E11

Prof Madhav Gadgil: We must work with the people to protect nature

In this episode of Grassroots Nation, Professor Madhav Gadgil speaks of his extensive research in the Western Ghats, the influence of Marathi poetry on his approach to difficult situations and his prolific writing in English and Marathi. He was awarded the Padma Shri in 1981 and the Padma Bhushan in 2006. In 2023, he published his autobiography, A Walk Up the Hill in multiple Indian languages.

Professor Madhav Gadgil is in conversation with Professor Gurudas Nulkar, the director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics in Pune. Professor Nulkar is a well known ecologist and academic. This interview was recorded at Professor Gadgil’s residence in Pune.

Subscribe to Grassroots Nation: Spotify and Apple Podcast

Speakers

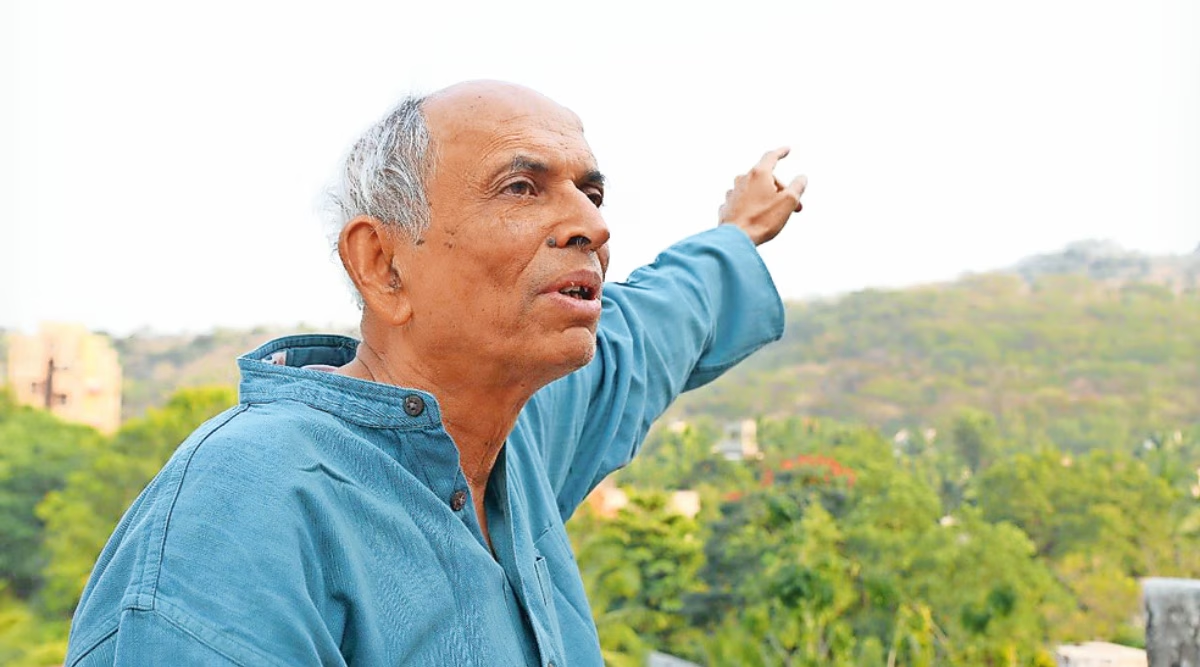

Dr Madhav Gadgil

Professor Madhav Dhananjaya Gadgil is one of India’s most prolific and well known ecologists. He was born in 1942 into an illustrious family – his father, Dhananjaya Gadgil was an Indian statesman and economist who put together the Gadgil formula. From an early age, Madhav Gadgil was interested in nature, a curiosity that was nurtured by his family, and his neighbour, the renowned sociologist Irawati Karve. He cites his early communications with ornithologist Salim Ali and the writings of JBS Haldane as also being early influences.

After obtaining a PhD in Mathematics at Harvard in 1969, Madhav Gadgil returned to India – much unlike the majority of his peers – to build a career here. His contribution to Indian ecology is vast, establishing key research centres, as is his work on environmental policy – he has sat on numerous committees, was a member of the prime minister’s scientific advisory council and more recently, was the Chairperson of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel.

Professor Gadgil is married to the meteorologist Professor Sulochana Gadgil.

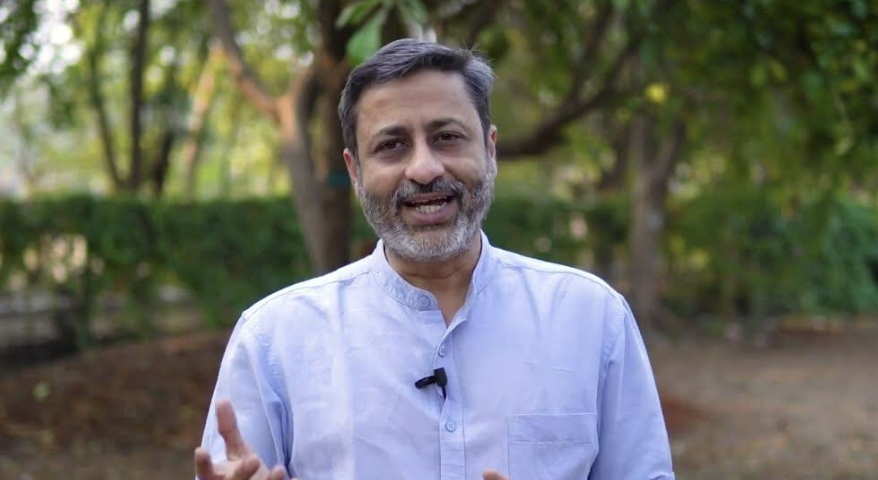

Prof Gurudas Nulkar

Professor Gurudas Nulkar is Professor and Director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune, India.

