IDR | What does the DPDP Act mean for philanthropy in India?

Written by Gautam John, CEO of Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

The Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act of 2023 marks a significant shift in India’s legislative landscape. By establishing a comprehensive national framework for processing personal data, it replaces the previously limited data protection regime under the Information Technology Act, 2000.

The DPDP Act applies to the processing of digital personal data within India, and to data collected outside India if one is offering goods or services to Indian residents. The act encapsulates various principles of data protection, such as purpose limitation, data minimisation, storage limitation, and accountability. It also provides multiple data subject1 rights (rights of individuals whose data is being collected), including access, data correction, deletion, and grievance redressal.

Beyond its legal ramifications, however, the passage of the DPDP Act calls for a moment of introspection for the philanthropic community. The act’s emphasis on data protection and privacy rights is a timely reminder of the evolving responsibilities and challenges faced by philanthropic organisations and their grantees.

While the DPDP Act covers a broad spectrum of data concerns, this article focuses on exploring its implications on impact measurement within the philanthropic realm. As we delve into this facet, it’s worth noting that the act, like any evolving legislation, will invite further interpretations.

CSR’s focus on data-driven impact measurement

India’s CSR regulations have historically pushed companies towards a data-driven approach to demonstrate their social and environmental impact, insisting on detailed tracking of both user data and impact measurement. This is regardless of the model adopted by CSRs, that is, whether they run their own social and environmental projects or allocate grants to nonprofits to execute initiatives on their behalf.

The rigorous demand for data and impact evidence is now at odds with the stringent provisions of the DPDP Act.

For instance, if a company undertakes an education initiative directly, it might require detailed student profiles to demonstrate the tangible outcomes of its interventions. In a similar vein, nonprofits being funded by companies are often asked to furnish comprehensive reports showcasing impact—this necessitates the collection of data such as medical histories, personal narratives, or academic progress, depending on the project.

This rigorous demand for data and impact evidence (in both approaches) is now at odds with the stringent provisions of the DPDP Act, especially those pertaining to user data collection, storage, and reporting.2 Such a clash has significant implications for funders and civil society organisations that engage in impact measurement and evaluation, and raises important questions about user data collection and reporting and compliance.

What will change?

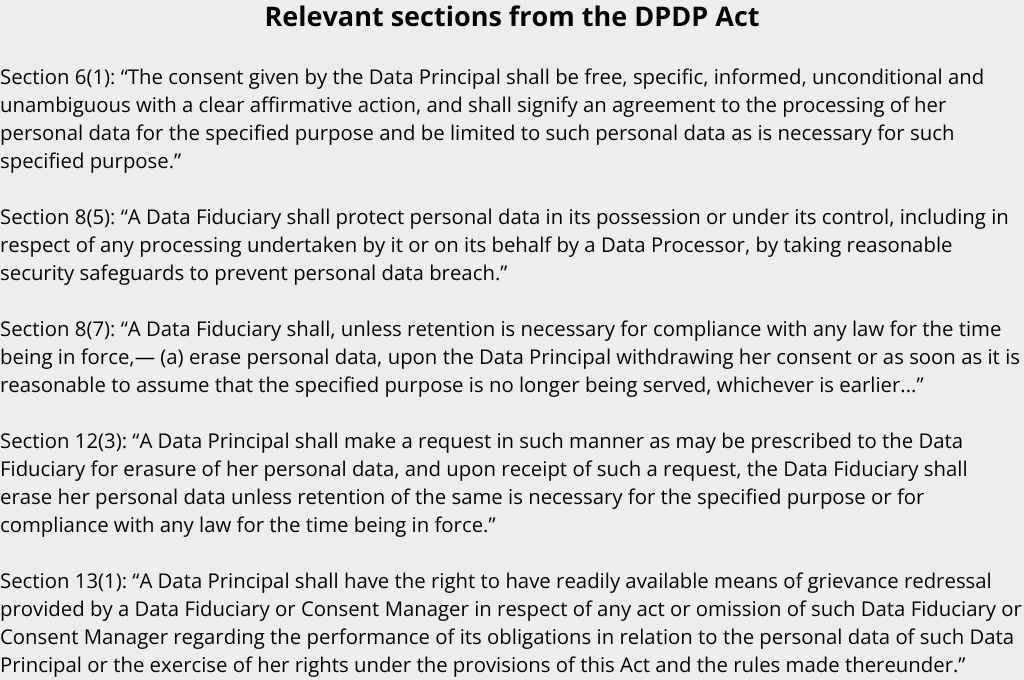

Collecting personal details without informed consent was an ethical conundrum even before the introduction of the DPDP Act.3 The act merely crystallises these ethical concerns into tangible legal mandates. For example, under Sections 3 and 4 of the new legislation, gathering intimate personal information such as health records or financial data without explicit consent could pose legal risks.

Moreover, the act’s emphasis on data security, minimisation, and explicit consent complicates the previously straightforward reporting processes integral to CSR. Complying with data security and minimisation requirements in Sections 8 and 11 may add substantial administrative burdens for resource-strapped organisations.

In addition, if nonprofits are to comply, they will be confronted with increased legal liabilities and administrative overheads. This cost is more than just financial; it takes away from resources that could be channelled into doing transformative work.

Going beyond numbers

Given the stringent requirements of the DPDP Act, there’s a pressing need for revisiting and potentially revising the CSR guidelines. Striking a balance between accountability and privacy becomes crucial in ensuring compliance with both CSR and data protection mandates.

