it’s not going to support the next generation. So what is going to be the new economy? And after a lot of discussion we came up with this idea of why don’t we go back to creating a tree economy instead of a tea economy? And so now we are planting trees.

In our first proposal, when you were trying to raise some money for this tree planting, they were saying, “But you have not put any money there for creating awareness about planting.” I said, “We don’t have to create awareness. This is something that everybody wants, everybody, every village, every family is asking for it and they all know all about it. We don’t have to create any awareness, we don’t have to do any capacity building, we don’t have to do anything. We just have to make it practically possible.” And so now that’s become a movement. Now every year, 5000, 6000, I think next year will be about 10-15 thousand trees – the tea planting people are asking to plant trees in all the villages. We’re not making a song and dance, we’re not talking about this big, you know, greening of the valley kind of thing that most NGOs would have capitalized on by now.

And then maybe since I’m on the subject of economy, I should also talk about one of the things we realized after we planted tea was – it’s great, it changed everything, but then you have to sell the tea, okay? And so there’s a whole thing called the market economy. So then we had to get into that. Again, a long story. We’ve done a lot of things to try to market their products, especially the honey, which the Kattunayakans collect – they were getting totally, totally exploited, they were getting nowhere close to the real value of the honey. So we started aggregating the honey and created a society for them to sell the honey. And once we got into that, we realized there is yet another economy because we had a creative agency that was helping us with this whole marketing thing, and through them we have learned there is something called the brand economy now. So now we have to create a brand, without a brand, we can’t sell our things.

When we started collecting the honey from the Kattunayakans and aggregating it, after the first year, second year, I discovered the wax has almost as much value as the honey. But I didn’t see any wax around. So the next meeting, I said, “Where’s the wax? Why are you guys not bringing the wax?” They said, “We left it in the forest.” As usual I assumed that oh, these people don’t know. So I am trying to teach them that wax has a lot of value, you should bring it from the forest. “No, no, no, we can’t bring it from the forest.” I said, “Why?” They said, “That’s the bear’s share.” I said, “What do you mean by bear’s share?” And then they told us the story of how the bees, the bears, the trees and the Kattunayakans have a pact.

The bee asks permission of the tree to build a hive, and then tells the tree that the bear and the Kattunyakan will also come, and only then will they build their hive. The Kattunyakans come, do a puja, ask forgiveness of the bees, ask forgiveness of the tree, and promise the bear that they will leave the wax so as not to attack them when they are collecting the honey. That’s why the bees never sting them, they never fall off the tree, and the bears don’t attack them. And so we can’t touch that. That’s a promise we made long ago, a pact we have with the bears to leave the wax for the bears because they will lick the wax and they dig out the grubs and so on. So that’s become our brand.

The first share is for nature, which is the wax they leave back. And this is not only in honey, it’s when they take tubers from the forest, whatever they do, they leave back for nature. There is this concept that they have to regenerate, look after nature. The second share is for the people who depend on nature. It’s the honey the children will eat in the house. And it’s only the third share that is available to you as a consumer. So not all the money in the world will allow you to get more than one share. You are only allowed the third share. And for me, in today’s context of climate change, this is such an important message to a capitalist, wealthy society, that just because you have money doesn’t mean you own everything. You’re only entitled to one share of what there is to offer.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO ABOUT THE AMS & HONEY SUPPLY CHAIN

ROOPA

Yeah, I think you’ve stated very clearly the philosophy and what kept you going along the way. Have you ever had moments of doubt or anything that looking back, you might have done differently at all?

STAN

One of the things I feel was a mistake or oversight on our part was assuming that the work that we had done with the young people of the eighties would naturally carry on. And it was a shock to us when we realized a few years later that today’s young people don’t know anything of what their parents did. It hit me when I was taking a session for young nurses who had joined our hospital, and one of them is Badchi’s daughter who has come as a nurse from Kanjikuzhi. And when we’re asking the girls, trying to see what they knew about the history, AMS asked, “How many of you all have tea?” Nearly all the hands went up. I said, “Where did your family get this tea from?” Blank faces. “Illa adhu yepome irundudu.” (ENG: No, that was always there). “No, my grandfather, I think, planted it.” No one knew about the struggles. I was shocked to find that Badchi’s daughter… They fought against Unilever, Hindustan Lever estate because they planted some tea, and the estate came and uprooted all that tea, and there was a big fight.