On the whole what is happening is that nature is being destroyed and people are being deprived of their access to resources to enrich the pockets of a small number of people, which is a serious challenge and this has to be combated. May be, as I said, knowledge and information reaching out to wider group of people. This will be increasingly challenged.

Dr Madhav Gadgil

Audio:

Segment from a news bulletin from NDTV Profit/BQ Live 27 Aug 2018 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EjwWqIh5PN8&t=23s

TRANSCRIPT:

Welcome to Grassroots Nation, a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, a show in which we dive deep into the life, work, and guiding philosophies of some of our country’s greatest leaders of social change.

Professor Madhav Dhananjaya Gadgil is one of India’s most prolific and well known ecologists. He was born in 1942 into an illustrious family – his father, Dhananjaya Gadgil was an economist who put together the Gadgil formula and Indian statesman – a professor and vice chairman of the planning commission of India and a nominated member to the Rajya Sabha. From an early age, Madhav Gadgil was interested in nature, a curiosity that was nurtured by his family, and his neighbour, the renowned sociologist Irawati Karve, and his early communications with ornithologist Salim Ali and the writings of JBS Haldane.

He studied for a PhD in mathematics at Harvard and graduated in 1969, and returned to India – much unlike the majority of his peers – to build a career here. His career and contribution to Indian ecology is vast, establishing key research centres, as is his work on environmental policy – he has sat on numerous committees, been a member of the prime minister’s scientific advisory council and more recently, was the Chairperson of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel. He was awarded the Padma Shri in 1981 and the Padma Bhushan in 2006. In 2023, he published his autobiography, A Walk Up the Hill in multiple Indian languages.

Professor Gadgil is married to the meteorologist Professor Sulochana Gadgil.

Today, Professor Madhav Gadgil is in conversation with Professor Gurudas Nulkar, the director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics in Pune. Professor Nulkar is a well known ecologist and academic.

This interview was recorded at Professor Gadgil’s residence in Pune.

NULKAR

Good evening, Professor Gadgil. It’s my privilege to have this conversation with you to get to know your journey, the challenges you overcame and the peaks that you climbed in on this eventful journey. You have spent much of your career at the Centre for Ecological Studies at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. You have taught at Stanford, Harvard and some of the top most universities of the world. Your work has taken you from the mountains in Arizona Art to the Caribbean coral reefs, from Africa to the trip you made to Kodagu as a school boy but you have often said that your love lies in the Western Ghats, the mountain range parallel to the western coastline of India. You’ve enjoyed working in these mountains, documenting life forms, staying with the local communities and enjoying their food. And all of this after spending years at Harvard University, rubbing shoulders with eminent scientists and accessing some of the world’s best laboratories. Which brings me to my first question. What got you started in your journey of change? Was there a specific instance or instance in your childhood or any influences that hooked you to the life of scientific exploration?

GADGIL

Well, I guess my father was an economist, but he was very interested in natural history and all disciplines of knowledge really. And he was an enthusiastic bird watcher and very good friend of Salim Ali, the famous ornithologist and from a young age I was identifying birds looking at pictures in Salim Ali’s book of Indian birds well before actually I could read. In those days we were not forced to go to schools and start reading, learning to read and all very early. So by the age of 5 years and you know reading or writing, but at that time I was already recognising birds. It was fun. And then when I was fourteen or so I had a question about this bird green beater and how it loses its spin feathers from the tail in certain seasons. And there were no answers in any of the books and my father said, why don’t you write to Salim Ali and ask him?

So I wrote to him and very promptly – he had a very elegant handwriting – he replied within 3 days that at the time of the moult the feather is shed, the spin feather, only later it will start, so you wait for another month and a half, it will sprout. So I was really amazed that you know he took that trouble and explained and indeed the spin feather resprouted in one month or so. So there were these baya weaver birds. So Salim Ali was very interested in the breeding biology of baya weaver birds. He was the man who elucidated this complex behaviour and near Parvati hills in Pune station where there is this canal and bubble trees along the bank. He used to come to observe the baya weaver bird colonies. So next time I was 14 and he came to Pune, I went, I made an appointment, I went and talked to him and his enthusiasm, his wit, and knowledge of birds and all, I really was so charmed that I decided that I will become like him, a field biologist. And I told my father that is what I want to do and my father was very happy…generally my parents were putting pressure…you know you go to engineering college at this and that and I could have easily done so. I had no problems in terms of doing well in exams, but my father said if that’s what you are enjoying, you do that. So that’s how I turn to field ecology and then since we are so close to the Western Ghats, in fact the spurs of the Western Ghats, you will see all over here the all these hill ranges. And my father was very fond of trekking and both on the Western Ghat proper but on these hills, so I became very fond of these.

There were also very interesting descriptions in the literature which stimulated my thinking. There is this history of Marathas written by Grant Duff. He was an East India Company officer and he writes of how the whole Western Ghats were completely tree covered. And by this time you saw, you know, a lot of it had been destroyed. So I was wondering now how did it become so treeless if we in 1829 or so he is describing it. It was so verdant within 150 years, 130 years at that time, how had it become largely treeless in many parts. And there is a very interesting book Jyotiba Phule, you know, he is a great social reformer and I was attracted to his writings and he has described how to him and I think that was historical fact very clearly it was the drain of these forests by the British using the tool of forest department that had destroyed all this tree cover. So I began to think about, you know, these kind of issues also and then simultaneously my father was very much interested in cooperative movement and in 1949, when I was just 7 year old the first cooperative sugar factory anywhere in the country came up here at Pravaranagar and before that when I was 5-6 years old, I used to go with him, visit there and we would sit actually on the floor with the farmers and have lunch with them and chat with them. So not only did I become very fascinated by the birds and beasts and the forests, but also by the people and their culture, which is, I believe, an unusual combination. Almost all the nature lovers, I am afraid, hate people, but I don’t. I mean, I am very fond of our people and our culture and that is how I think, you know, sort of my whole career was shaped.