While accountability remains paramount, it’s time to transition from rigid metrics to narratives of change. By fostering relationships built on mutual respect and shared learning, practices followed by donor organisations can resonate with the ethos of the DPDP Act and nurture a more collaborative philanthropic ecosystem.

This necessitates a fundamental rethinking of how social impact can be measured, and shifting the focus from data collection to storytelling and community empowerment. By upholding privacy and agency, as per Sections 6 and 12, the law provides an opening to develop more participatory and human-centred evaluation frameworks. Funders are pivotal in enabling this evolution by modifying expectations, building capacity, and championing new trust-based and collaborative models of assessing progress.

While the philanthropic sector, especially CSR, has traditionally leaned heavily on quantitative metrics to measure impact, it’s becoming increasingly evident that numbers alone don’t capture the full spectrum of change. Trust-based philanthropy does not seek to abandon these metrics but to complement them. It suggests that, alongside traditional measurements, there’s room for more qualitative, human-centric indicators.

Drawing from the experiences of pioneering funders and nonprofits, here are our learnings on implementing trust-based philanthropy in the context of the DPDP Act.

1. Have conversations with your grantees

Funders have an obligation to understand impact, but the understanding becomes more profound when it’s rooted in both data as well as human experiences. Strict numerical metrics sometimes miss the nuanced changes and adaptations taking place in communities.

Instead of solely focusing on end results, trust-based philanthropy encourages funders to appreciate the journey—the collaborative learning processes, the stories of resilience, and the community-led innovations that are responsible for those results. This doesn’t mean throwing away the numbers, but instead adding layers of narratives and community feedback to them.

Rooted in values such as equity, community, and opportunity, trust-based philanthropy aims to build stronger relationships with grantees, cultivate mutual learning, centre trust with nonprofits, and redistribute power in the philanthropic sector.

Funders can start by initiating conversations with grantees about their experiences and stories on the ground. Impact assessment can become a richer, more holistic process by incorporating tools such as participatory storytelling and feedback loops. The idea is to strive for a balance between quantitative outcomes and qualitative process learnings.

Trust-based philanthropy envisions a future where impact measurement is not only about hitting targets but also about understanding the depth and breadth of change—change that is driven by people and their stories, and supported by numbers, not dictated by them.

2. Streamline data demands

By streamlining data demands, trust-based philanthropy liberates grantee partners from the complexities of data management and aligns seamlessly with the DPDP Act. The implications of excessive data collection extend beyond administrative burdens. Constant monitoring can feel invasive to communities and reduce their rich life experiences to mere data points. Such scrutiny can be emotionally taxing and may alienate the very individuals we aim to uplift.

Trust-based philanthropy inherently champions data minimisation and privacy—both of which the DPDP Act emphasises—by valuing qualitative insights over exhaustive quantitative data.

From an economic perspective, trust-based philanthropy offers undeniable benefits. By minimising costs related to data collection and compliance, funds can be redirected to more impactful initiatives, optimising the societal value of every rupee invested.

A compass for CSR and philanthropy

Recent research provides mounting evidence that trust-based practices are taking hold in philanthropy. A 2023 CEP study found that more than half of the nonprofit leaders surveyed reported increased trust from funders compared to the previous year. Many nonprofits also experienced shifts towards alignment with trust-based tenets, including 48 percent seeing reduced grant restrictions, 40 percent receiving more multi-year funding, and more than 50 percent facing streamlined applications and reporting. Nonprofit leaders specifically cited unrestricted and multi-year funding as the most helpful changes. This demonstrates the growing embrace of flexibility, responsiveness, and mutual understanding.

The DPDP Act should serve as a compass for CSRs and the philanthropic community. By moderating our data demands, we uphold the privacy and agency of the people we serve and alleviate the burdens on our grantee partners.

As we stand at this crossroads, we envision a future where Indian philanthropy is celebrated for both its generosity as well as its trustworthiness. This is an opportunity to champion philanthropy that’s not just compliant with the law but also resonates with the communities

—

Footnotes:

- The terminology used in the DPDP Act is ‘data principal’ for the person to whom the data relates and ‘data fiduciary’ for the processor of the data. This is intended to recast the provider as the primary owner and rights holder (as the principal) and implies fiduciary duties on the data processor (to ensure that processing remains in the interest of the data principal).

- It should be noted that Section 7(d) of the DPDP Act allows for the processing of personal information used in reporting required by the State.

- The requirement of active and affirmative consent for sensitive personal data (health records and financial data) was already a feature of the IT Rules. With the DPDP Act, there has been some easing of norms—while informed consent is the norm, Section 7 allows a data fiduciary to proceed with processing personal information that the user provides voluntarily and for a specific purpose. This is in the spirit of opting out rather than in. However, providing notice and opportunity to exercise rights (access, correction, and erasure) are required even in non-consensual processing, and so there will be administrative overheads to ensure compliance.

Keywords

You may also want to read

The Philanthropist | A Joyful Responsibility: Rohini Nilekani’s Philanthropic Journey through White Spaces and Hopeful Futures

Rohini Nilekani did not arrive at her philanthropy with answers, but with questions. There is a particular kind of discipline in journalism: the discipline of not knowing. “You’re trained in[...]

The Indian Express | We Need a Mental Health Movement Rooted in Community

When we help others, we help ourselves. It is a win-win described for samaaj by good science Just five minutes a day of contemplative practices to improve mindfulness, connection, insight[...]

IDR | Is Data Failing Us?

By Natasha Joshi, Chief Strategy Officer, Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies Last year, we at Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies interviewed 14 social sector leaders and funders to inquire what they thought were the biggest issues[...]