Again, a long story. But in the struggle there were only women in the village and Badchi was a health worker. She stood up to the government – revenue department, police department, state officials and forest department. So there were about 16-20 men and there were these handful of women who stood up with these men and were protecting their plants. They said, “These are our children, we won’t allow you to murder our children.” And in the scuffle she fell down and cut herself on a tea bush and started bleeding. These fellows panicked and all jumped into their jeeps and drove off. But then she was carried to the hospital and again, long story, but before we knew what happened, there was a huge protest, people from all the villages came and this became a big issue.

Now this girl didn’t know that her mother had done this, that her mother had stood up to a multinational company, had stood up to all the officials and protected their land and their tea. They have tea because her mother stood up that day. She doesn’t know that story. So we suddenly realized that a whole generation has grown up not knowing the sacrifices or the struggles of their parents. And then when I started trying to understand this phenomena, I realized that this is not unusual, it’s a very common phenomena.

When people come out of oppression, they want to protect their children from that and so do not tell their children about the oppression they have suffered. So many of these young people have no clue of what their parents went through, let alone their grandparents. And so this is why we have started a whole thing.

We made a film now for young people made by a couple of young Adivasis on the whole history of what has happened, because young people should understand what is happening. So looking back, I would say that if we had a better awareness of these kinds of processes, we would have ensured that the next generation was also carried along this journey. We just thought, naturally they will be there and they didn’t, we missed them.

ROOPA

The other thing I want to ask you is that I can see the critical thinking and the training of the animators at that time with the given situation of the economy, the political environment, their own situation is so different from what it is today and that role that you play as somebody who catalyzes the whole questioning, is that something that you know, every generation kind of produces for itself, or is that something that people get trained in or how does that work?

STAN

Generally, in society, the dominant elements of society ensure that that is the narrative and everybody follows that narrative unthinkingly. So today, we are living in a very Western capitalist kind of worldview. And that is the dominant worldview, and we all follow it unthinkingly. So now the young Adivasis have moved into this modern economy. If we want to be a catalyst for change, what we have to do is to create tools by which critical thinking can take place. Because the mainstream doesn’t allow you to think critically, does not give you any tools by which… What does school teach you? School teaches you to accept the status quo, not to question it. So what we have done now in Gudalur is we have developed what we are calling the Social Analysis Toolkit, because the animators have found that the analysis they did 40 years ago is no longer relevant because the situation is so different. So we have developed what we call the Community Resilience Framework.

This was a long process, lots of meetings, lots of discussions, and we evolved – “What is it you want for the community?” And so a framework has been developed which has six pillars that will lead to community resilience. This grew out of the kind of almost humiliation that Mari and I felt as Founders, if you want to call us that, that after so many years during COVID we had to distribute food. When we mocked people who distributed food, you know, we said, “We shouldn’t distribute food, we should enable people to be able to have their own food.” You know, it’s not this charity kind of thing. And here we were forced to give food during COVID. So that led to a big discussion of, “Why is it that only the Adivasis required food distribution and maybe a few dalits?” Why is it none of the… We are all saying, “Oh, we are now part of mainstream society. Our children are going to school with the non-tribals. But why is it that the non-tribals didn’t need food and only we needed food? What’s gone wrong?” That led to this development that we have not built something that is resilient.

So then the discussion was, is it only economic resilience? Is that all that is required and this creation of a new economy, or are there other aspects? And they said, “No, no, there’s much, much more, because we shouldn’t lose what we have.” And so we come back to what is it we won’t change and what will it. So the Community Resilience Framework hinges around building unity in the village, the cultural identity, so people are proud of who they are. That’s one very big element and that will underpin everything else, that is like the foundation.

And then you have economic resilience– economic resilience is where everybody will have enough of an income to meet their needs. And now here’s another very, very important word, “enough” of their income. So that’s another subject altogether. So we are built on a concept of creating enough, not accumulating, whereas the entire modern economy is, you accumulate as much as you can. So we have a concept of minimum wage, we don’t have a concept of maximum wage, get as rich as you can. Here, no, Adivasis have a concept of enough, because that’s what keeps the planet in balance, because you don’t suck everything out of the planet. Gandhi’s thing, “Enough for every man’s need, but not enough for one man’s greed.”

The third pillar is in health and here we are focusing on not about managing illness, but about having good health, which is what all our early years of discussion were about. And when you are talking about health now, one new dimension that’s come into play is mental health. That was not so much a dimension when we first started the health work, but now we are finding alcoholism, suicides are all a result of mental health issues. So how do we create mental health also? But for a variety of reasons, we became very centralized. We want to go back to the original vision.