NULKAR

This was probably some of the first influences in your life to move towards scientific exploration.

GADGIL

Very briefly now, JBS Haldane was a major figure. JBS Haldane, you might know, was one of the greatest scientists of last century, especially in terms of evolutionary biology, and JBS Haldane in 1956 , in fact, the same year that I was talking about my meeting Salim Ali, he left England, gave up British citizenship and came to India, declaring that British and French and Israeli invasion of Suez was an act of imperialism which he could no longer stomach.

So Haldane migrated and took up Indian citizenship. So he came to the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata and my father was on the governing board and he was involved in inviting Holden to come to Calcutta. So I heard a lot about Haldane and this whole issue of, you know, imperial influences and how they had drained India’s wealth and so on. And I also became very interested in the writings of JBS Holden and he was not one may say there are basically 2 kinds of biology, in a way. One is descriptive biology – other is analytical, looking for causes, effect and so on. Which is to my mind the genuine heart of science. So Salim Ali was wonderful but he was either .. the way which people at Harvard, the students used to kind of dismiss people like Salim Ali saying they are stamp collectors, they are not scientists. Haldane was a not a stamp collector. He was a scientist in the true sense. I mean he had enormous understanding of natural history but he combined it with understanding the processing involved and his books – my father has an incredible collection of books all he believed that writing for the people. So there were lot of popular books he has written and they were in our collection. So I read them and so I became interested in his brand of science. So that is what took me to Harvard.

NULKAR

You also fondly refer to your interactions with the great anthropologist and socialist Iravati Karve and mention how you got to handle anthropological artifacts and conduct research without external funding. Could you tell us a little bit about that part of your life?

GADGIL

So she was our neighbour and her daughter Gauri was the same age as me. Gauri Deshpande later became a well known writer. Anyway, so Gauri and I were just one month apart. And since Iravati Karve’s family was next door, I was spending a lot of time in her house also and she went on paeleontolological explorations with her paleo biological colleagues of Deccan College. And then she would bring back all sorts of things, you know, these quartz needles and bone needles, which the Stone Age men…people used and so on. And she would show them to us. It was fun. Now when I was 9, she was going to spend a month in Kodagu which is you know even today beautiful part of the country, tree clad and with very large wild elephant population. And she asked my mother and father whether I could join them for this month. And since, you know, actually it meant missing school for one full month. So my headmaster said you can’t go. So my father said, you don’t worry, he will learn quite a lot while he is there with her and we will take care of his studies. So I went and there she was, you know, doing her…one of her interest was anthropometry, body measurements, head measurements and so on so she was actually collecting that data and talking to the people. Of course she didnt know Kannada but I had an uncle who stayed in Belgaum. So he was very good both in Marathi and Kannada. So she had taken him as the interpreter and so with him also I learned Kannada also and little bit but it was seeing research in action now she had always very little funds. She wrote a classic piece of work on kinship terminology in Maharashtrians communities. All the data she collected simply by going on long bus rides on public buses, right? Talking to people and hardly any question apart from buying those bus tickets. So I said well you can do field work and you can do good, re-scientific work intellectual work. You do not need money necessarily.

NULKAR

So here I must inform our audience that Professor Gadgil’s love for Western Ghats is so intense that after he retired he bought a house which is nestled around the spurs of the Western Ghats. So while we do not have the green cover which Grant Duff described in his book, but we are still around the Ghats in your house.

GADGIL

Yes, of course. That was one of the reasons why I really want you want to come here after coming back from Bengaluru.

NULKAR

Your father was a renowned economist in India, Professor Dhananjay Rao Gadgil, and you got to learn a lot of economic thoughts from him. One of the concepts which you have described earlier was the concept of externalised costs of economic development in a country. As an ecological scientist, did this economic thought have any influence on you?

GADGIL

Yes, yes. I mean I was very interested in, you know, the whole range of disciplines as I said, and the Cambridge economist who was the originator of the idea of externalities and so on was Pigou and Pigou was my father’s thesis guide.

NULKAR

Arthur Cecil Pigou.

GADGIL

Arthur Cecil Pigou. He was my fathers guide for his MPhil thesis at Cambridge and we had writings of Pigou and so on at home also and we would discuss these… I had a very interesting experience when I was 14, again, there were this series of notable instances …Koyna Hydroelectric dam was under construction.

NULKAR

In Maharashtra.

GADGIL

In Maharashtra and my father in the Western Ghats, in fact, my father was member of some Commission, Irrigation Commission, I think, of Maharashtra government and they had a meeting there. So he used to enjoy taking me with me and I…he took me along for this meeting and as we drove we saw amongst other things that many large areas of forests were unnecessarily destroyed and my father was very sensitive to the fact which is learnt while the whole discussion and understanding of the project was being communicated through these meetings, that they were given no proper rehabilitation, no compensation and great injustice was done to them. So at the end of the day he was very distraught … generally he was a happy man. And he would talk to me about this, that, you know, we of course need to produce electricity for our industrial progress, but to incur this undue costs of destruction of nature and impoverishment of people is all wrong. And in fact he told me a bit about what Pigou’s ideas were at that how social inequality actually depresses the total welfare of the society and so on. And so, yes, so even the at that age I was influenced by these ideas.

NULKAR

And there is quantitative proof towards that.

GADGIL

Yes, yes, yes, plenty.

