Winner of FILA 2022 Grassroots Philanthropist, Nilekani props up causes that others may find risky, and steers her philanthropy by having an ear to the ground, operating from a place of trust, and being liberal with her time for the causes and people she supports

By Divya J Shekhar, Forbes India Staff

It was less about the money and more about the intent.

Kuldeep Dantewadia has a clear memory of that meeting with a philanthropic donor in the latter half of 2019, which was scheduled for 45 minutes, but lasted over 1.5 hours. Dantewadia, the co-founder of Bengaluru-based non-profit Reap Benefit, was building a community of citizens to solve problems in their local wards and neighbourhoods.

The donor asked him questions about his non-profit model, not from a place of criticality, but curiosity. She wanted to know how Dantewadia planned to translate individual actions to collective problem-solving in order to bring about larger societal change. She was curious about how women were solving local issues vis-a-vis men, and whether Dantewadia’s team encouraged diversity, not just in terms of gender, but by being inclusive of people of different languages, regions and socioeconomic strata. “She made me think deeper about my own work,” Dantewadia recollects.

What he felt more heartened by, however, was that when he was leaving, the donor inquired about his mental health, something nobody had done before. “She said, ‘You look tired, are you sleeping well? Do you take breaks?’ It was refreshing to see somebody ask me that,” he says. “I came out of that meeting energised.”

Soon, Dantewadia received a grant of ₹5 crore over three years, and his association with the donor continues to date. Reap Benefit, he says, has today built a community of over 50,000 people [who he calls ‘Solve Ninjas’], who have taken over 94,000 civic actions, started 3,143 campaigns, and built 552 civic innovations to address local civic issues across the country. This involves mapping water-logging during floods, providing urgent Covid relief to over 1.6 million people, executing campaigns to improve sanitation in government schools, and collaborating with government officials in budgeting for and solving municipal issues.

“We are now able to establish the connection between the work done by individual citizens and the systemic impact it creates,” Dantewadia says. The donor’s accessibility and support over the years, he says, helped him build a more resilient organisation. “That is important in philanthropy, because otherwise, philanthropists come with a worldview and push people on the ground to subscribe to that worldview. Here, it was almost like she was subscribing to our worldview and helping us have more confidence in that.”

Rohini Nilekani invests in people, not projects. Perhaps that is her biggest strength. Or perhaps it is the fact that while currently supporting close to 80 civil society organisations—in sectors as diverse as access to justice, climate change, gender equity, independent media, governance and animal welfare—she is keen to learn from each one of them.

In 2020-21, she donated about ₹70 crore in her personal capacity, up from ₹58-odd crore the previous year, as per data on the Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies website. The Edelgive-Hurun India Philanthropy List 2021 calls her “India’s most generous woman”, also noting that in 2017, she and husband Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of IT services major Infosys, signed the Giving Pledge, committing to donate half their wealth toward philanthropy.

Nilekani says while Nandan and she together work at the societal level by investing in intellectual infrastructure and institution-building, her philanthropy at the grassroots involves supporting people trying to solve problems in their own contexts. In 2022, this will involve opening up to new areas like mental health and solid waste management, which require “pan-India deep work”, she says.

Understated profile, oversized impact

Nilekani, 62, believes she just got lucky coming into wealth. An investment of ₹10,000 of her money [partly from her savings and partly given to her by her parents] in Infosys when it was set up in 1981 resulted in her becoming wealthy alongside Nandan, as well as independently of him. Her investments have been separate from those of her husband’s, and therefore, it is her personal wealth that she gives away. In 2005, when Infosys issued American Depository Receipts, Nilekani got ₹100 crore, and decided to create a corpus with the entire amount—along with another ₹50 crore later—for Arghyam, a non-profit she co-founded, to work on sustainable water and sanitation solutions.

She also co-founded Pratham Books to democratise reading for children and served as founder-chairperson between 2004 and 2014. Along with Nandan and Shankar Maruwada, in 2015 she set up the EkStep Foundation, which uses technology to help vulnerable children access education and learning opportunities. She was just experimenting and working on her own in the early days, Nilekani says, before building institutions, deciding to get more strategic and setting up teams. “This way I could focus on strategy and direction, instead of day-to-day management.”

Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP), at present, is a three-person team that is expanding. “That is small for a philanthropy, but the only reason it works is because of the value system, which Rohini not just preaches, but also practises,” says Gautan John, director of strategy at RNP. Allocation of money is the easy part, he says, but the process of building a portfolio with their early-stage funding to individuals and institutions is where the effort lies.