Let each village make a budget. And we are already talking to some of our donors and saying, “Are you willing to give money directly to the village? We will form our village into AOPs, we will let them form their own Memorandum of Association, let them have their bank accounts. We’ll create…” and this is where I don’t mind using artificial intelligence or technology or whatever, and create accounting systems to manage all these finances. But let each village make their own decisions. Why should we take decisions anymore after 30 years, why are we making decisions? Let them decide.

And so then the animators, who we have, who have already put in 30 years and more, and who are all becoming very aware that they are catching up with me, and they’ll have to soon kind of take a back step and retire, we are saying, “What is your vision?” And so they’re also looking at, “Over the next five years, we should ensure that in every village, there are young people who’ll take over.” Rather than creating another ACCORD or another organization. So the animators then already, they’ve already started moving from being implementers to becoming mentors.

ROOPA

I’m remembering the old leadership, you know, the old woman, Chati, Subramani and all. And I remember in some meeting, somebody saying, “We know the old ways, but the new problems that have come are something we don’t know how to deal with.” So it is important that you young people…” That was a time when some of them were really young, Ayyappan and all were playing volleyball. They sort of saw the need for this young leadership and supporting the young leadership. I remember that it was very powerful… It gave the young leadership at that time a sense of stability, because they knew the aged, the wise ones were behind them, and they would be questioned if there was something this way or that. It’s a very interactive thing in the handing over of the leadership. So having gone through that, one just has to remind them that, you know, their time has-

STAN

So this has crystallized, this has crystallized and developed into a strategy. So, 323, if I remember the number right, young people have been identified in all the villages who are going to take the leadership forward. A lot of work is going on there, we are planning, more structured approach of helping them to develop their critical thinking and so on.

ROOPA

And the heart will be very important because the process is more important than the schema, I suppose.

STAN

So that’s why we’ve always, as you know, Roopa, from the beginning, we’ve always focused less on skill building and more on building values and attitudes and mindsets, that’s more important. Skills can be acquired anywhere along the way, skills are not a big issue for me. For me, we have always felt that it should be about building the mindsets.

ROOPA

I think that’s something I have inherited from ACCORD and taken into all my work after that, whether I’ve worked with children or with health systems – this understanding that the value and the mindset of being able to do something for people in a particular way and respecting certain things, I think that’s been very important. Stani, to wind up, looking ahead, what are your hopes and fears for the future of this country? Just putting it all together, what do you feel are some of the hopes you have for the younger generation and some of the fears which you think they might need to face?

STAN

This is not an easy question to answer because it’s a question of at which level we are talking about, you are looking at the community level. The hope is very clear, the hope is that we will be able to help this generation value what they had and not throw the baby out with the bathwater because while helping them to become part of the mainstream or dominant economy by going to school, for instance, or, you know, getting better incomes, the price they are paying is they have given up on lot of values that they had.

ROOPA

Yes.

STAN

So how to ensure that they are aware of those values and hold on to it? So, to give you one example, we have started something called the Adivasi Innovation Hub, which is to help the young Adivasis… Because this came from the Adivasis that they wanted to become part of the modern economy, but not as laborers. So we said, “Okay, then let’s help them start enterprises.” So we started the Adivasi Innovation Hub as an incubator to help young Adivasis start their own enterprises, but when we were designing it and planning it with the community, we said it has to reflect Adivasi values. So we tried to see what are the values that would make this enterprise distinctively Adivasi, as against any other enterprise in a mainstream society, and we came up with three things.

The first is, it has to be a collective, the second thing is… When we were planning this, the story that somebody mentioned was when they go for a hunt and they get the meat, or if they go fishing, or if they go to collect bamboo shoots or mushrooms, when it comes back to the village, it is shared with everybody in the village. Whether they went for the expedition or not, it is shared equally with everybody in the village. So he said, “Whatever we get, we should be able to share with the community.” So then the discussion is – how and where? Because when you get crabs or you get mushrooms, it’s easy, you divide in and it’s in your village. But if you are ten of you, all from ten different villages, and what you all are getting is money, how do you distribute it? So they said, “We’ll go case by case, we’ll decide.” But the principle that we have to divide must be there.

ROOPA

That’s amazing. This ability to not need to plan to every level of detail is so Adivasi. It’s so distinctive, so practical, no? Very practical.

STAN

In fact, the actual words that they said during that meeting was, “Adu vereppu naaluku kaanaam – [we’ll see to it later]. We still don’t have benefits, so why do you want to discuss how to get the benefits?”

And the third thing they said was, “We should not destroy nature, nothing that will harm nature.” So these are the three principles on which any new enterprise… So we are catapulting them into a capitalist economy through enterprise, but ensuring that traditional values are protected. So when you were asking earlier, you know, looking back, what do you regret? One of the things we regret is that we didn’t do this successfully.