NULKAR

Professor Gadgil, you have recently published your autobiography, and I believe this would be the first time that an autobiography is being released simultaneously in 9 languages. Just a while ago, you mentioned about the incident with your father and the sugar cooperative factory. And you have written in that book that your father was on the board of the sugar factory in Maharashtra and he wanted you to translate the annual report into Marathi so that the farmers would be able to read and understand that. Would you say that this incident has some influence on your translating the autobiography into nine languages?

GADGIL

That I cannot say but I actually at that time lot of people from their upper classes were educated in Marathi and like today when most of them go to English schools or even the Marathi schools have become largely English language schools. So I learned Marathi right through and I was very fond of Marathi literature and especially Marathi poetry and yes, that time it was the first time I wrote something in Marathi seriously. But then I when I was … a little, later, a year later or so, there was this Popular Science magazine Shrishti Gyan. It still runs though that time I think it was in its heyday. I wrote some articles on birds and so on for Srishti Gyan at the …due to the encouragement of actually Iravati Karve who was on the editorial board.

So I had from that time started. I was interested and I wrote popular articles on science from the age of 15 or so regularly and I continued to. It is part of my interest in writing, but because of my interest in all parts of the country and actually some programs I undertook of decentralised monitoring involving number of partners and networks of people that has provided me good friends from essentially every part of the country and when I started writing the autobiography they said they want to translate this way quite spontaneously. So that is how it has got done.

NULKAR

But I remember you also insisted that the government published the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report into local languages, which can be read in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Kerala. Unfortunately, the government did not heed to your request…

GADGIL

That was, I mean that was part of a major recommendation of our panel.

NULKAR

Absolutely, which was not considered by the panel. I have seen your library and your books and you have often said in your speeches that you were a voracious reader in as a youth. I have heard you talk about Salim Ali’s books, but also Dharmanand Kosambi, Jyotiba Phule, Aatre’s Gaavgada, Rachel Carson and JBS Hardin and others. How is the love for reading carried through in your career? Has it helped you in any way, or has it helped you build upon your scientific exploration?

GADGIL

I guess, but there are many inspiring actually passages in the poetry. Let me take one specific example. You know, there is this poem by Kusumagraj about the soldiers – I mean the senior, the general, since Shivaji’s army actually running away in a war with the Mughals and he condemns them and they say that, well, it was something we did, which is not what a Maratha should do. You should never run away from any flight. I was a boy. I read that poem, but I read it again and again.

Vedat marathe veer daudate saat… so if there is a controversy, I enjoy controversy. And if there is pressure to ignore and yield, I say no, no, this is not the way. So the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report was attacked by …viciously actually by misquoting this information of various sorts being promulgated…and there were friends who said arre why you bothered? I said no, no, that is I have written it for the people of India and not for any governments who are may be completely ruled by vested interests,so I will go fight. So I have continued, and many, many other ways, but sometimes came up such controversies and if I felt that I was right, I never yielded.

NULKAR

So from Ferguson College and Institute of Science to Harvard it has been a very long journey I’m sure and you got to spend time with great scientists like Edward Wilson Guiles Mead. But you also spend time with other scientists like Paul Erlich and Jared Diamond. How would you describe your education beyond your PhD in Harvard?

GADGIL

See, there were very clear interesting lessons. I was actually I would say disgusted by the fact that my teachers in Institute of Science in Mumbai were lazy, they would do nothing, no stitch of work on their own. All they would do is to get their students to …PhD students to write thesis and put their name on this publications.

NULKAR

As co-author.

GADGIL

Co-author without having given any inputs to them students. Harvard was utterly different, you know. And there was also a culture which is very different and mentioned in the book that on the first day I took a course algar chemistry, biochemistry and physiology and after the lab was over we were leaving and I saw the assistant professor had no helpers… he was himself washing the glassware with the students had left. And in India in any lab no faculty is going to ever think about washing the glassware. And so there was a whole different culture. And then there I was also slowly began to appreciate how the European science had employed fundamental sciences to drive technological progress. And of course those technologies were used to dominate the world in trade war and so on. Harvard had been the place where in the computing center the calculations for the atom bomb were done and all sorts of things. And I was attracted to computers and so I learned a lot about history of computers and in general I saw the behaviour of the faculty and easily how they would mix to with the students and very little hierarchy in their relationships.

So all of that you know was tremendous in the sense of cultural experience. Then of course, how actually science should work and the hypothetical deductive method and so on…and how science must have only one basis, which is objective facts, all that kind of thing. I had some understanding of that, but it got consolidated during the Harvard years.

VO

Although he had many offers of professorships at some of the best universities in America, Professor Gadgil and his wife, Professor Sulochana Gadgil returned to pursue their careers in India in 1971. Madhav Gadgil worked at the Agharkar Research Institute in Pune for two years. His explorations of the hills around Pune during this period led to research on sacred groves, seeing them as excellent examples of local, indigenous conservation. He joined the Indian Institute of Science in 1973. He would stay at the IISc for thirty years. His legacy at the IISc is vast – he established both the Center of Theoretical Sciences and the Centre for Ecological Studies.

NULKAR

Both you and your wife, Professor Sulochana Gadgil, were very fortunate to be getting into such a renowned university and having to do PhD with some of the most eminent scientists. After your PhD, both of you were offered prized positions in teaching in Harvard and MIT, and yet you both chose to move back. Was this somewhat contrary to the flow at that time? And what could be the triggers for such a decision for both of you together?

GADGIL

It was contrary entirely because of all the Indian students at Harvard that were with me, there was only one other Suresh Tendulkar, who is a distinguished economist, you know, and he is the brother of Vijay Tendulkar, the great Marathi writer, he came back and I and Sulochana came back, but there were may be seventy others Indians students at Harvard and sixty seven stayed there. So it was certainly against the general tendency.

