Key Questions

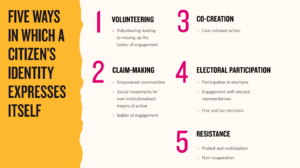

- What are the major interests and online discourse around the four pillars of active citizenship—volunteerism, co-creation, claim-making and resistance & mobilisation in India?

- What are the key influences and impacts of online and offline volunteering?

- Which topics in citizen-led co-creation are dominant on social media, and what platforms are citizens and CSOs using for co-creation quantitatively?

- What kind of structures are created by government institutions for claim-making using social media?

- What is the quantitative reach of online national issues as compared to local issues? And what is the life cycle of hashtags linked with the event of online mobilisation, and do they translate into offline action?

“Citizenship” is most commonly associated with electoral participation, tax jurisdictions, and travel visas. However, citizenship and civic identity is a much deeper experience, where members of society exercise voice, agency and rights in myriad ways to affect change in their localities, cities, States and, indeed, the nation.

Citizens observe things in their neighbourhood that need improvement and often participate/volunteer to make those improvements. Citizens keep track of the promises made to them by their elected representatives and interact with local government to claim their benefits and entitlements. Citizens are employed in civil society organisations where they work alongside the government to help other citizens that are vulnerable or marginalised. And very often, samaaj (which is a collection of citizens) becomes the greatest ally of sarkaar and bazaar as it takes up services from the two and provides dynamic feedback on what is working and what is not.

In order to understand how these identities are expressed in both offline and online spaces, Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, in collaboration with Porticus Foundation, supported a digital ecosystem analysis conducted by QUILT.ai.

The objective of the analysis was to arrive at a clearer picture of how multiple types of civic identities are expressed online – what kind of volunteering opportunities do people look for (online) and how? how do citizens covey their demands at elected representatives or express satisfaction related to civic issues in their locality? How does government communicate with citizens through online platforms, and what issues get the best traction? What are some demographic trends when it comes to civic engagement online?

This report captures the results of some of these queries and improves the resolution of the current image of active citizenship and civic engagement in India.

Key Takeaways

- The shift to online volunteering during the pandemic is reflected in the rise in both searches and social media posts related to volunteering online. The main activities conducted include online classes, tutorials, and workshops.

- Digital co-creation led by citizens indicates three major categories of created content: journalism, awareness & education, and structural reform. Additionally, government institutions use Twitter as a medium to scale up the outreach and adoption of government initiatives and schemes through citizen-led co-creation. CSOs focus more on co-creation-related action for more local issues in the community, such as floods, cleaning, local vaccination drives etc.

- Social media has become one of the leading avenues for citizens to express their grievances online. Claim-making through Twitter was predominantly observed in urban areas as opposed to rural areas.

- Evidence of online mobilisation translating into offline action could be observed on Twitter for the studied events. However, a correlation between the two does not suggest a causal relationship. Further research is recommended to gauge causation.