We have not kept this balance between traditional tribal values and a modern society. We have not succeeded in keeping that balance – it’s got all tilted into a modern way of thinking. So now, in our interventions going forward, we are trying to ensure that we keep that balance. So, looking forward, the hope for the young people is that they will not lose a sense of who they are as Adivasis, that they will be proud to be… Fortunately, they still are. Externally, they’ve cut their hair, they have these latest hairstyles, they wear the latest clothes, they’ve all started buying bikes, they have the latest phone. But you get them in a room together and start talking to them and you find how Adivasi they all are, they have not given that up. They are proud of being Adivasi, they may not articulate it as being proud, but you can see… Now we have to give them the confidence to articulate.

ROOPA

What strikes me is that when you said one of the pillars is just a sense of community, most of mainstream society doesn’t have a sense of community at all, right? So there is actually, rather than these people going in that direction, it has to go in reverse. It’s just that the numbers are so unfavorable to a smaller segment of-

STAN

And it is going to be the undoing of our human society, because of the greed that comes… And undoing human society, not just in terms of our social relationships, but in terms of destroying the planet, because you can’t have that accumulation of wealth without destroying the planet. The two things don’t go together. So somewhere this concept of enough has to come in. We don’t have that concept and that’s what gives me sleepless nights. Will we have the wisdom to realize that we can’t grow forever? That not growing doesn’t mean that you’re dying, not growing means you’re living, because when you’re growing and growing, you’re not necessarily living.

Finally, to end, a couple of things I’d like to say also is that when I said about what we won’t change, we don’t look at that. So one of the early things, when we were setting up ACCORD was… Because we had no experience, I mean, I have no management background, and that’s why Deva played a big role in this. But one of the things we looked at is what should our organization be like when you’re setting up the organization? So one of the first things we said was, “Nobody will have chairs like this, you know, Director’s chair, no positions, no Director’s office, nothing like that.” And we just borrowed everything from the Adivasi way of doing things.

One is being very, very flat. I mean, a lot of people say we are a flat organization. There’s no hierarchy. But the first thing you encounter when you reach that organization is the hierarchy, but being flat doesn’t mean just in these, of course, the visible manifestations of it, but also in relationships. In your relationships, are you really flat? Now, I find that we have unequal relationships, but this is given my age, you know, Mari and I, they call it Mari Chechi, and have a lot of respect and concern for us. And you know how in India, everybody respects old people, and I’m just wallowing in it. I am wallowing in this respect that we get for old people, but that comes from another place. That’s not institutional, it’s not organizational. So the thing of keeping it very flat, non-hierarchical, decision making to be by consensus and involving everybody in their decision making.

And a lot of people talk about transparency. There’s a transparency international, there are all kinds of things. And my question when everybody says, “We are very transparent.” I say, “How many people know your budget?” Simple question – how many people in the community know your budget? And you’ll find nobody. We have copies of our budget lying all over the place, we’re encouraging everybody and the team to share it with the people in the village, let everybody know the budget. And that’s the best way to hold people who are managing the budgets accountable, that you make it public knowledge, and not stuck in some file or in some computer.

The other thing is resolution of conflict. So now there are so many systems, they want a committee for this, committee for that… We follow the tribal this thing, of, when there is conflict, everybody starts talking about the conflict. We are violating all the modern norms of privacy and all the guidelines that are given for this because everybody talks about it and we encourage people to talk openly, not behind people’s backs, and create more problems. Talk openly and then try to bring about a resolution. And that is the role of the leadership in the communal group that they have to resolve, you know, take that responsibility and bring it to a conclusion. And when there isn’t sufficient leadership is when these conflicts are not resolved.

When conflicts are not resolved, that means there is a vacuum in the leadership and that we are seeing both at the village level and at the organizational level, there is a vacuum. So for me, the ability to resolve conflict is one of the best indicators of leadership. And talking about leadership, that’s another thing, that the whole western concept of leadership is, the NGO sector in India’s lock, stock and barrel is about building leaders, like individual leaders.

We are not talking about building leaders, we don’t want somebody who is then seen as the hero of the village or of the community. What we are building is people who will actually be catalysts within the village, people who will help take responsibility, people who will be like that. So it’s not about building the kind of leadership that everybody else is talking about, it’s about building a very different kind of community based leadership. That’s very different, that’s very different from this individual based leadership.

So one of the other questions, and we were talking yesterday, you asked me, before we wind up, you asked, what are the sacrifices you would have made for this journey?

ROOPA

I did.