NULKAR

So what were the… what were the influences? What made you both simultaneously take this decision?

GADGIL

No no, there were basically that both Sulochana also she enjoyed being in India and I very much enjoyed being in India. And so she was agreeable very much to coming back to India

NULKAR

But I’m sure the thought must have crossed your mind that coming back to India, the research rigour in Indian institutions would perhaps much less than an American reputed university, that you were coming from and also that funding for research was not easy to come by in India, did that not influence your decision in any way?

GADGIL

Nahin, nahin… I was interested and I had every intention to do field ecology which would not need much money. As I said with Irawati Karve’s example, we don’t need much money for such work. So the funding was part of that and as far as the rigour and so on was concerned, I wanted to inject it into Indian scientific community if at all possible. And fortunately anywhere I might have vanished but Indian Institute of Science was an institution where this was readily possible. It was led by Satish Dhawan, great technocrat, so it was readily possible there.

NULKAR

So before your stint at the Indian Institute of Science, you joined the Agharkar Research Institute in Pune, where you got to work with your former professor, Professor VD Vartak. You undertook research on sacred Groves or devries as they are called in Maharashtra and where started with the fact that sacred Groves are not even acknowledged by the forest department back then? What were your experiences during this phase in your career at Agharkar Research Institute?

GADGIL

I mean this was the first research I undertook in India.

Now the hypothesis which was being promulgated was that the sacred groves were protected solely because of religious feelings and that as the religious feelings decline they would be destroyed. But I thought that very likely the local community might be protecting them because of some ecosystem services such as protection to water sources. And therefore while collecting the data I deliberately collected data which would answer this kind of a question. Also I saw that the kind of prevalent feeling which Varthak also shared that it is the ignorant self shortsighted villagers which are destroying these sacred groves and there was abundant evidence how how corruption of forest department, irrigation department was actually driving the destruction. So it was a very good learning of the social forces and political economic forces in operation.

NULKAR

In the year 1973, both you and your wife, Professor Sulochana got an opportunity to work at the Indian Institute of Science under the visionary leadership of Professor Satish Dhawan. Here you are involved in setting up the Centre for Theoretical Studies and the Centre for Ecological Sciences, which later became a very eminent center of scientific research. How did you build the CES as it is called, into India’s leading centre for scientific research? We have.

GADGIL

I took full advantage of the matrix of Indian Institute of Science that permitted interdisciplinarity. So on the faculty also as well as with the students, we could have people from all disciplines. So I had students – Sheshagiri who was from a farming family but had a degree in MSc with Agriculture and Prabhakar who had a IIT MTech in the computational biology but he was fascinated by maps and he became my student and he did a very nice thesis or maps as markers of ecological history of Nilgiris. And so you know … whole kind of interdisciplinarity was possible and then the I could inject into this work serious quantitative studies and proper use of you know statistical and other tools. Again it was the Indian Institute of Science which better it possible and as new disciplines took route such as use of remote sensing and ecology very quickly in Indian Institute of Science it was possible because I could. There was an electrical engineering department, remote sensing group but as soon as it started functioning I made friends with the faculty there and maybe this is unusual. I went and attended courses they were teaching on remote sensing. I was maybe at a higher level as a faculty than them, but I sat as a student in those courses and learnt and then later I taught myself. So all this was possible in the Indian Institute of Science, in other universities I don’t think it will be possible.

VO

Professor Gadgil has studied many areas of ecology including work on forests. From 1986 to 1990, he was appointed as a member of the Prime Minister’s Scientific Advisory Council and it was then that he was instrumental in the establishment of India’s first biosphere reserve in the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu.

NULKAR

But perhaps I feel one of the most significant contributions at the Centre for Ecological Sciences was probably the establishment of the first biosphere reserve in the country, which is the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Could you tell us the story behind this achievement and how did you excite the government to get onto the idea of protecting biosphere reserves across…

GADGIL

See, I started out with the prejudices, actually, as I said in the urban society that protection of nature requires exclusion of local people, which was the philosophy that Salim Ali also very strongly advocated and he was my guru and my idol. And I started off with this, but then, as with time went on, and I understood what was going on on the ground, then I came to realise that no, this is not the way. We must work with the people to protect nature and with the people to protect nature.

And there was a program of the UNESCO called Biosphere Reserve which talked about this approach, protecting nature as part of joint endeavour of the communities and the governmental apparatus. So I was attracted to this idea. Now luckily at that time the person who was calling for proposals to be submitted by the Indian government to UNESCO for biosphere reserves was BP Pal.

VO

Benjamin Peary Pal was an Indian agronomist who was the director of the Indian Agricultural Institute and the first director of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

GADGIL

Now BP Pal was a remarkable man. I must tell you stories of what he was. His name was Benjamin Peary Paul. He was in fact the first Director General of Indian Council of Agricultural Research and very fine agricultural scientist. Anyway, he was also a great artist in his house. He had these paintings of incidences of Draupadi’s life in Mahabharata and he had a wonderful aesthetic sense that he had roses and bougainvillea apart from wheat varieties which he bred, red roses and bougainvillea. Anyway so this man was in charge of this program and we became good friends and he encouraged me and so I got to submit the Nilgiri biosphere reserve proposal. There were hurdles because it involves three states coming together and bureaucracy working with people which is anathema to them. So it took some time, but yes it did in the end become the country’s first biosphere is right…

NULKAR

And after that, the government went on to conserve several other biosphere reserves. In one place you mentioned about ecological prudence, which I think is very important for our audience to understand. Which ecological prudence which is demonstrated by especially tribal communities and hunting gathering communities and also the fisherfolk of North Karnataka with whom you worked in your research. But with the fisherfolk of North Karnataka, you mentioned the use of a precautionary principle that led to sustainable fish populations. Can you expound on this and tell us what has led to the decline and ecological prudence today?