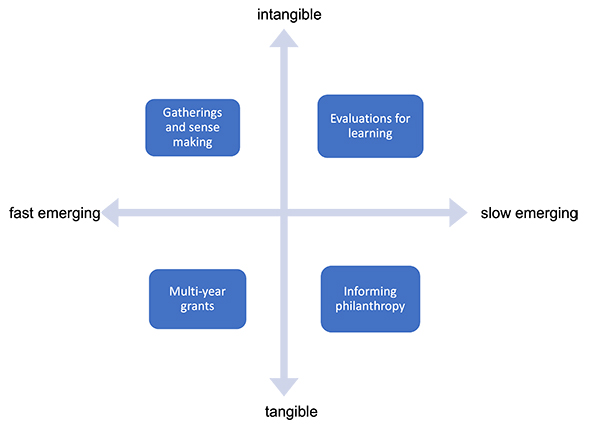

Nilekani and the team spend a lot of time getting to know individuals, their teams and their approach in order to assess if they are able to think about a problem, and its underlying reasons, holistically. Rohini loves to travel and meet people, John says. “And when she is on the field, what she is doing is listening very deeply.” This helps her garner visceral insights about the work that is necessary, and what is absent. Then the team builds a portfolio around it. In each portfolio, RNP has a clutch of people and initiatives that work on the same problem, but have slightly different approaches.

Current and past grantees under Accountability and Transparency, for instance, include Civis, a non-profit platform that facilitates dialogue between the government and citizens on draft laws and policies before they are passed. There is Haiyaa that runs grassroots campaigns to strengthen democracy, governance and human rights, and PRS Legislative Research, an independent research institute. John explains that RNP supports grantees with capacity building, makes connections for them and exposes them to new ideas and thinking. “This way, the portfolio becomes a powerful way to build scale,” he says.

Nilekani has the ability to take risks, and back unconventional causes when many would rather be in their comfort zones. “Indian philanthropists need to become bolder, lead with trust, and look for new areas to fund,” she says. “There are a thousand things that need philanthropic capital to come into.”

Take, for instance, her support over the years to independent media outlets like Vaaka Podcasts, Khabar Lahariya, the Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation, India Development Review and Oorvani Foundation. The business model of media in India is a “little broken”, Nilekani says, and therefore such efforts deserve philanthropic support. Another example is the Access to Justice portfolio, which supports organisations working on a range of approaches to make the legal system fair, equitable and accessible.

“Law is still not treated as other sectors like health care, education or finance where innovation and entrepreneurship have a greater place,” says Sachin Malhan, co-founder of Agami, a non-profit that works to make law and justice more accessible through initiatives for online dispute resolution, digital courts, creating open legal datasets, and bringing together young change-makers for justice. He has received a grant of around ₹8 crore from Nilekani. “Rohini doesn’t come from any fixed script. She does not have some kind of long history of funding only one kind of cause. She funds a diverse spectrum so she knows there are very different ways of getting things done,” Malhan says.

The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment (FCRA) Bill, 2020, tightened the noose around civil society organisations, with provisions that prohibit ‘re-granting’ or the transfer of foreign funds from one organisation to another, and reduce the cap on FCRA funds for administrative purposes to 20 percent [from 50 percent earlier], among other changes. “I feel really sad, because you should not cap administrative costs. Can a company run without all its departments? Of course not. Nor can NGOs,” says Nilekani. “So we need to have much more flexibility and freedom on whether an organisaton spends 15 percent on its overheads or 30 percent, depending on the work done.”

Nilekani says there needs to be more dialogue between government and civil society to reduce prevalent mistrust. “Civil society and the state are in tension everywhere, but it should be a creative tension. It cannot be a climate of fear or so much distrust. We have some fairly draconian laws on our books and you are seeing how they are being used,” she says. After all, Nilekani adds, everyone is working toward the same goal of a better society, albeit walking on different pathways. “That doesn’t mean we can disrespect the other person’s pathway.” And that is the reason she dedicates a lot of effort and money to build capacity to scale, and develop leadership in organisations.

It is Nilekani’s funding toward building capacity that has been the driving force of the India Climate Collaborative (ICC), says acting CEO Shloka Nath. “The crux of the support is that it has been flexible institutional funding that many domestic philanthropists are hesitant to give. They prefer to fund clearly defined programmes that can be tangibly understood, which is why Rohini’s support has been critical, especially given the limits of foreign funding in India.”

Nilekani is also one of the founding members of the ICC, which works to build the capacity of both domestic donors and foundations to support climate action in India, and support efforts to plug gaps in the ecosystem. As per their 2021 annual report, the non-profit has mobilised ₹45 crore since its launch in 2020. “The RNP team has really challenged us—Rohini specifically—to grow, explore and question, while still assuring us of their support,” says Nath. “We found her and her team to be very vibrant, very curious. They really look to learn from their grantees and share their learning with us as well.”

John agrees that Rohini bypasses the power balance between donor and grantees, and insists on learning from the organisations RNP collaborates with. “She says the act of giving should not just change the recipient, but the giver as well.”

One of the things she has also done over the years is to get a lot more Indians interested in philanthropy. “It is important to pick up the phone and get someone excited about what you are doing,” Nilekani says. She believes the indiscriminate accumulation of wealth makes no sense in a society as iniquitous as ours, and that the wealthy owe it to society to be transparent about what they are doing with their wealth.

Social problems do not just go away, Nilekani says, and so there is no end point to philanthropy. “Which is why some people find philanthropy so frustrating, right? That you do so much and still nothing is happening. Yes, it can be frustrating, but it is also a very stimulating and humbling journey.”