STAN

I never thought of us having made any sacrifice whatsoever, because what we did we did by choice, we chose to do it. So when you choose, you don’t think of having made a sacrifice. When you feel you’ve been made to do something, you have given up something. In the process, have we not had some things? Of course, but we lived with it because it was our choice. So no regrets, absolutely no regrets.

Obviously, the clearest and biggest partner was Mari. If it was not for Mari, I would have probably still been in Bangalore, and I don’t know where we would have been. And this is something we’ve advised many young people who have joined us or who have been mentored to set up. The first advice we give them is make sure you get a partner who shares your value system. Because if they don’t, they’ll never understand what you are doing, and there will always be conflict. So if you both want two very different things, it’s a recipe for disaster. And if both of you can be involved, nothing like it. That will bring with it its own problems, there’ll be a lot of tug of wars, and that’s why in our team, we’ve been criticized for it, actually, because we’ve encouraged people to get married.

So somebody who’s working as an animator, his wife is a nurse in the hospital, or somebody who’s a teacher in the school, her husband is working as animator. And we have encouraged this, we’ve encouraged people to be here because we feel that it’s better for couples and families to be involved rather than individuals.And the thing is, we also bring different perspectives.

I am sold on the Adivasi cause for me, it’s not a sectoral thing, it’s not health, it’s not developmental, it’s social justice, so there’s all these big terms and all that, but you need to keep grounded, and it’s very easy not to be grounded. And that was where Mari has played a tremendous role in keeping everything, because she always saw the individual, whereas I tend to see the community or the larger issues. So she was always able to… She would tell me, “Listen, Chathi seems to be having a problem, why don’t you go talk to him?” Or she herself would call them over for a meal and having the animators home with us, sharing food with us, staying with us, all these kinds of things, and being open to them and welcoming to them and all that made such a huge difference in the early years.

So one of the regrets might be now, looking back, is that we are not able to do that much because our circumstances have changed, their circumstances have also changed. We don’t have the closeness that we had 20-30 years ago. Possibly it’s a good thing, I don’t know, I’d like to believe it’s a good thing.

ROOPA

I don’t know whether it’s a good thing or bad thing, because, I mean, I’m thinking that during those ten years, we practically lived in each other’s houses.

STAN

Yeah. So like I said, we made a choice, so I don’t have a problem with that. And people said, “But then how do you manage your work life balance?” If your life is your work and your work is your life, where does this issue of work life balance come from? Because you made this choice.

Recently, talking to somebody who’s joined us and convincing her to think of the long term, she said, “Yeah, I’m here for the long term.: And I said, “So when you say long term, what are you thinking of?” She said, “At least three years.” I said, “Three years is not very long term in the life of a community.” But then she said, “I have to think of my career and professionals,” and things like that. So I was trying to talk to her and explain, “Can you think of a vocation rather than a career, can you think of a vocation rather than a profession? And if you look at it as a vocation, then you don’t have a problem, then time is not, it’s not how many years, it’s what you do with your vocation.” How do you find meaning through your vocation?

No, but again, one of the things I am convinced about when I look back is what has been central to everything we have done has been – people. Whether it’s people from the community, whether it’s people in the team, if it’s the so-called professionals who joined us. Nothing would have happened if we didn’t have people, money comes second. So when there is clarity of what you want to do, you attract people who share that clarity. When you got those people, then the funding will also follow.

A few years ago, for me, everything was black and white. You know, I was on one side of the fence that was with people who were exploited, facing injustice, were poor, and the other side were the rich, privileged people. And, you know, the twain shall never meet that kind of thing. Today I realized life is not so simple because you have some real crooks who are on this side, who you want to have nothing to do with. And on the other hand, you have such good people who might be in that position of privilege by accident, by inheritance, by so many other ways. So the challenge is, how do we build bridges? How do we build communication channels between these communities? And we don’t think of communities only as poor people, only as exploited people, only as marginalized people. But we look at it as humans and see how we build… And that is what will help us to create a new world or a new society. Without that, without these bridges, what’s happening is they’re trying to create more and more chasms, more and more divisions. And I think our job in the sector is to create more and more bridges so people can transcend these divisions.

ROOPA

That’s 50 years, that is coming from 50 years. I think it was always there, but you’re seeing it now.

STAN

Done, I hope.

ROOPA

I was listening as though I was listening for the first time and it was quite fascinating. Because having been a part of the journey, I still had questions that were coming fresh to my mind and you’ve answered them all so beautifully and honestly. So it was a pleasure, thank you.

STAN

Thank you.

HOST

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode.

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.