GADGIL

No okay okay. See ecological prudence is taking long term consequences in view and using ecological resources and commodities which had control over their resource base. They tended to throughout history. You have many examples of ecological prudence, not just in India but other parts of the world of communities which control their ecology resources, of a practicing ecological prudence. The fisherfolk, actually it is not so much North Karnataka, I was working in Mumbai and in Mumbai that time the Japanese had introduced trawling for the first time. So there was this trawler which the Japanese were using to train the fishermen to use trawlers. I was interested and so I went on some trips on this trawler and I was … as is my wont I had immediately contacted the secretary of the Mumbai Maharashtra actually Fisherman’s Cooperative Union and I got to know the fisherfolk also and they were told me that look trawling would bring more fish catch to begin with but it will certainly in the long run deplete because this trawler the way it drags on the sea bottom, will harm fish breeding and in the long run this will destroy…so this is called precautionary principle these days. So they were advocating that and later it has actually come to the fact that this is very well understood, that it is this intensive trawling and fish stocks have been very seriously depleted.

NULKAR

So looking at your work at the Centre for Ecological Studies at Indian Institute of Science in 1980, Indira Gandhi invited you to be on the committee to plan for the Department of Environment. And I don’t think many people will know this fact that you have your contribution towards the formation of what is today called as the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. MOEFCC started with Indira Gandhi’s invitation to you and I think BP Pal was also in that and Zafar Fateh Ali and MS Swaminathan, you know, Sundarlal Bahuguna, all of these illustrious people who have done so many things were on this committee. But very interesting is the point that after the formation of this committee, along with Professor Kailash Malhotra, another very renowned sociologist, anthropologist in India, he and you travelled for a couple of months across India, visiting people who were affected by economic development, getting to know their side of the story before you actually sat, put pen to paper to write a plan for that. So can you tell us something about this, these couple of months that you spend travelling in India?

GADGIL

See, at the first meeting of the committee which was chaired by MS Swaminathan, I said that we should actually have inputs from people at the grassroots in terms of what the environmental issues are and how they should be viewed. So they are readily agreed MS Swaminathan and others also ….BP Pal was there. They were very much in sympathy with this and then I invited KC Malhotra who was a student of ecology, Iravati Karve actually and who had great praise for him and we had become friends and we were working together.

Kailash and I we went around. We choose various regimes, so Goa to understand the mining issues, to understand ocean pollution that was affecting fishing, other trawling and fisheries depletion, then the Rajasthan where we looked at the Bishnoi community but also at various other influences there right at the edge of the desert in Jaisalmer and so on. Then with Sundarlal Bahuguna in Garwal and there was a this very interesting movement about impacts of Tawa Dam irrigation projects in near Hoshangabad. So there and then in Ahmedabad and Pune district.

NULKAR

Vadnagar also.

GADGIL

I think sorry about that I said by mistake Ahmednagar and Pune district.. so that was fun you know, Kailash and I, you know, we were always willing to go around if it is necessary on bikes, bicycles, I mean, not motor bikes. And in several places we saw the people were scandalised that these supposedly senior academics were quite willing to get on to their bikes at Go and we did !

NULKAR

Yeah, one thing I forgot to mention to our audience is as a youth you were also very athletic – you participated in events for represented Pune University, so I’m sure the motorcycle riding love for that must be coming somewhere from your sports part…

GADGIL

I was able to undertake it effectively because I was good athlete as I said maybe, actually I held at one time the Maharashtra state under 14 and under 16 high jump records and Pune University high jump record … I was a pretty good athlete. So I was able to – some of the colleagues they when I was writing this autobiography – One of them was Devi Prasad from Sulia in Dakshin Kannada and he said he remembers that he which was part of our decentralised monitoring kind of network, he and his students came to Tamhini Ghat, you know here, these hills here nearby and we were walking and he said you rapidly climbed up and calmly you were waiting for us to follow and all of us, we were much younger than you were. I was 40 also, but younger than you were but we came up panting several minutes afterwards! So yes I was therefore able to, you know, do all these things because of my love for sports and exercise.

NULKAR

And not just that. I remember on one of our field visits with you, you are very keen to eat local misals and vada pao on the way. So love for trekking and you know your enjoyment of local cuisine is something which is very much specific…

VO

Professor Gadgil’s work in policy continued throughout his career and he has been a member of many taskforces, committees and councils. In 2010, he was asked by the Indian government to chair an expert panel to assess the status of the ecology of the western ghats and identify ecologically sensitive zones as per the Environment Protection Act, and through a consultative process, to recommend pathways for the conservation of this important region. The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel that became known as the Gadgil committee, submitted its recommendations – commonly known as the Gadgil report in 2011 but they were rejected by the concerned states as this issue became highly politicized.

NULKAR

So coming to one of the most important parts of this conversation. As the head of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, you and your team spent a significant time on field work and meeting local people, officials, government officials. But what is also not known is that you employed novel ways of gathering data. So, for example, you held essay competitions for school children in the Western Ghats to understand what is their idea of their neighbourhood and their landscape. You also studied human interventions and their impacts in great detail and poured over scientific studies in the Sahyadri Mountains. The report was hotly debated in Indian politics as well as media. Can you take us through this journey a little bit for our audiences?

GADGIL

Haan, I mean, when, of course, I had been doing studies on the Western Ghats well before I was asked to chair this committee in 2010. As I said from 2019, 73 actually was 71 when I return from Harvard

NULKAR

From Agharkar

GADGIL

I had been engaged in their studies on the Western Ghats. So there was this background, but for the panel there I thought that we must very systematically connect data at the ground level, talk to people, collect data at the ground level, also use remote sensing imagery and so on very carefully. And I, as I said in the Indian Institute of Science I had learnt and I had students who were good at that. So they helped. So with that and actual dialogue with people at the ground level, a very kind of rich database could be put together. And this as I said, we wrote frankly – fortunately the way Jairam Ramesh was the Minister – and he was perfectly happy with honest frank writing of the report. So I could put in the report many things which were unpalatable to the powers that be. For example in Mahabaleshwar, which was much earlier declared an ecologically sensitive area under another piece of legislation, the local people told me that this is used only to harass us, that if we have to dig a well, we are told that no, no, this is ecologically sensitive area, You cannot dig a well. Well, but the ecological sensitivity vanishes when you give them ₹20,000 bribe. I said, you look, I cannot write in the report such things just because you tell me. Will you give me in writing, they said, why not? And actually some panchayat members of Mahabaleshwar panchayat and other citizens wrote to me , wrote a letter and signed with their names and addresses giving this fact. So I have put it in my report. I had very concrete evidence.

VO

Here is an excerpt from a news bulletin following the floods in Kerala in 2018, from the news channel NDTV Profit:

NEWS CLIP

A 2011 report by ecologist Madhav Gadgil is back in the news after the devastating floods in Kerala. The over 500 pages report submitted by the Gadgil committee recommended a slew of measures to preserve the ecology of the western ghats including districts in Kerala some of which have been the worst hit in this deluge. This report was never implemented, and there is now a narrative that the devastation of Kerala could have been less if some of these measures had been taken. To speak more on this we are joined by Madhav Gadgil…

GADGIL

Of such things of course the ruling classes cannot stomach so there was this whole lot of controversy. But I said I must stand my ground, so I never stopped talking about it. And since I had enjoyed writing, popular writing also, I was very sought after actually as a writer in media. And so I have kept writing about this, both in English and in Marathi, So I kept a kind of stream of putting forth my position despite all the campaign which was mounted against our report which has helped because by now, you know the other day in Maharashtra, then there was this horrific landslide in Isharlwadi …the Legislative Assembly… I think leader of the opposition asked the government, what are you doing about the Madhav Gadgil report ? Although it should not be called Madhav Gadgil report. After all, we were a panel. Anyway, but that is how it has come to be called. And so there was some debate. So they are talking about it 10 years after it was disclosed and 12 years after it was written and everywhere there is been a awareness developed and I’m happy about that.

NULKAR

Yeah, I think its very important even today to bring up that report and get any discussion. From your first book which gained international recognition. This Fissured Land, which is the book I read very long ago and in all my classes I put that as a recommended text reading, although it’s not at all an academic text. So from The Fissured Land which you wrote with Ramchandra Guha till A Walk Up The Hill, which is your recent autobiography, you have been a very prolific writer. And not just in English, but in Marathi, where you have been writing columns in local newspapers as well as magazines and across international magazines. I think very few scientists or academicians connect with civil society at large through a mouthpiece which is based on popular science or very easy reading of science, and I think that has helped gain a strong following towards Madhav Gadgil as an ecologist more than anything. Can you tell us a little bit about your experiences as an author? Do you still enjoy writing, or does it come naturally?

GADGIL

See JBS Haldane I mentioned mentioned at the beginning he was, although I never got to meet him personally, nevertheless, he was my idol in many ways, both in terms of serious science as well as in terms of this popular writing, So I always thought that this is very important and I enjoyed writing. So I started writing.Earlier in Shristi Gyan but then there was a hiatus but as soon as I started working on sacred groves, actually interestingly Salim Ali’s cousin Zafar Fateh Ali, he became interested. So he asked me to write about sacred groves an article which then was published in the Illustrated Weekly of India. So in 1971, this was the first popular article in English.

NULKAR

Khushwant Singh was the editor

GADGIL

Khuswant Singh was the editor I got to meet him. Also actually interesting character. Anyway from ‘71 onwards I was writing occasionally in Marathi because then largely I was in Bangalore and I wrote a lot in Deccan Herald and local other Hindu, The Hindu and so on and occasionally in Marathi. But in 2007, where I came back to Pune, I started writing much more regularly in Marathi. Sakal, Loksatta and so on and very interestingly the response as to the English articles and Marathi articles is different. I find actually this book which is now being launched on September 1, of the boys who is going to come and who became a good friend of mine is from a shepherd community. Saurabh Bhatkar and his family actually they still go migrating with their sheep but they decided to educate one of their family. So they sent him to college and he got a degree in Computer science from Chandrapur and then from Tata Institute of Social Service a degree in social service whatever it is. And now he has been admitted for PhD in Edinburgh University … a very bright boy but anyway, it was reading my Marathi articles that he came to specially meet me ! These things and then the reading my Marathi articles all sorts of people, some remote village carpenter community people, sutars, they have written to me . So these Indian language material reaches out to people in a different way and much wider, much more widely than the English language. So that’s why I was very happy when the possibility obviously came up that my autobiography will be translated in various Indian languages.

NULKAR

So looking back at your journey as a change maker, do you see yourself that you have to make some sacrifices in your life, in your personal life?

GADGIL

No, people talk about it, but I I say that no, I have made no sacrifices. For instance, giving up assistant professorship offers from Harvard and Princeton and so on, and coming back and then later also I had a full professorship office at Stanford, I refused. I was not interested. So those to many people are sacrifices to me are not. I have enjoyed myself in the India may be partly because I had the good fortune to work at Indian Institute of Science with its vibrant atmosphere, but otherwise also and then I have had a physical hardship as part of the field work, including having had to being chased by elephants and spend one night all alone in a tree. But when I enjoyed all those things…there is no, no… so I have never made any sacrifices or I have enjoyed everything and I have had a very good life.

NULKAR

I think our audience will enjoy listening to the story…

GADGIL

Okay see Mukurti in the Nilgiris is an area where it is on the edge of the Western Ghats I mean the Nilgiris, there is a sheer cliff down to the Kerala plains. That was an area I was very interested in and it is very rugged terrain. And I went there with a local guide and Narendra Prasad who was my PhD student and who continued, you know we were working together for field work. Now there was a – earlier the British planters used to hunt in those areas. So they had these game huts, the game huts, the game huts were in the forest covered and you could not see them from outside and there they used to go riding on horses and primarily hunt Nilgiri Tar which was you know, favourite game for them. Now we went to this area with Prasad and that local field guide and I. We walked a long distance one day to a game hut and which is a place called Ankit Malai. And then they were tired and they said enough is enough. But I said enough is not enough because if you climb little more I will go to the top of the cliff there and there Ankit Malai and I will have this magnificent view of the sheer drop of some 2000 meters I guess to the Kerala plains.

NULKAR

Escarpment, was it?

GADGIL

Yeah, the whole escarpment. but the western escarpment of the Western Ghats. So I will go up there and you can go to the hut and I will come back. So I was there at the top and it was a magnificent scenery, except just as I reached the top, I was admiring the scenery, the cloud started coming up from below and pretty soon it became completely cloudy, so then I quickly climb down but down there was no question how will I see that hut. It was some distance away, it wasn’t right there and I would never reach there and very rarely do elephant herds stray into that area… they are generally at lower altitudes but that day elephants had strayed into that area and I could hear their trumpeting and they were breaking branches and so on. So here I was, it was getting very dark. No chance of getting back to the hut. And there are these wild elephants around. And wild elephants if you run into them by accident also just with a swish of their trunk you you will go up…

NULKAR

Sweep over your head

GADGIL

your head will be somewhere else from your body. Anyway you will get killed and a lot of people every year get killed by elephants when they blunder into them. So what can they do? So there is only one way to escape them is to find a tree which is tall enough out of reach of the elephants, climb up the tree and spend the night there. And then next morning may be when it is broad daylight, try to make your way back not to the hut, which I had no chance of finding, but to the lodge of the upper Bhavani Irrigation Project which was some 12 kilometres away, I knew. So I decided that that’s the way to do it. So there was this Bhavani River stream. There was a sandy island there. On the middle of that island was a very nice tree, ficus tsjahela… I remember that out of the fig trees, so I climbed up there about 20 feet and earlier it was dark, but then by 2 o’ clock also the moon rose and mist went away. It was a lovely night anyway, and I’m was very fond of tree climbing from my very young age. So the next morning I got down and I before I went up I had made sure that morning I would be confused which direction the project rest house would be. So I had with pebbles, made arrows showing that I must walk work in that direction anyway finally, some three, three and half hours it took to cover those may be a little more those 12 kilometres and I reached the this rest house from the project and Prasad and my student at this local guide. They had already made their way there and they had decided that only thing to do now was to send out a search party for Madhav Gadgil’s dead body and finally I arrived there alive and there was jubilation and…

NULKAR

But losing a renowned scientist would have been a death knell for his career, the person who was supposed to be your guide, so therefore he was so jubilant.

One of the questions which I asked you is, do you see any challenges towards conservation in India?

GADGIL

On the whole what is happening is that nature is being destroyed and people are being deprived of their access to resources to enrich the pockets of a small number of people, which is a serious challenge and this has to be combated. May be, as I said, knowledge and information reaching out to wider group of people. This will be increasingly challenged.

NULKAR

Coming to the last part of this conversation, do you have any hope for conservation of our natural biodiversity or do you see any challenges which we need to surmount?

GADGIL

No, no, there are. There are very good signs of hope in the implementation of this Forest Rights Act. They have community forest rights provision and I have been very actively involved in working with communities and this has not been allowed to be implemented by vested interest all over. But in Gadchiroli district, a fortunate combination of very honest Deputy Commissioner of the district and good local leadership, 1100 village communities have been given these community for this resources and I have been working with them and once they have control over these resources they have reasserted their ecological prudence which had slowly eroded because they had no control over there actions. So we should see in coming years this happening more and more…situation will go on changing and we will progress towards a more equitable, more fair society. So I think these are very interesting possibilities and I’m quite optimistic.

NULKAR

So today there are several organizations as well as many youth who are turning into citizen scientists as well as, you know, formal education and science. And there are many organizations which allow you to work on that. Would you have any message for them? I’m sure they will be inspired by your…?

GADGIL

I don’t know, my message to them is really that please do not have an elitist attitude as I said even my Guru Vartak had that it is the ignorant and improvident villagers who are destroying nature. They are not. I mean it is the resource demands of the cities, which are probably much more responsible for destroying nature, that their rural divides. Simply without any prejudice go out and work with people, and amongst them with an open mind, and you will do far more valuable contributions than otherwise if you have a prejudice view of the different classes of the societies. do not have such a view. That is my message, perhaps.

NULKAR

So Professor Gadgil, thank you so much for spending such a lot of time with us and sitting up and explaining your journey. I’m sure our audiences would have gathered so many new things about that, and at least a few would have had some influence on turning into field scientists like yourself. So thank you again so much.

GADGIL

My pleasure, my pleasure.

VO

Grassroots Nation is a podcast from Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. For more information go to rohini nilekani philanthropies dot org or join the conversation on social media at RNP underscore foundation.

Stay tuned for our next episode

Thank you for listening to Grassroots Nation.